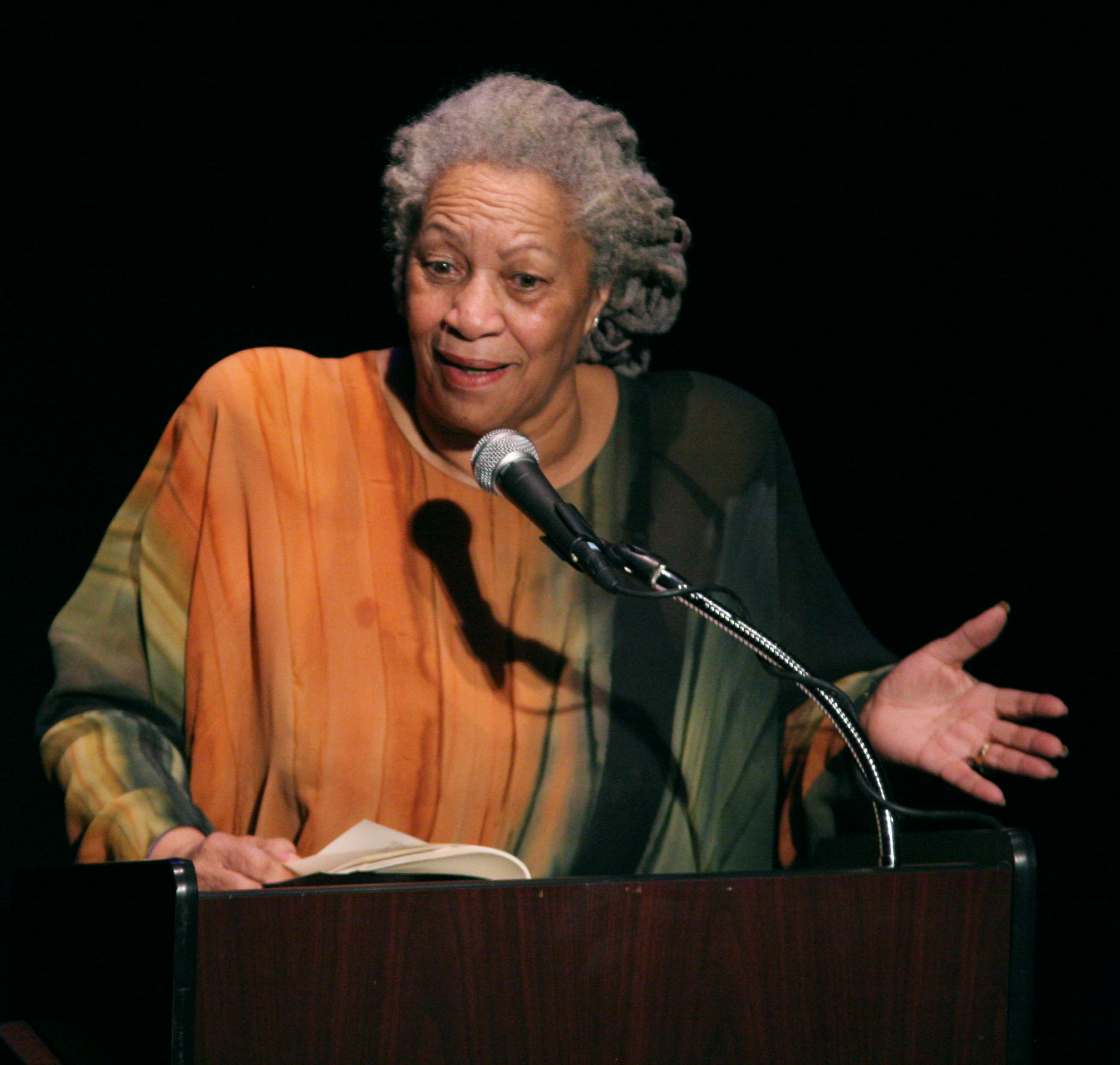

Beloved By Toni Morrison

My book club chose Beloved by Toni Morrison for our last meeting, so I was reading it along with the cases I’ve been discussing in this series. It’s a marvelous book, beautifully writtent. One piece of that craftsmanship is that although the events are not in chronological order we don’t have a problem following along because she gives a a few key words that place things in time.

This book can take different shapes for different people. I read it as stories about the people who endured the physical and psychological horrors of enslavement.

Kermit Roosevelt and Eric Foner describe the efforts of Black people to end slavery, by participating in abolition movements, by writing for themselves and for White people, and by the dangerous work of helping escapees. Some of these people appear in Beloved: John and Ella, for example, and Stamp Paid. The entire community helps newly freed people come to grips with their new status.

We know something about the cruelty of slavers from oral histories compiled by writers during the Depression and other sources. We have some first person accounts of slavery and escape. There’s some of that in the book. But for me, the power of Beloved lies in Morrison’s imagining of the reaction of newly freed people to freedom, and her instantiation of the psychic injuries inflicted by the slavers on her characters.

None of the psychological damage was discussed at the time as far as I know. And it’s certain that the voices of former slaves, their children, and their communities were never heard by the Supreme Court, which couldn’t even be bothered discussing the Colfax Massacre in US v. Cruikshank. I’ll discuss just two aspects of this powerful work.

1. Baby Suggs and Sethe react to being freed.

Baby Suggs was purchased by Mr. Garner from a slaver in North Carolina and taken with her children to Garner’s farm in Kentucky, Sweet Home. He was a decent slaver, who didn’t beat or mistreat his property. Years later he allowed Halle, Baby Suggs’ son, to buy her freedom. Garner takes her to Cincinnati. Morrison writes:

Of the two hard things—standing on her feet till she dropped or leaving her last and probably only living child—she chose the hard thing that made him happy, and never put to him the question she put to herself: What for? What does a sixty-odd-year-old slavewoman who walks like a three-legged dog need freedom for? And when she stepped foot on free ground she could not believe that Halle knew what she didn’t; that Halle, who had never drawn one free breath, knew that there was nothing like it in this world. It scared her.

