Democracy Against Capitalism: Markets

While the development of capitalism certainly presupposes the existence of markets and trade, there is no warrant for assuming that markets and trade, which have existed throughout recorded history, are inherently, or even tendentially, capitalist. Democracy Against Capitalism, Kindle Loc. 2355

Human beings have always enjoyed markets and trade. In The Histories by Herodotus, written in the Fifth Century BCE, there are many mentions of markets and trade. In this excerpt, he describes a huge excavation project, and adds this:

Now there is a meadow there, in which there was made for them a market and a place for buying and selling; and great quantities of corn came for them regularly from Asia, ready ground. Book VII § 23.

There certainly wasn’t any such thing as capitalism 2500 years ago, but people still bought and sold in markets and carried goods to markets over remarkable distances. Markets and trade are found in all societies as far back as we can see. In a society with complex division of labor, they seem essential as a mechanism for distribution of production. Wood takes up the question of the role of markets in capitalist societies in several places. For example:

It is not capitalism or the market as an ‘option’ or opportunity that needs to be explained, but the emergence of capitalism and the capitalist market as an imperative. Kindle Loc. 2360

One important aspects of the transformation of feudalism into capitalism in England was the enclosure of lands. That concentrated land ownership in the hands of the aristocrats and landed gentry, a very small group. Some small farmers were able to participate in the market for land leases, giving them access to the means of production and maintaining and reproducing themselves. But the only way for them to raise cash to pay their rient was to sell their produce in the market. The small group that controlled most of the land used markets to get cash as well, having no need for all they produced and desiring cash returns. Instead of market as optional means of distribution, markets became imperative.

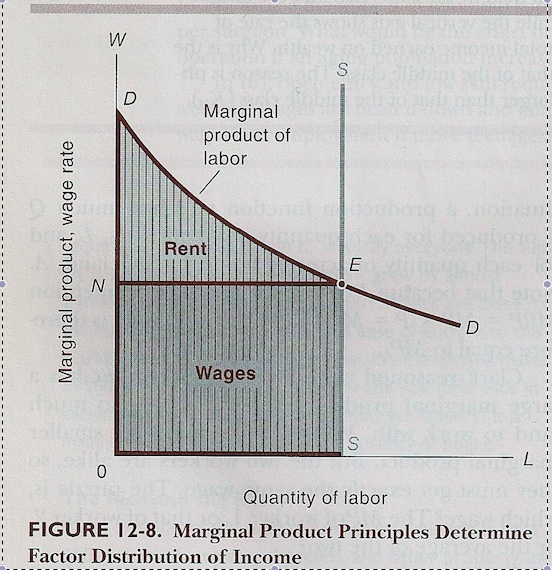

Agricultural workers with no access to the market for leases were forced to sell their labor to those with access, thus becoming participants in a labor market, and to use their wages to buy the food and other goods they produced. This is the early stage of capitalism, when its drives become clearer and more demanding. Small leaseholders can only raise the cash they need to pay rent by selling their produce. Their profits increase if they can extract more labor from the workers or pay them less. They are competing with other small leaseholders, so they benefit by crushing their competition or by crushing their workers. These are the seeds of the transformation identified by Wood.

Wood is clear that there is nothing inherently problematic with markets as means of distribution. The problem is the ideology and use of markets in capitalist systems, which Wood despises. First, she rejects the theory that markets are self-regulating,

… the guarantor of a ‘rational’ economy. I shall not explicate that distinction here, except to say that the ‘rational’ economy guaranteed by market disciplines, together with the price mechanism on which they depend, is based on one irreducible requirement, the commodification of labour power and its subjection to the same imperatives of competition that determine the movements of other economic ‘factors’. Kindle Loc. 5679,

This is the same idea we see in Polanyi’s The Great Transformation. He describes labor as a fictitious commodity, as I discuss here. Like most European intellectuals, Polanyi was well-versed in Marxist thought, but there is little direct evidence of that in his book, a point Wood makes. Kindle Loc. 3074. It’s another illustration of the way Marx’ historical materialism has influenced intellectuals. It’s the method that’s important, but Marx’ conclusions and even his history and sociology are open to argument and correction. I do think Wood herself is less open to questioning and correcting what she finds in the Marx canon; I can’t find much where she engages with her contemporaries outside her fellow Marxists. I’d welcome a correction on this.

