Social Security And Other Entitlements

Posts in this series

The Deficit Myth By Stephanie Kelton: Introduction And Index

Debunking The Deficit Myth

MMT On Inflation

Reflections On The Deficit Myth

The National Debt Is Soooooo Big

The Wonkish Myth Of Crowding Out

MMT On International Trade

Chapter 6 of Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth discusses the perennial conservative effort to cut entitlements. [1] Kelton defines entitlements as statutory determinations that people who meet certain criteria are entitled to certain defined payments. She discusses several of the most widely used entitlements, Social Security, Social Security Disability, Medicare, Medicaid, SNAP and welfare.

Kelton describes the history of these programs, beginning with Franklin Delano Roosevelt. FDR saw Social Security as the first step towards a comprehensive array of programs that would insure that the citizens would be truly free. He specifically chose to fund Social Security with a tax, so that people would feel ownership, making it harder for politicians to vote to take away those benefits. it worked. People are firmly attached to the program. The money is put into a “trust fund”, which holds it in the form of special non-negotiable US Treasury notes.

Politicians, goaded by their rich donors, try to weasel around this powerful attachment. They start with basic debt hysteria: the Trust Funds are Going Bust! [2] They base this on the reports of the Trustees of the trust funds, who are directed to estimate the date on which the Social Security Trust Fund will run out of money. If that happens. under current law, Social Security payments will be cut. They then claim that all they want to do is put Social Security on a firm financial footing. But they have to act now. Now! And somehow the only possible actions are benefit cuts and tax hikes for working people.

This worked the last time the deficit hawks of both parties tried it. Under Ronald Reagan both parties agreed to cut benefits, raise the retirement age, and increase FICA taxes. This increase in tax revenues was then used as cover for tax cuts for the filthy rich. The effort was led by Alan Greenspan, an Ayn Rand devotee, and no friend of working people.

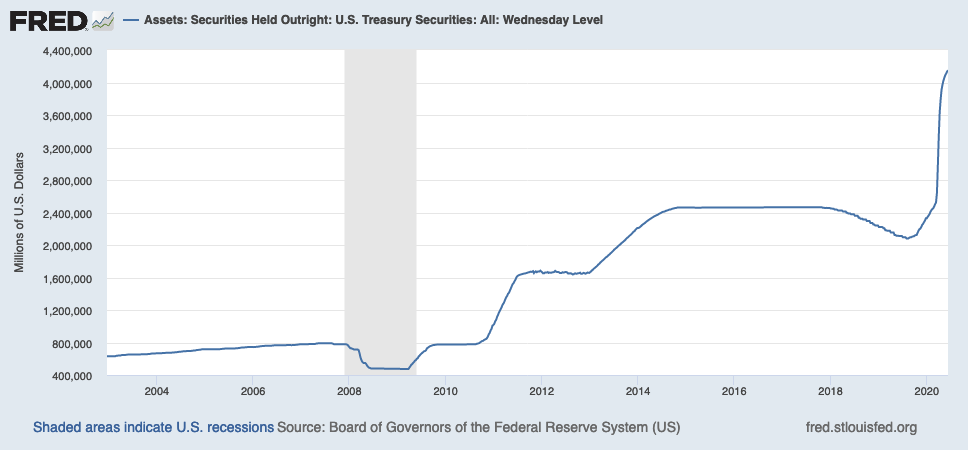

Medicare is also funded with specific taxes which are put into a special Treasury account, and has a board of trustees. But there’s a big difference. Under Medicare statutes, the Treasury is directed to make all payments, regardless of the state of the trusts. So, every report of the Trustees says that Medicare is just fine. We could do the same for Social Security, and all other entitlements. That simple change would solve the problem. That’s what Kelton recommends, and it makes perfect sense under Modern Monetary Theory.

Liberals offer other solutions. We could raise the cap on the wages subject to FICA taxes. We could have a millionaires tax that would fund Social Security and other entitlements. We could impose a tiny tax on securities transactions and direct the funds to the various trust funds. I don’t think Kelton is opposed to funding social programs with dedicated taxes, and I don’t think she would object to any of these ideas or to the idea that paying dedicated taxes adds to a sense of ownership. The issue is that people think it must be this way. It doesn’t. MMT teaches us that we have the money to do what we want to do.

Taking the pressure off of funding sources does two things. It relieves the anxiety of the older people, the group Enzi is trying to frighten. But it also frees us to focus on the actual needs of the future and to plan for them. As people get older, their needs change. They need more medical care, more help at home, more and different kinds of medicine, different furniture, different living arrangements, and so on. Their desires change, too. They want to do more travel, to spend more time with their spread-out families, and to enjoy more varied kinds of entertainment, restaurants, and other kinds of get-togethers.

