The Injustice Of Our Rights Regime

We’ve seen the rise of the Holmes/Frankfurter theory that the Constitution protects few rights but protects them strongly. In practice that means that if a law infringes a constitutionally protected right, there is a heavy burden on the government to justify it, called strict scrutiny, but if there is no right, the law stands unless there is no rational basis for it.

Chapter 4 of Jamal Greene’s How Rights Went Wrong is titled Too Much Justice. The phrase comes from a dissent by William O. Brennan in a death penalty case, McClesky v. Kemp. McClesky showed that in Georgia, Black people convicted of killing white people were disproportionately sentenced to execution. Lewis Powell constructed a slippery slope argument to the effect that any kind of defendant might show such disproportion and then what? Brennan wrote that McClesky would die because Powell was afraid of too much justice.

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, (1973) is similar. The plaintiffs were the families of kids in the Edgewood district of the Defendant San Antonio Independent School District (SAISD). They claimed that the funding system for Texas school districts was unconstitutional because it effectively deprived their kids of a decent education.

Greene begins his discussion with a description of the school that the Rodriguez kids attended:

The school building was falling apart. Many of the windows were broken. Many of the teachers were uncertified and underpaid; a third of them had to be replaced every year. Temperatures in San Antonio reached the mid-80s that day, but the school had no air-conditioning. There was no toilet paper in the restrooms. A bat colony had nested on at least one floor of the school. P. 94.

Powell wrote the 5-4 majority opinion. He starts with a detailed history and description of the funding system which is based on property taxes in each district. Edgewood had the lowest property value in the SAISD. Texas capped property tax rates. Even though Edgewood had a higher property tax rate, it raised substantially less than other school districts in the SAISD. Edgewood had $356 per student compared with $596 in Alamo Heights, which had the highest property tax valuation.

Powell’s discussion of applicable law starts with a discussion of the decision below. A three-judge panel of the District Court found that the Texas funding system discriminated on the basis of wealth, that wealth was a suspect category, that education was a fundamental right, and therefore the State was required to carry a heavy burden of proof justifying this system. Of course Texas could not show a compelling reason for the funding system.

Powell rejects that analysis. He doesn’t bother with the actual facts of the case as they affect the plaintiff. His only interest is the nature of the legal rights asserted by the plaintiff.

We must decide, first, whether the Texas system of financing public education operates to the disadvantage of some suspect class or impinges upon a fundamental right explicitly or implicitly protected by the Constitution, thereby requiring strict judicial scrutiny.

Powell says the wealth discrimination shown here is unlike any other kind of wealth discrimination accepted by SCOTUS to date. Later he says the same about education as a fundamental right.

Wealth Discrimination

The lower court found that poorer people in San Antonio received “less expensive” educations that those in weather districts. It held that that was enough to find wealth discrimination. Powell says that’s simplistic. Powell says he has to find a class of disadvantaged poor people that can be defined in the customary language of equal protection cases; and then evaluate the relative — rather than absolute — nature of the asserted deprivation is of significant consequence.”

He says there are three possible ways to show discrimination.

1. People with incomes below an identifiable and relevant level, which he calls “functionally indigent” (my quotes).

2. People relatively poorer than others

3. People who live in poor districts regardlesss of their incomes.

He says he will stick to SCOTUS precedents. He offers two groups where wealth discrimination has been found. He says that in those cases, the group discriminated against was so poor they could not pay, and thus were denied a benefit available to wealthier people. We are treated to several pages of cases, an expanded form of what lawyers call string-citing. Based on this analysis, the Texas plaintiffs must be relying on Powell’s first definition of a class of poor people.

But that is no good. There are equally poor people in wealthier districts. There’s a study saying that poor people tend to live in districts with a high concentration of warehouses and industry, which would support a higher property tax rate. That’s tnot the case here.

Anyway, SCOTUS precedents require that the class be denied the benefit. Here the kids are getting an education, and some money, and that’s good enough under the Equal Protection Clause.

… [I]n view of the infinite variables affecting the educational process, can any system assure equal quality of education except in the most relative sense. Texas asserts that the Minimum Foundation Program provides an “adequate” education for all children in the State.

Who can tell? It’s all so complicated.

The right to education

Powell says SCOTUS is committed to education as an important right. Then he says that education is just another service offered by the state. The Equal Protection Clause doesn’t require equality in that service. Powell says education isn’t a fundamental right set out in our Constitution.

It is not the province of this Court to create substantive constitutional rights in the name of guaranteeing equal protection of the laws.

Discussion

1. There’s more. Lots more. And that’s not counting the 114 footnotes. But I doubt many EW readers got far into the discussion before saying to themselves, But what about the kids going to school with BATS? The bat colony isn’t mentioned in either the SCOTUS decision or that of the lower court. The lawyers are so wound up about the funding mechanism and court-created rules about classification that they ignored the actual outcome: kids are going to school with bats!

