Quasi-Objects for Moderns and Premoderns

Posts in this series. In the first post I give some background on We Have Never Been Modern by Bruno Latour. The second post describes quasi-objects. In this post I try to explain why Latour thinks this is an important distinction.

The Moderns

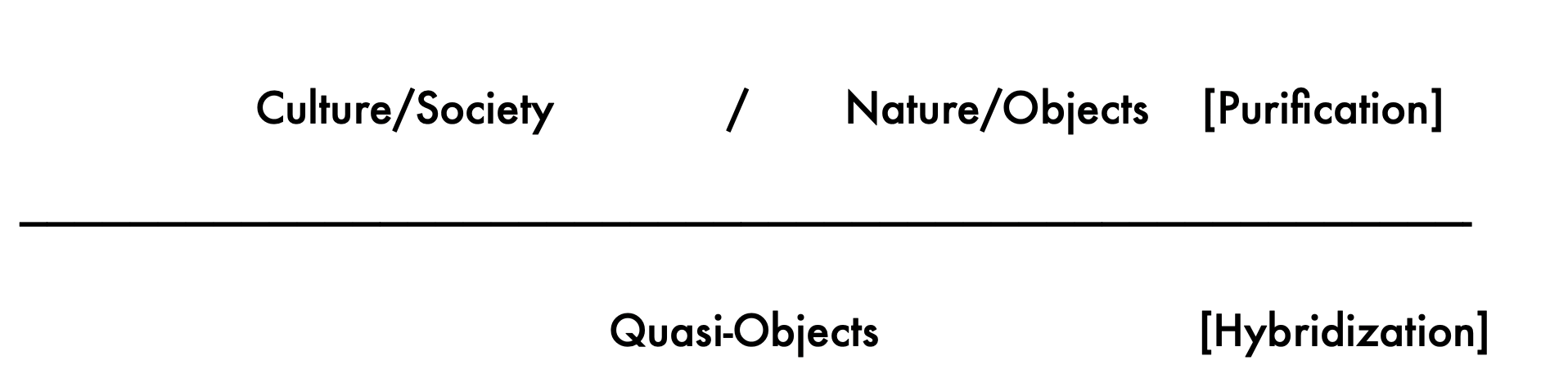

Quasi-objects play a central role in Latour’s thinking. He uses a diagram similar to this

Above the line we see the separation of culture and nature, driven by the work of purification. Below the line we have quasi-objects, created by the work of hybridization. The work of purification is acknowledged to be a central part of our self-understanding. As a society we are conscious of this work, and we think it is important. Below the line is the vast bulk of the work we do in contemporary society, and have done for some decades. Our productive lives consist in the creation of quasi-objects, and our social structures revolve around these new creations.

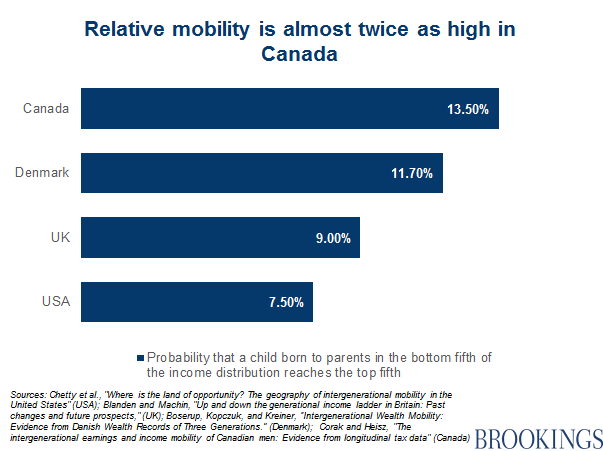

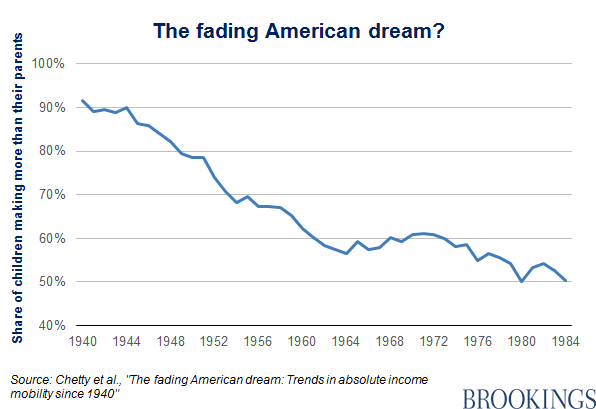

But we do not subject quasi-objects to study, we do not pay serious attention to them, or demand accountability for their consequences. They are, for the most part, invisible to our understanding of our society. At most, we notice them when their consequences cannot be ignored even by the most committed moderns. Here’s a horrifying example.

