Evolution And Individuals

Posts in this series

The Individual In Contemporary Society

Evolution And Individuals

Maturing In US Society

Human Individuality

Expressions Of Individuality In Democracy

Neoliberal Individuals

The first post in this series took up the question of the nature of the individual in contemporary US society. I think answering this question is necessary if we are to create a theory of government for our time.

An evolutionary tale

Let’s start with a story. I can’t remember where I found the story I’m about to tell. Maybe it was The Evolution of Agency by Michael Tomasello, or The Dawn Of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow, or maybe Eve by Cat Bohannon, or maybe something I ran across while writing about those books, or a combination of these.

Of course we will never know the “truth” about evolution, and there’s always a danger of falling for just-so stories. But this tale seems plausible and I’ll point out some circumstantial evidence.

As our ancestors evolved, they moved around in loose groups. The change began about 6 million years ago. Perhaps a group of primates got cut off from the rest by a rising river or an earthquake, or maybe they just wandered too far to be reunited. Conditions changed in the new area, resulting in less food. This led to smaller and weaker creatures. They were easy prey for other larger, stronger creatures with sharper ears, eyes and noses.

Their survival came to depend on their ability to cooperate. One form of cooperation might have been scavenging. After one of the big predators made a kill and gorged, the scavengers appear: jackals, hyenas, vultures. Our ancestors may have worked together. One or more scare off the other scavengers while others rip at the carcass. They run away and share the prize. Or it might have been cooperative hunting, where the victory is, again, shared.

Chimpanzees and other primates in and near our line of evolution do not cooperate in hunting. They may work side by side, but if they succeed, there is no sharing. Every chimp grabs what it can, whether or not it participated in the hunt.

In either case, or otherwise, about two million years ago, they began to use tools. Maybe they started with sticks and rocks. Eventually they learned how shape tools. This is a learned and teachable behavior.

Social cooperation requires the ability to recognize the existence of others as similar to oneself. When I feel a certain way, my body does X. If I see a creature doing X, I assume they feel like I would if I exhibited that behavior. From there, more and more complex social interactions can develop. Hunting can proceed by explicit agreement. Simple hand signals and noises can be used to indicate planning and the means of cooperation.

Over the next 1.6 million years, brains gradually grow larger. From the shape of fossil skulls we can guess that the parts of the head that grew are those necessary to accommodate the parts of the brain used in social interactions. The larger heads change the way the female body was shaped and the way they gave birth. The difficulty of birth required increased social cooperation, probably centered on the females.

The infants were dependent far longer than their primate ancestors. This was another force leading to increased social cooperation. Bohannon speculates that the primary source of language was the interaction of mother and infant, because they spent so much time together. Eventually we became Human, and as Graeber and Wengrow put it: we began doing human things.

Some evidence

There are a number o papers showing that there are regions in primate brains that are specific to facial recognition. There other papers showing that primates make and recognize some facial expressions. Another group says that the parts of the brain responsible for speech are separate from the parts that perform thinking operations.

1. Facial-recognition regions. In this article from Scientific American, Doris Y. Tsao, a professor at Berkeley, explains how she and her colleagues discovered specific regions in the brain whose function is to recognize faces. She performed fMRI studies on monkeys, creatures with whom we share a common ancestor. When fellow scientists objected that fMRI is inconclusive, she and her colleagues tested individual neurons in the patches, and found that all but a tiny number of cells in those patches responded solely to faces.

2. Primates recognize individual faces of conspecifics (members of their species) and some recpgmize human faces. They also read at least a few emotions from the facial expressions of conspecifics. A example is the teeth-bared grimace, which has different meanings in different species. It is common among chimpanzees, monkeys of many species, and in some canids. The teeth-bared grimace can look somewhat like the human smile. It is used in several papers I read as an example of the evolutionary roots of human facial expressions. Here’s one example from 2001. From the introduction:

One of the central questions in human evolution is the origin of human sociality and ultimately, human culture. In the search for the origin of social intelligence in humans, much attention is focused on the evolution of the brain and consciousness. Many aspects of human cognition and behavior are best explained with reference to millions of years of evolution in a social context Human brainpower can thus be explained, in part, by increasing social demands over the course of human prehistory. Cites omitted.

3. We do not need words to think. This was news to me, because I have a bare acquaintance with the fundamental ideas of Noam Chomsky. But this article in Scientific American asserts that the regions of the brain used in problem-solving are separate from the centers used in language. The paper surveys dozens of studies. It finds several kinds of evidence.

First, there are studies of thinking in aphasic people. These are people who cannot use language, but nevertheless are able to solve problems, make plans, read faces and perform other tasks requiring mental processing.

Second, there are many fMRI studies showing that when people are solving problems, like doing Sudoku, the speech centers are not active.

Third, language is optimized for communication, not for thinking. There are ambiguities in words and sentence structures that would make problems solving fuzzy.

The areas of the brain that do language are late developments. We didn’t need complex language to survive. We could learn the techniques for knapping rocks into tools by watching and practicing. But the more we learn, the more we need language to share knowledge. If we think of knowledge as an internal state of mind, we can see language as a way to communicate that knowledge, that internal state, to others.

It seems me that each of these supports the idea that human evolution is oriented towards social cooperation. Our survival as a species has been built around our ability to work together to survive together. For us, evolution isn’t driven by the survival of an individual, but by the survival of our group. Our genes aren’t just ours, we share many of them with others in our kinship group. For most of our evolutionary history, kinship was at the root of our social groups. At least I think that’s probably so. Thus, if our cousins survive, many of our genes go with them.

