Here’s my latest post from the Jeffrey Sterling trial at ExposeFacts.org, I describe how a top CIA officer — one who works in counterproliferation — used “curveball unironically,” even while presenting information that raised new concerns for me about Operation Merlin.

“Very often you get a curveball thrown at you.”

“Very often you get a curveball thrown at you.”

When Bob S, a longtime CIA operations manager working on Weapons of Mass Destruction described the ambiguity common on CIA operations as getting a “curveball” thrown at you in Wednesday’s testimony at the Jeffrey Sterling trial, he surely didn’t mean to reference the Iraqi fabricator who, under the pseudonym “Curveball,” lied about Saddam Hussein having mobile bioweapons labs, thereby playing a key role in CIA’s dodgy case to support the Iraq War.

Nevertheless, several people in the courtroom laughed that a senior CIA official working on WMD could ever use the term, Curveball, and not realize he was, at the same time, invoking one of CIA’s most embarrassing failures, one directly tied to Bob S’ work.

And while Bob S’ testimony made no mention of Iraq — at least not explicitly — his testimony did, at times, seem to confirm defense lawyer Edward MacMahon’s opening argument quip that the CIA was using this criminal case “to get its reputation back.” The better part of Wednesday’s testimony involved Bob S walking the court through one set of cables relating to the Merlin operation (though surely not all the ones pertaining to Zach W, the witness who lost his confidence when asked about Risen’s book on Tuesday), showing how slow and, the implication is, careful the operation was. At one point, as part of a very extended review of James Risen’s chapter on Operation Merlin stating which paragraphs Bob S claimed were true, which incorrect (though in some areas his claims about accuracy might be rebutted by the CIA cables), and which Bob S found to be “overstated,” the witness judged, “We have demonstrated that we did this very carefully.”

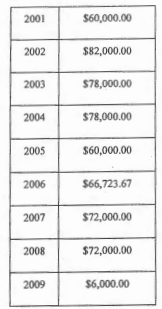

But even the timing of the operation raises questions about its efficacy. The CIA started this operation in summer 1996, at a time when (according to national lab scientist Walter C, who testified Wednesday) they believed Iran was a “nascent proliferator.” It took 9 months to reverse engineer a functional design from the intelligence a second Russian asset had provided, until April 1997. The national lab spent 8 months developing flaws and testing them, until late 1997. After that, a set of US experts “Red Teamed” the blueprints, looking for flaws; they only found 25% of the flaws but nevertheless were able to build something workable from the plans in 5 months, in May 1998. It then took over a year to get approval to use these things and get export control approval. There’s no reason to believe the Iranians could work as quickly as the US Red Team. Nevertheless, the US spent 3.5 years setting up the first offer for something that a Red Team was nevertheless able to use within 5 months.

Then there are really curious problems with the story, as told.

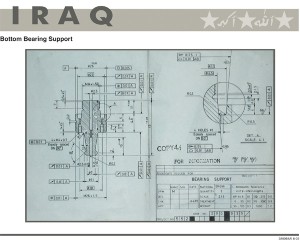

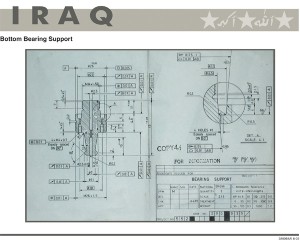

For example, according to Walter C and Bob S’ testimony, the CIA and national lab were very intent to build something that looked like a Russian schematic, complete with gaps in information that might arise from Russia’s compartmented nuclear development system (for some reason they had no concern that this would identify the other Russian asset involved in the operation, whose knowledge tracked that gap). In addition, purportedly, they were trying to hide that the Russian called Merlin at the trial — who had a post office box set up to correspond with potential targets, presumably in the US, and who emailed potential targets from the US — was in the US. In spite of both these details, however, they insisted on keeping the parts list — on what was supposed to be a Russian schematic reconstituted from a Russian lab — in English.

Under cross-examination Walter S admitted he had never seen a Russian schematic with English parts list. This led to a question from the defense about why the national lab had a Red Team whose sole job it was to find flaws in nuclear diagrams. “Why do you [meaning, presumably, the lab] have expertise in detecting flaws, all for deception?” The prosecution objected to this, the defense responded, “You opened the door,” but nevertheless Judge Brinkema sustained the objection after a lawyer’s conference. The CIA — or the nation’s weapons labs — have a system of Red Teams that test nuclear dodgy blueprints, but even though the government presented that information, the defense can’t force witnesses to explain why they have one.

The defense was more successful asking why the labs believed Iran had a fire-set program when, by 2007, the CIA judged (in a National Intelligence Estimate released to the public, though that was not explained to the jury) Iran had no nuclear weapons program. Expert Walter C said he was “only vaguely” aware of this assessment, which is rather incredible given the heated debate that ensued when the NIE judgement was released.

Within the context of the trial, perhaps this information didn’t raise real questions about what exactly the government believed it was doing (perhaps one of the plans was to give Iran a list of parts that intelligence agencies could then track the purchase of, which might be far easier to do if the parts are in the US). Perhaps all this (especially the unrebuttable claims about the accuracy of Risen’s reporting) is helping the CIA get its reputation back. But against the context of what else the public record shows CIA was doing at the time, it’s not clear how this restores CIA’s credibility on WMD.