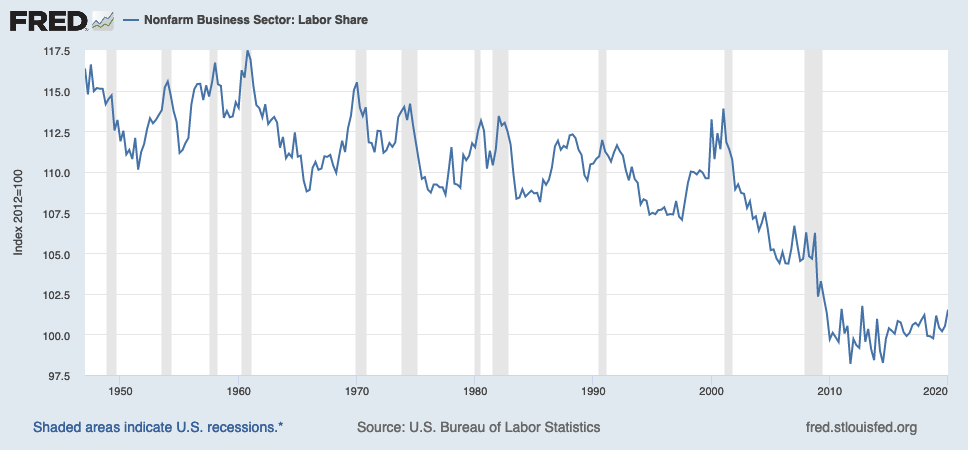

Kelton, writing before the pandemic hit, calls for the expansion of Social Security. She points out that it was originally intended as one leg of a “three-legged stool” of retirement planning. The other two were personal savings and pensions from employment. The latter two are disappearing.

Before the pandemic, 40% of us didn’t have savings of $400 for emergencies. Once upon a time, employers provided defined-benefit plans, which promised to pay retirees a specific amount based on pay and length of service. [3] Most of those plans are gone. Kelton cites a particularly ugly case where McDonnell-Douglas closed a plant in Tulsa and terminated a defined-benefit plan in part because so many workers were approaching retirement age when they could collect a full pension with terrible results for older workers. [4] Congress established the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation to cover a portion of the lost benefits when companies terminate plans. The benefits guaranteed are absurdly low.

Employers now establish defined-contribution plans like 401(k)s. The track record of these plans shows that they are an inadequate substitute for most people. They are expensive, as members pay administration costs as well as management fees to Wall Street. The national average all-in fee is 2.2%. The Center for American Progress estimates that “… the typical American worker who earns a median salary starting at age 25 will pay about $138,336 in 401(k) fees over their lifetime.” Median account sizes vary substantially by age. For those over 50, the median is around $66K. The average is much higher, around 200K, showing that these plans primarily benefit the wealthy.

Taken together, these facts show a critical need for a stronger Social Security system, not the cuts sought by conservatives.

Other entitlement programs are under attack from the deficit hawks. There are constant efforts to make it more difficult to enroll in Medicaid, like work requirements or co-pays. Fifteen states haven’t implemented Medicaid expansion as permitted by Obamacare; Missouri just added a constitutional amendment requiring implementation. SNAP benefits are under constant assault by Republicans in the name of frugality, as if these $68 billion in a 4$ trillion budget was meaningful compared to the needs of the population served.

Kelton’s point is that we have the money. We need the will to establish priorities that match our moral values, and a Congress that will legislate those priorities.

=====

[Graphic via Grand Rapids Community Media Center under Creative Commons license-Attribution, No Derivatives]

[1] It’s one of the more bizarre conservative demands. Social Security is a crucial element of the financial lives of a very large number of older Americans; approximately 40% of retirees would have incomes near or below the poverty line without it. That’s about 21 million voters who are more likely to vote for conservatives. To protect themselves from voter anger, conservatives explicitly call for the “I’ve got mine, screw you Jack” approach: their proposals always exempt today’s older crowd, as if the younger citizens won’t notice that their parents are safe but they aren’t and neither will their parents.

[2] We are currently getting a heavy dose of this from Republicans as they try to avoid passing a pandemic rescue bill that will primarily benefit ordinary Americans. Here’s Senator Mike Enzi, from the metropolis of Wyoming, where he ran a shoe store, insisting that Social Security is the problem. Kelton has a story about Enzi. P. 41 et seq.

[3] The strange locution “defined benefit plan” comes from the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974. Its counterpart is defined contribution plans, which don’t promise any specific payment on retirement. It just requires the employer to pay a specific amount into some kind of plan with whatever vesting rights and investment possibilities the employer chooses.

[4] McDonnell-Douglas eventually merged with Boeing. Here’s a story connecting its executives to the 737 Max disaster.