Trump Prosecutions: Making Tea While Awaiting the Post-Election Flood

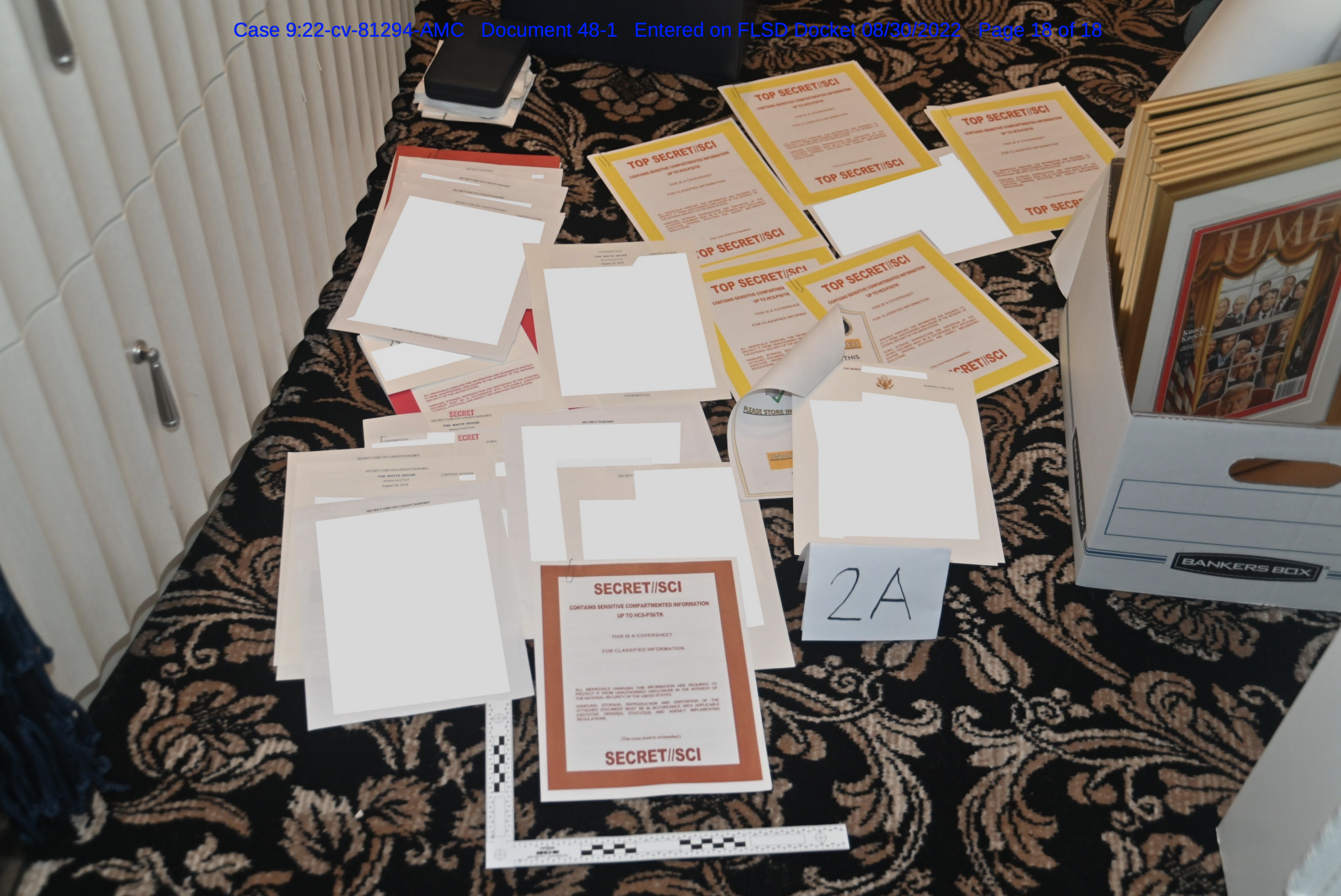

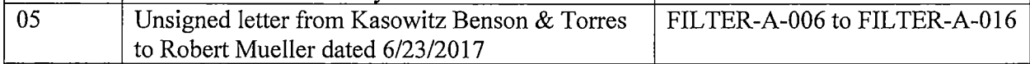

One of the only citations any of the filings in the Trump stolen document case make to prior 18 USC 793 prosecutions — one of the crimes under investigation — is this reference to a letter that then-NSA Director Mike Rogers submitted in the Nghia Pho case. It was cited to explain that sometimes the government has to kill sensitive intelligence programs based on the mere possibility they’ve been compromised. The letter also talked about how, when things get compromised by people bringing them home from work, US intelligence partners grow reluctant to share information. The letter was cited even though the letter itself was never docketed online (it was liberated at the time by Josh Gerstein).