The Premoderns

Latour contrasts this description of the condition of modernity with his discussion of pre-moderns:

So are the moderns aware of what they are doing [in the act of hybridization] or not? The solution to the paradox may not be too hard to find if we look at what anthropologists tell us of the premoderns. To undertake hybridization, it is always necessary to believe that it has no serious consequences for the constitutional order. There are two ways of taking this precaution. The first consists in thoroughly thinking through the close connections between the social and the natural order so that no dangerous hybrid will be introduced carelessly.

The second one consists in bracketing off entirely the work of hybridization on the one hand and the dual social and natural order on the other. While the moderns insure themselves by not thinking at all about the consequences of their innovations for the social order, the premoderns – if we are to believe the anthropologists – dwell endlessly and obsessively on those connections between nature and culture. To put it crudely: those who think the most about [quasi-objects] circumscribe them as much as possible, whereas those who choose to ignore them by insulating them from any dangerous consequences develop them to the utmost.

The premoderns are all monists in the constitution of their nature-cultures. ‘The native is a logical hoarder’, writes Claude Lévi-Strauss; ‘he is forever tying the threads, unceasingly turning over all the aspects of reality, whether physical, social or mental’. By saturating the mixes of divine, human and natural elements with concepts, the premoderns limit the practical expansion of these mixes. It is the impossibility of changing the social order without modifying the natural order – and vice versa – that has obliged the premoderns to exercise the greatest prudence. Every monster becomes visible and thinkable and explicitly poses serious problems for the social order, the cosmos, or divine laws. Kindle loc. 686, cites omitted; paragraphing and emphasis mine.

The moderns feel free to ignore all the restrictions the premoderns imposed on creation of quasi-objects. They cannot see themselves as a continuation of the premoderns but insist that they are completely new and different.

The Divine

As the foregoing quote shows, the premoderns included the Divine in their conception of the world. Both Hobbes and Boyle discuss the Almighty in their treatises, but they call on a distant God, one not involved in the discovery of natural law or the laws of society. Their God created the world and the natural laws that operate in it, and then left the construction of society and the discovery of the laws of nature to human beings. Latour refers to this vision of the Almighty as the Crossed-Out God. This Crossed-Out God lives in our hearts, but only in our hearts. Today we would call this Deism; remember that many of the Founding Fathers were Deists.

Discussion

The history of Galileo and the Copernican Theory gives us a nice example. By Latour’s definition, Galileo lived at the end of the premodern era (1564-1642). Like Boyle, he applied some of the tenets of the scientific method. The details are laid out in Wikipedia. Galileo adopted the Copernican theory in the early 1600s based on his own published observations. There were two kinds of objections to heliocentrism. One was scientific, largely the work of Tycho Brahe using Galileo’s own methods.

The other was religious, based on several passages of the Bible. Perhaps the most obvious of these is Ecclesiastes 1:5; here’s the King James translation:

The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose.

That clearly conflicts with Galileo’s findings and the Copernican theory. Galileo took up the challenge directly, arguing in an unpublished but widely read letter that he was right, and that the Bible should be read as the authority on matters of faith and morals, but not on nature. The Catholic Church claimed that Galileo was interpreting the Bible, which under Church doctrine was solely the province of the Church, and looked dangerously like Protestantism. Galileo’s views were declared heretical, his books and others on the Copernican theory were banned in 1616 and he was ordered not to defend his opinion about the motion of the earth.

Let’s examine this conflict in Latour’s terms. The premodern Catholic Hierarchy saw that this new idea about nature would have a big impact on the social structure. The Church read the Bible as an authority on all that it contained, as the inspired work of the Deity. Galileo’s data calls into question the authority of the Bible. If the Bible gets nature wrong, what else does it get wrong? How can the Deity be wrong? Was God intentionally misleading his creatures? In his reply, Galileo indeed questions the Church as the ultimate interpreter of the Bible, asserting that his way of understanding the Bible is better than that of the Pope.

Ideas like these could disrupt everyone’s life, destroying their faith, destroying their trust in the dominant class and the social structure it led, and leading in uncontrollable directions. With the incredible violence that followed the Reformation, these are reasonable concerns. [1]

We moderns just dismiss these worries. We think the Church acted like barbarians. We argue that the Church was simply trying to protect its privileged position, and the privileges of the hierarchy and of monarchs ruling by divine right. We say they denied facts in front of them and and used their power wrongfully. There is an element of cynicism in our dismissal, a denial of actual concerns that the Church might have had for its flock, a denial of the deep religiosity that stirred many clerics and the laity. Maybe there’s also a touch of arrogance, a belief that all scientific understanding and progress is automatically good.

I probably would have agreed before I read Latour. But look at precisely what the Church ordered: Galileo was free to follow his ideas as theories. He was merely ordered not to teach that his theories were physically true. That’s pretty much how we moderns think of his theory. We know it’s physically true, but we talk about sunrise and sunset. I don’t get up from my desk after an hour of reading and say to myself oh look, the earth has spun 15 degrees on its axis. For all the good it does in the world of theory and calculation, it still contradicts what we and our ancestors for millennia see with our own eyes.

