Failing At Democracy

One of the reasons I read old books is that they help me understand the chaotic events of our current times. In The Public And Its Problems, John Dewey lays out a theory of the democratic state, and as we shall see, we are doing badly at it.

Recall that the public is a group of people who have common interests that need to be addressed, usually arising from the actions of other people. The public empowers certain of its members with the task of representing and protecting those interests. We call the aggregate of those people the state. [1]

The origins of the state.

This description implicitly separates “the state” from specific forms of government. Any reasonably large group of people has some form of government, and the bigger the group the more complex the government. In order for there to be a state, there must be a public.

It may be said that not until recently have publics been conscious that they were publics, so that it is absurd to speak of their organizing themselves to protect and secure their interests. Hence states are a recent development. Chapter 3, The Democratic State, p. 116.

One way to think about this is that the modern self-aware public evolved from prior traditional societies. The serfs in a feudal society generally do not see themselves as participants in government, but as fulfilling pre-ordained social roles.

What is a Democratic State?

Dewey likes this definition:

Democracy is a word of many meanings. … But one of the meanings is distinctly political, for it denotes a mode of government, a specified practice in selecting officials and regulating their conduct as officials. P. 121.

It’s not a soaring aspiration. It’s a functional description of what has to be done. The democratic state needs two things: 1) a system for the public to select its officials; and 2) a system for regulating the conduct of officials.

Selection of officials.

In the US, we elect a small group of officials, and they in turn select others for subsidiary roles. The public, all of us, are responsible for selecting officials who will represent our interests in conflicts with individuals or groups of people, as corporations and militias. The public may fail at its task by selecting people who use their position to enrich themselves and their cronies at the expense of the public or otherwise. Dewey says the crucial step is the selection of the right people. [2]

Regulating the Conduct of Officials.

The US Constitution provides two methods for regulating officials. These are impeachment, in the case of the executive and judicial branches, and expulsion, for the legislative branch. These are supplemented by rules that allow for sanctions short of removal, such as censure, and formal means for investigation through committees. There are statutes and formal regulations that constrain conduct of other officials, and many informal rules, now called norms. These laws and rules provide for sanctions.

The evolution of political democracy.

Political democratic states in Western Europe and North America evolved from older forms of government as the result of many small non-political developments. Dewey emphatically denies that these changes were driven by some overarching cause, such as an innate desire for democracy, or by dramatic changes in philosophical theories.

But theories of the nature of the individual and his rights, of freedom and authority, progress and order, liberty and law, of the common good and a general will, of democracy itself, did not produce the movement. They reflected it in thought; after they emerged, they entered into subsequent strivings and had practical effect. P. 123.

As an example, the ideas of John Locke were one of the theoretical sources for the Founding Fathers. His ideas are grounded in the rising economics of mercantilism, the attenuation of religious hegemony, and rising scientific understanding. He seems to be arguing against earlier thinkers grounded in earlier social, cultural, and intellectual structures. [3] Democracy was not the driving force of any of these changes. It emerged as a solution to the societal problems these non-political changes created.

Dewey doesn’t try to explain the entire evolution. He points to just two factors. First, the changes that led to democracy were driven by a fear of government and a desire to keep it to a minimum. This seems like a plausible reaction to an all-powerful monarchy, as existed in England and France, for example. Earlier governments were tied into other institutions, like the Church, and these too were feared or loathed. These institutions came to be seen as oppressive, not to groups of people but to individuals. There was already a growing tendency to think of the individual as the atomic unit. [4[ For Dewey, individualism was the result. [5]

The second important factor is the rise of science and technology. Over time it created changes in the nature of productive work and increased the range of consumer goods. People of all classes wanted more. The old rules became obstacles, and people began to question these rules and the system that produced them.

The old conception of Natural Law as the source of morality merged with the new idea that laissez-faire economics was a natural law in a synthesis that opposed artificial political laws. This led to the conclusion that government interference in property was bad, if not a moral evil, and the role of government should be little more than to protect property rights and personal integrity.

This is an overly simplified history, even more simplified by me, but it gives an idea of the genesis democracy as Dewey defines it. It leads to the conclusion that government officials are likely to be bad, so we should have short terms and serious control.

Problems arising from large organizations.

In earlier times, people’s primary relationships were face-to-face, family, friends, co-workers, church members, local people. The government was hardly relevant in day-to-day life. Its primary impact was taxes, the occasional war, and a few laws. By the time Dewey is writing, the primary relationships were impersonal, the individual was facing large corporate organizations in many aspects of life, including productive work. The state acted directly acted on individuals, touching their lives in many ways.

Group, or conjoint, action through business entities rivals the government in impact on individuals. Businesses “reach out to grasp the agencies of government;” not out of evil intent necessarily, but because they are the best organized groups of people. Even so, the power of these organizations has been controlled and directed by the state to some extent, and more is possible.

Discussion.

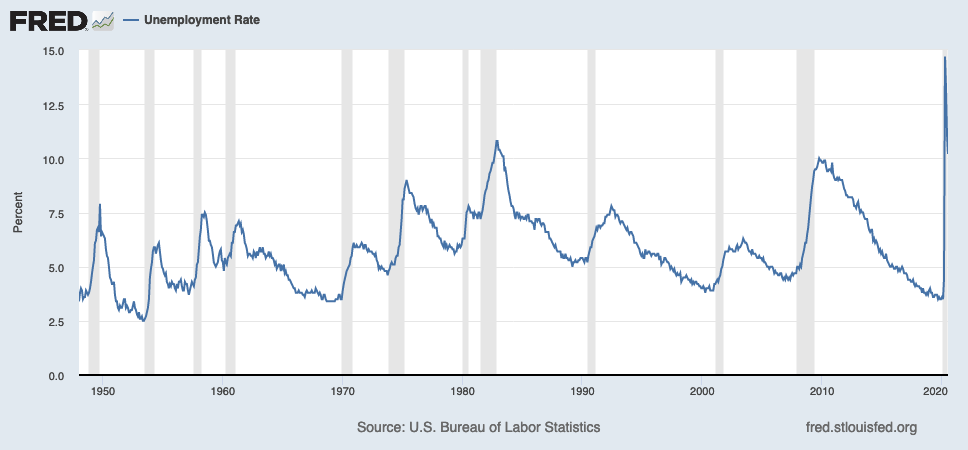

The second impeachment of Trump shows us that as a nation we have done badly at democracy. We elected unfit officials, people who are stupid, venal, conspiracy-ridden, power-maddened or a combination. Unfit legislators have for decades let the executive branch do monstrous things and refused to hold any of them accountable. The unfit people who staff our courts at all levels, but especially the unconstrained ideologues of SCOTUS have stymied legislative power, and have limited accountability of government and business elites with their pronouncements. Prosecutors are at fault as well, because they refuse even to investigate powerful private entities and their executives.

We fail democracy if we do not carry out our responsibility to regulate the conduct of our officials, and continue to select unfit people as our officials.

======

[1] I discuss these matter in detail in earlier posts, especially … and ….

[2] Dewey discusses different ways in which leaders were selected in earlier times, which I skip. It’s worth noting that we still elect people who met those irrelevant criteria: military and religious leaders, children of officials, charismatic people, and old white men. Pp. 117-9.

[3] I agree with Dewey about this, but it’s very far afield.

[4] Think of Descartes, sunk in self-contemplation. We also see it in Locke.

[5] Individualism lies at the heart of social contract theory and neoliberalism. Dewey rejects social contract theory.