In other words, someone knew to reference something really obscure to make a highly inflammatory argument about the ways that Trump has already done real harm to US national security.

One of the prosecutors in the Nghia Pho case was Thomas Windom, the MD-based AUSA brought in to lead the investigation into Trump’s attempts to steal the election.

Obviously, lots of people at DOJ’s National Security Division would also know that case, and so presumably the letter, well. I wrote about the important lessons DOJ seemed to take from the compromises that the Shadow Brokers leak (in part, that it doesn’t matter why someone brought classified documents home, they can do catastrophic damage to national security anyway). But I raise it here because of an assertion WaPo made when they broke the news that David Raskin — who prosecuted a number of terrorism cases that faced really difficult classification complications — was involved in some way in the stolen document case.

Just two weeks ago, Raskin won a guilty plea in a case with parallels to the Trump case — a former FBI analyst in Kansas City who authorities say took more than 300 classified files or documents to her home, including highly sensitive material about al-Qaeda and an associate of Osama bin Laden.

It’s actually unclear how much the case of Kendra Kingsbury resembles Trump’s. She was charged over three years after being fired from the FBI for the theft, charged with just Secret documents and only two counts of 18 USC 793e (supported by ten documents each), which made getting the plea far easier than charging her for any Top Secret documents or charging her for all twenty individually. According to the docket, the case never started the CIPA process. Her change of plea documents have not been docketed (and so don’t explain the five month delay in sentencing).

All of which is to say the Kingsbury prosecution, like the Pho one, avoided a lot of the difficulties a Trump case would pose, particularly given how unlikely it is that Trump would plead guilty. The Ahmed Ghailani, Zacarias Moussaui, and other early SDNY terror cases make far better precedents for the classification problems that a prosecution of Trump would pose.

Besides, as the WaPo reported, that’s not why Raskin was first brought to DC; he was brought there, like dozens of other prosecutors, to help with the flood of cases after January 6.

Justice Department officials initially contacted Raskin to consult on the criminal investigation into the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol. But his role has shifted over time to focus more on the investigation involving the former president’s possession and potential mishandling of classified documents, the people familiar with the matter said.

I raise all that because we’re beginning to get a whole bunch of new tea leaves in the various investigations into Trump.

CNN had a detailed report yesterday, describing that DOJ was prepping for post-election activity — as well as the likelihood that Trump will declare his candidacy for 2024 out of a belief it’ll shield him from indictment.

As it describes, in addition to Raskin, DOJ has brought on a former SDNY lawyer with extensive experience on conspiracy cases, David Rody, as well as added a high-ranking fraud and public corruption prosecutor and an appellate specialist, neither of whom they name.

Top Justice officials have looked to an old guard of former Southern District of New York prosecutors, bringing into the investigations Kansas City-based federal prosecutor and national security expert David Raskin, as well as David Rody, a prosecutor-turned-defense lawyer who previously specialized in gang and conspiracy cases and has worked extensively with government cooperators.

Rody, whose involvement has not been previously reported, left a lucrative partnership at the prestigious corporate defense firm Sidley Austin in recent weeks to become a senior counsel at DOJ in the criminal division in Washington, according to his LinkedIn profile and sources familiar with the move.

The team at the DC US Attorney’s Office handling the day-to-day work of the January 6 investigations is also growing – even while the office’s sedition cases against right-wing extremists go to trial.

A handful of other prosecutors have joined the January 6 investigations team, including a high-ranking fraud and public corruption prosecutor who has moved out of a supervisor position and onto the team, and a prosecutor with years of experience in criminal appellate work now involved in some of the grand jury activity.