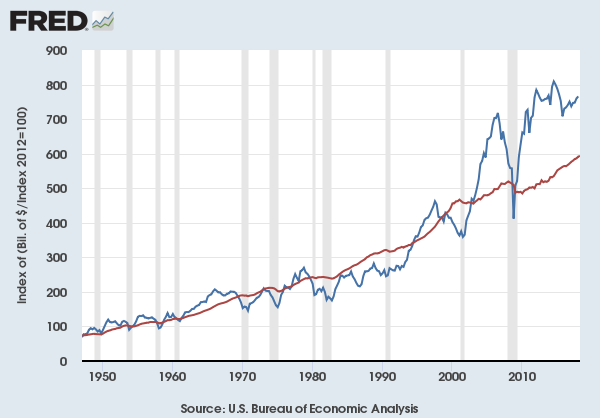

Criticism of the notion of a self-regulating market has recently risen to a level that makes it almost impossible to take it seriously. After the steady string of economic crashes brought on by deregulation, only the most rigid among us cling to that idea. But it’s useful to remember that Wood wrote this in the early 1990s.

Second, Wood says that capitalists use markets to further the ends of capitalism instead of to meet the needs of human beings. The market is a tool to establish dominance and control over producers. Wood puts it this way:

I have suggested throughout this book that the capitalist market is a political as well as an economic space, a terrain not simply of freedom and choice but of domination and coercion. Kindle Loc. 5997.

Indeed, throughout the book Wood argues that the market is an imperative, not a choice in a capitalist society. Few of us have the ability to produce to meet our needs. If we want to eat, we are forced to sell our labor. Even those who can produce goods and services must, as the tenant farmers Wood describes, sell their goods and services to get cash for other needs. Capitalists produce those things they think they can sell without little regard to the long-term consequences, and without any input from interests affected by such production. Wood quotes Marx from Das Kapital:

The real barrier of capitalist production is capital itself. It is that capital and its self-expansion appear as the starting and the closing point, the motive and the purpose of production; that production is only production for capital and not vice versa, the means of production are not mere means for a constant expansion of the living process of the society of producers. Kindle Loc. 2647

In other words, the point of capitalism is to provide returns to capital. The point isn’t to make life easier or better for the vast majority of workers and citizens. In the exact same way, the point of markets is to provide a return to capital, not to provide the best allocation of resources or to provide the lowest price for goods and services. We see this more clearly as neoliberalism tightens its grip on the economy. Big Pharma is a good example.

These two criticisms are closely connected to the division of the political sphere from the economic sphere. We can think of the “market” as a proxy for the economic sphere, which in capitalist systems is separated from the political sphere. Wood puts it this way:

… the so-called economy has acquired a life of its own, completely outside the ambit of citizenship, political freedom, or democratic accountability. Kindle Loc. 4579.

The separation of the political and economic spheres has given private interests the dominant position in the lives of workers. They control the hours worked, the nature of the work, the kinds of things that are produced. This control arises through the property relations established and enforced by the state. With the sanction of the state, these private interests have the power to decide people’s income and whether they are allowed to earn an income at all. We even see private interests setting limits on the speech and assembly rights of individuals. Private interests have the power to limit health care benefits, vacations, and childbirth leave, just to name a few. Legislation to assert the interests of workers is routinely defeated, and when not defeated, is always watered down, in the name of efficiency, or of profit, or of the absolute rights of people/corporate entities to the property they control.

I don’t see any argument here that could not be made by a neutral observer of modern neoliberal capitalism.