But cooperation isn’t the only mode of interaction. All of our abilities can be used for more than one purpose. For example, our social skills can be used to deceive others. That’s always been true, and some of our primate relatives can do it too. We should assume that our earliest ancestors could and did take advantage of those skills and use them for individual gain. And we should assume that societies develop systems for coping with those non-cooperative behaviors. I think deception developed side by side with our social skills, and may have driven our social evolution to some extent.

But I think that at bottom, cooperation is a fundamental aspect of our selves, and that the capacity to deceive is a variant of cooperation skills. I think our first social control systems developed out of cooperation in reaction to those who refused to cooperate. Is that too optimistic?

Implications

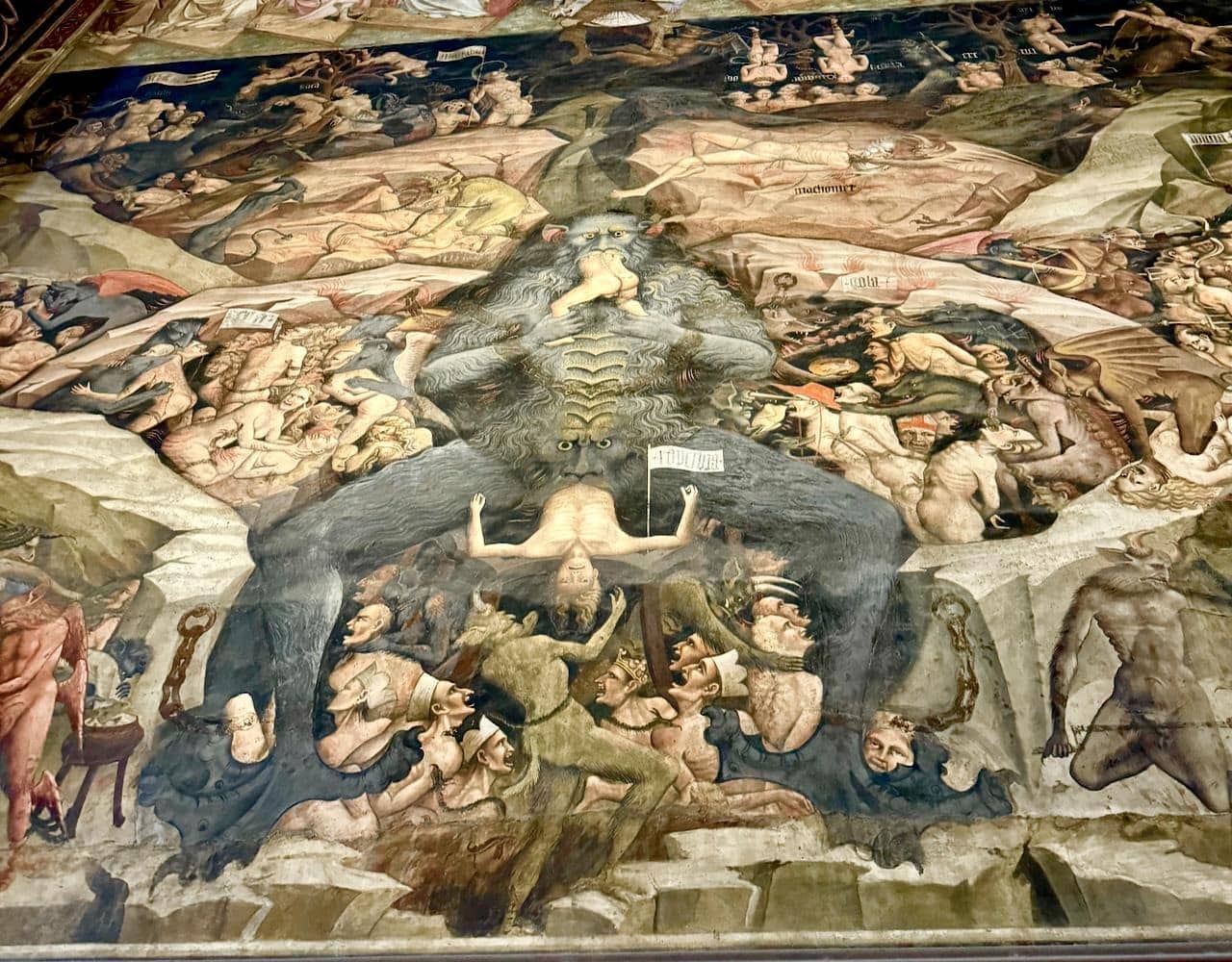

This story is the opposite of the dominant theory of our times, neoliberalism. Our society tells us that we are nothing more than isolated individuals competing in a fiercely competitive arena for the resources we need to survive. Neoliberalism is at the heart of US capitalism, the economic system established by the rich and powerful. Many of our own ancestors fought back against aggressive capitalists, but were crushed again and again by a combination of state and federal armed forces, and private armies.

Of course, we don’t teach that history any more, but you can get a start reading A People’s History Of The United States by Howard Zinn. We occasionally remember that Black people resisted, sometimes violently, but we never talk about the coal miners, the factory workers, and small farmers resisting the grotesque demands of the filthy rich. These men and women fought together. I mean literal fighting, with guns and pitchforks. Eventually they won minimal legal protection.

Then their children threw it away. They bought into a story about Lone Rangers and Honest Sheriffs and Invisible Hands.

These are people who don’t know their own history. Maybe we need to teach them their about their ancestors. All of their ancestors.

none

none

,

,