For example, in late 2004, an officer also working in the counterproliferation division of CIA sued for wrongful termination, claiming that — starting in 2000 — his supervisors had ordered him to suppress intelligence because it conflicted with the Agency’s existing assessment of the country’s WMD program. While the earliest reporting on the suit — from none other than James Risen — made clear that some of this suppressed intelligence pertained to Iraq’s WMD program from the period leading up to the Iraq War, court documents filed after that 2007 NIE claim that the first report this former CIA officer’s supervisors asked him to suppress in 2000 pertained to Iran’s nuclear program, the same year as the Merlin operation.

Then there’s what has come to be known as the “laptop of death,” a laptop dealt to US intelligence in 2004 rather remarkably containing everything you’d need to claim Iran had a nuclear weapons program, including plans for a “detonation system.” Colin Powell rolled it out in 2004 as one of his last acts in the Bush Administration. Since then, the Iranians have been trying to prove it’s a fake, with increasing success of late. Nevertheless, that material has formed a significant part of the case supporting Iranian sanctions.

Finally, there’s another operation the CIA rolled out, in 2003, to “get its reputation back.” On June 25, 2003, on the evening before George Tenet had to testify to Congress about why the US had found no WMD in Iraq, CIA hailed the claims of an Iraqi nuclear scientist, Mahdi Obeidi, who claimed to have stashed a blueprint and working parts from an Iraqi centrifuge in a hole in his backyard since 1991. The story was riddled with internal contradictions, which didn’t stop Obeidi from having the almost unparalleled luck among Iraqi WMD scientists of settling in the vicinity of CIA headquarters. One of the oddest parts of Obeidi’s story is that the blueprints, purportedly developed in Iraq by Iraqis from German plans — which CIA briefly posted on its website, then took down — were in English.

On April 30, 2003, less than two months before CIA would roll out those nuclear blueprints in English (and at a time when US government officials were already working with Obeidi), Condoleezza Rice called New York Times‘ editors to the White House and persuaded them not to publish Risen’s story about Operation Merlin, in which (we now know) a Russian parts list rather curiously written in English were dealt to Iran back in 2000. Rice actually went further; she asked Times editor Jill Abramson to make Risen stop all reporting on this topic.

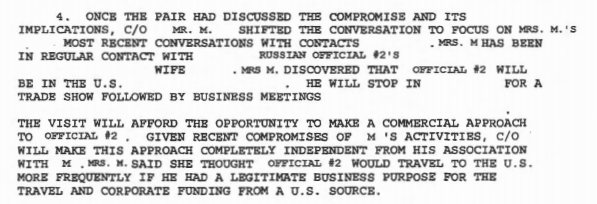

Which brings us to one more detail presented on Wednesday that may not actually help CIA get its reputation back. In 2011, the government hinted that the real problem with Risen’s story was that other US adversaries would learn that CIA was fronting a Russian scientist to deal them dodgy blueprints; Risen’s book does suggest the plan may have been used again. In testimony on Wednesday, Bob S confirmed that. This top counterproliferation official revealed that between 2001 and 2003, CIA had used the Russian dubbed Merlin to approach “other countries believed to be interested in WMD.” More troubling still, a March 11, 2003 cable introduced into evidence revealed that — after Iran had not taken the bait at all back in 2000 — CIA had started to try again with Merlin to reach out to Iran. In 2003, at a time when many worried an invasion of Iran would quickly follow the dodgy imminent invasion of Iraq, the CIA attempted to dump flawed nuclear blueprints into Iran’s hands via their asset, Merlin.

None of these other details will be presented to the jury, and even key details like the NIE judgment won’t come in as evidence with enough context for it to affect the jury’s deliberations in this case. But the way in which newly-revealed details about how Operation Merlin resonates with other dubious CIA claims made around the same time does present another likely motive, aside from the motive of revenge the government claims animated Sterling, to explain why leakers might go to James Risen in 2003 with concerns about the CIA operation.

In Risen’s affidavit to this court fighting his subpoena, he said he “made the decision to publish the information about Operation Merlin” because the case against Iraq “was based on flawed intelligence about Iraq’s non-existent weapons of mass destruction, including its supposed nuclear program.” He cited a 2005 report that “described American intelligence on Iran as inadequate to allow firm judgments about Iran’s weapons programs.” And he noted the “increasing speculation that the United States might be planning for a possible conflict with Iran, once again based on supposed intelligence concerning weapons of mass destruction.” Clearly, in Risen’s mind, this Iranian operation might tie into what he was learning and reporting about the Iraq debacle.

Again, none of this is likely to help Jeffrey Sterling. As Judge Leonie Brinkema noted yesterday, all the government has to do is prove Sterling is one of Risen’s sources, regardless of however many other sources he might have, motivated for whatever reason.

But the CIA seems to believe this tediously presented information helps it get its reputation back, helps explain the operation that appears so dubious in Risen’s book.

For listeners who know the full extent of CIA’s dodgy record on WMD, it does not.