Something’s the matter. What’s the matter? What’s the matter? she asked herself. She didn’t know what she looked like and was not curious. But suddenly she saw her hands and thought with a clarity as simple as it was dazzling, “These hands belong to me. These my hands.” Next she felt a knocking in her chest and discovered something else new: her own heartbeat. Had it been there all along? This pounding thing? She felt like a fool and began to laugh out loud. P. 166.

Sethe is Halle’s wife. A few years after Baby Suggs is freed, Sweet Home has been taken over by a vicious overseer, Schoolteacher. Sethe is pregnant, and is sexually assaulted and whipped senseless by Schoolteacher’s nephews. Sethe escapes. Just before crossing the river into Ohio, she gives birth to a daughter, Denver, and the last part of the trip is terrible. Then she reaches the safety of the home of Baby Suggs.

Sethe had had twenty-eight days—the travel of one whole moon—of unslaved life. … Days of healing, ease and real-talk. Days of company: knowing the names of forty, fifty other Negroes, their views, habits; where they had been and what done; of feeling their fun and sorrow along with her own, which made it better. One taught her the alphabet; another a stitch. All taught her how it felt to wake up at dawn and decide what to do with the day. … Bit by bit … she had claimed herself. Freeing yourself was one thing; claiming ownership of that freed self was another. P. 111-2.

The freedom Baby Suggs and Sethe share is touching in its smallness and fragility. I write about the abstract idea of freedom, as here, but this is so much more meaningful. In the long run, it’s not enough, but for these people in these moments it’s everything they can imagine.

2. Beloved.

Sethe’s 28 days of freedom end when Schoolteacher and other slavecatchers and the local sheriff find her. Sethe kills her two-year old daughter and tries to kill her two boys rather than let them suffer under slavery. Schoolteacher realizes she’s of no use as a slave, and leaves her in the hands of the sheriff. It’s unclear why, perhaps because of the intervention of anti-slavery advocates, but she only serves three months in jail and then is freed. This aspect of the story is loosely based on the life of Margaret Garner.

Sethe’s house is haunted. Everybody thinks it’s the murdered child. The community thinks it’s frightening, and cuts off Baby Suggs, Sethe, the two boys and Denver. Years later a strange woman appears, calling herself Beloved, the name engraved on the headstone Sethe purhased for her dead child. Beloved seems to exist as a separate, physical entity, but she has no history. The introduction of this character suggests she’s come back from the dead.

This is from the Wikipedia discussion of this part of the book:

Because of the suffering under slavery, most people who had been enslaved tried to repress these memories in an attempt to forget the past. This repression and dissociation from the past causes a fragmentation of the self and a loss of true identity. Sethe, Paul D., and Denver all suffered a loss of self, which could only be remedied when they were able to reconcile their pasts and memories of earlier identities. Beloved serves to remind these characters of their repressed memories, eventually leading to the reintegration of their selves. Fn. omitted.

I wonder about that first sentence. Morrison seems to confirm this reading in the forward to the Kindle edition.

In trying to make the slave experience intimate, I hoped the sense of things being both under control and out of control would be persuasive throughout; that the order and quietude of everyday life would be violently disrupted by the chaos of the needy dead; that the herculean effort to forget would be threatened by memory desperate to stay alive. To render enslavement as a personal experience, language must get out of the way. P. xvii.

The community of free Black people share the experience of haunting and sense the danger around Beloved. I assume they share some of the same psychic fragmentation. The community is there for the denoument, when the fragmentation seems to heal for all of them.

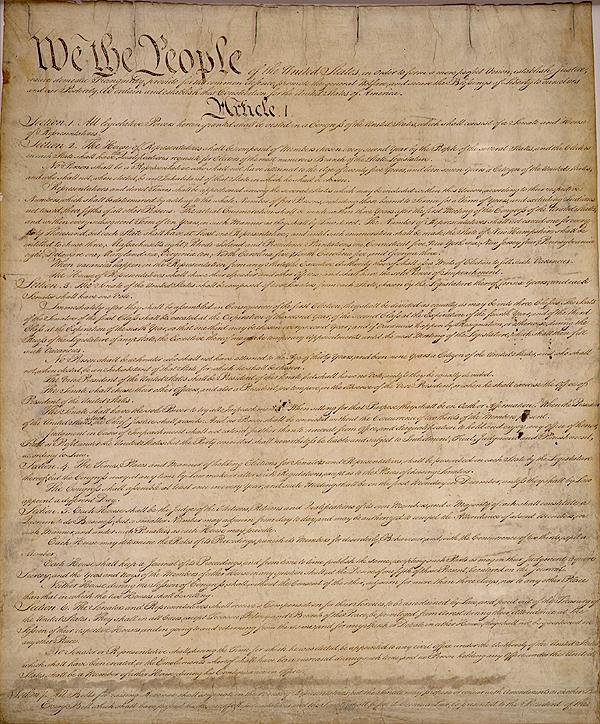

Now recall the offhand comment of Joseph Bradley in The Civil Rights Cases:

When a man has emerged from slavery, and, by the aid of beneficent legislation, has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state, there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws, and when his rights as a citizen or a man are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.

Just shake it off, like a hard hit in a soccer match. And Black people are expected to call Bradley “Mr. Justice”.

=====

Featured image credit.