2. Powell gives us a slippery slope argument: if we say kids shouldn’t have to go to school with bats, we might have to say they have to be fed a nutritious meal at school.

3. Greene describes Powell’s background in some detail. Reading between the Ines, Powell seems like one of those genteel Southern Politicians, the ones who would never use the N-word in public, but can’t quite pronounce Negro, especially at the country club.

4, The 14th Amendment says in part that no state is permitted to “… deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” How hard is it to apply that rule to kids going to school with bats?

5. This case and hundreds of others are the direct result of the refusal of SCOTUS to enforce the 14th Amendment. Instead, we get blindingly stupid holdings based on what John Roberts called the dignity of the state. A state that makes kids go to school with bats and calls that an “adequate” education has no claim to dignity.

,

,

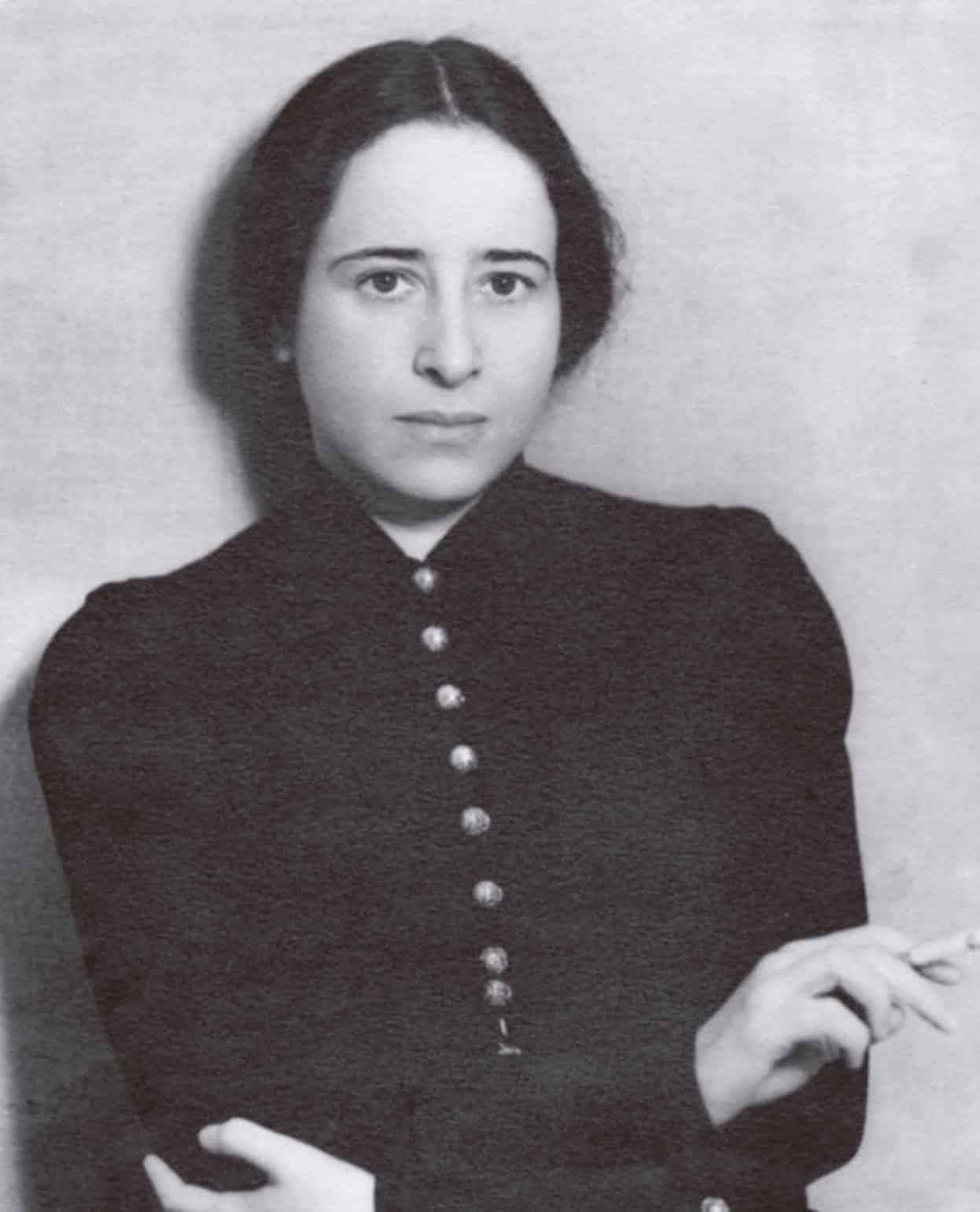

Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Arendt#/media/File:Hannah_Arendt_1933.jpg

Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Arendt#/media/File:Hannah_Arendt_1933.jpg