Maybe we aren’t so modern after all.

=========

[1] In exactly the same way, the Industrial Revolution, and the Darwinian revolution caused enormous social uproar and misery. This is a central point of Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation. I discuss the book in a series indexed here. I discuss Polanyi’s view of the social problems created by disruptive change in this post.

\

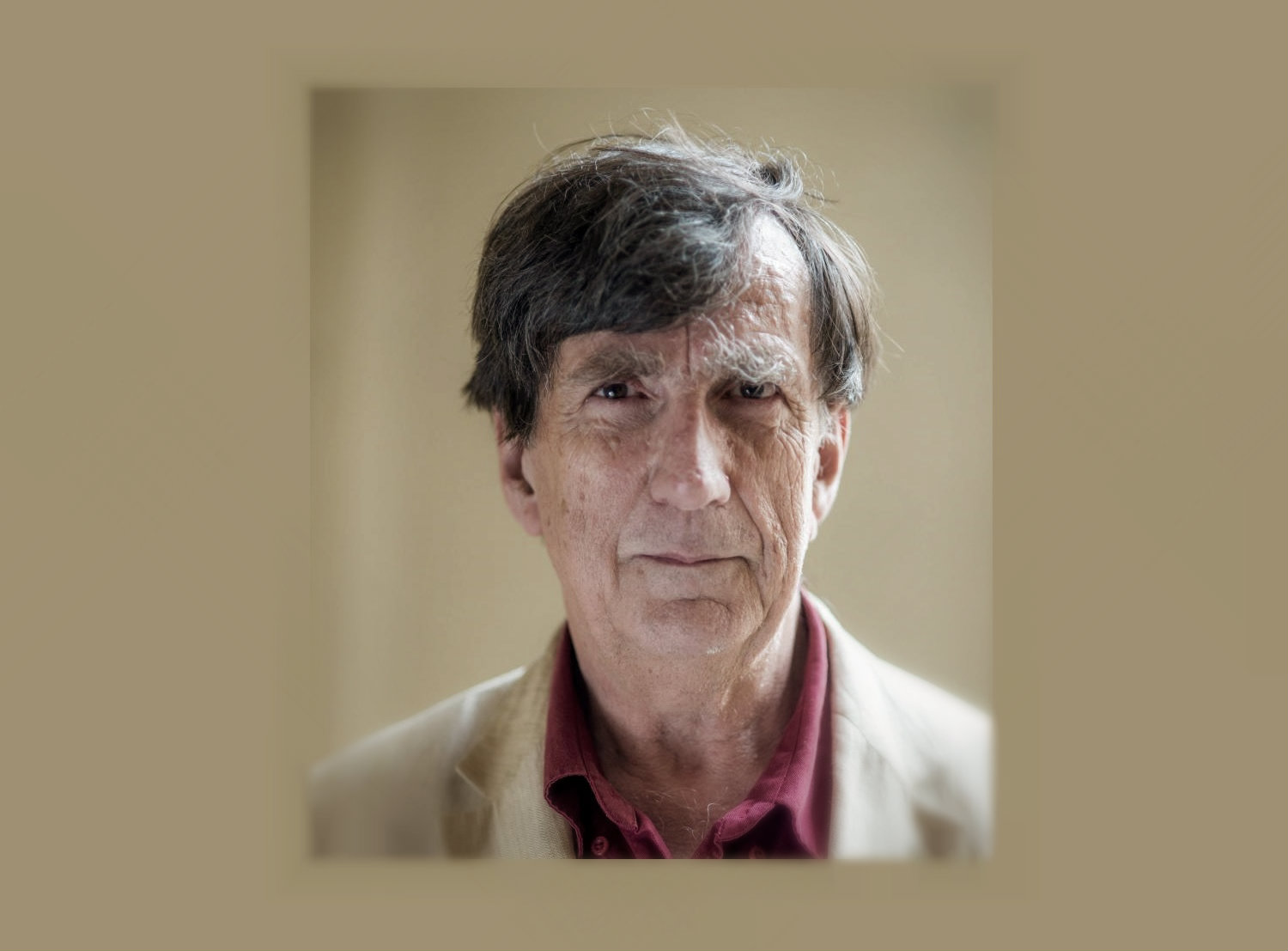

I’ve been reading We Have Never Been Modern, a 1991 book by the French thinker Bruno Latour, pictured above. It doesn’t lend itself to my usual treatment, reading and commenting on a chapter or two. Instead, I’m going to try to lay out some of the aspects that seem important enough to merit discussion.

I’ve been reading We Have Never Been Modern, a 1991 book by the French thinker Bruno Latour, pictured above. It doesn’t lend itself to my usual treatment, reading and commenting on a chapter or two. Instead, I’m going to try to lay out some of the aspects that seem important enough to merit discussion.