CNN reports that DOJ is even considering whether to appoint a special counsel, though the implication seems to be that that would cover ongoing prosecutorial work, in the same way that John Durham was made a special counsel to shield his work from the snooping of outside oversight (which in Durham’s case led him to pursue ill-considered charges unsupported by his investigation).

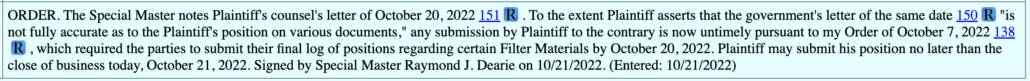

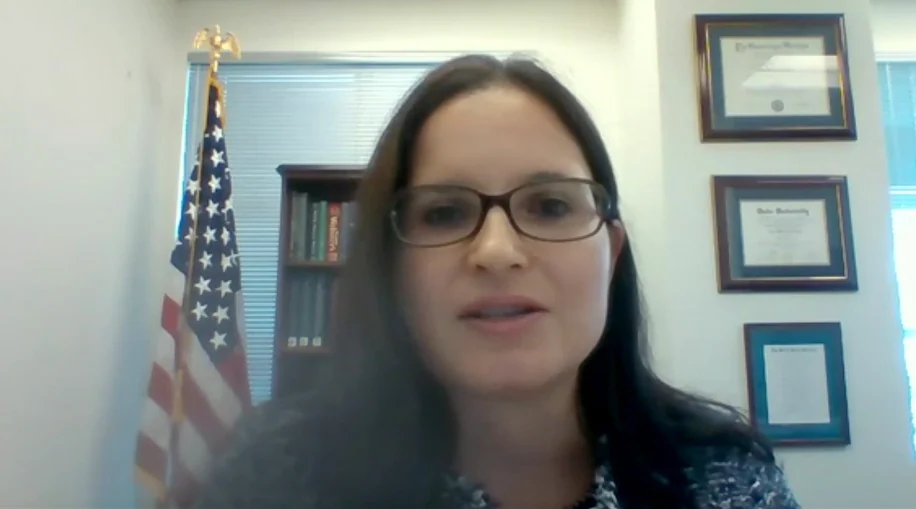

I expect as other outlets (especially ones with reporters that have more closely covered the January 6 investigation) will add clarity to all this. But given everything that’s happening, with the exception of the move of the public corruption prosecutor, it’s not clear how much these developments stem from resource allocations that have been a constant feature of the post-January 6 investigation, how much DOJ is putting together a prosecution team, or even whether DOJ has deliberately selected prosecutors (aside from the public corruption one) who weren’t at DC USAO when Billy Barr made all sorts of corrupt moves to help protect Trump. There are DC AUSAs on the team; Mary Dorhmann, who is sort of a Jill of All Prosecutorial Trades, is working with Windom even while she served on the team that won one guilty verdict and one hung verdict against Capitol Police cop Michael Riley and other more pedestrian January 6 cases.

All this is happening as DOJ just locked in Kash Patel’s testimony by compelling his testimony with use immunity. WaPo’s report describes that, in addition to asking him about his claims that Trump declassified documents, prosecutors also asked about Trump’s motive for stealing documents (whether classified or not).

National security prosecutors asked Patel about his public claims this spring that Trump had declassified a large number of government documents before leaving office in 2021. Patel was also questioned about how and why the departing president took secret and top-secret records to Mar-a-Lago,

This story is as useful for its account of former Deputy White House Counsel John Eisenberg’s testimony as for Patel’s; he’s the guy who attempted to bury the Perfect Transcript of Trump’s call with Volodymyr Zelenskyy (remember that witnesses friendly to the subject of an investigation often share their testimony to help others, effectively a way to coordinate stories).

Finally, NYT reported something I’ve been expecting for some time: Trump lawyers are getting fed up with the incompetent advice of Boris Epshteyn, who is not a defense attorney but who claims to be playing a key role in Trump’s defense.

A tirade of a lawsuit that Donald J. Trump filed on Wednesday against one of his chief antagonists, the New York attorney general, was hotly opposed by several of his longstanding legal advisers, who attempted an intervention hours before it was submitted to a court.

Those opposed to the suit told the Florida attorneys who drafted it that it was frivolous and would fail, according to people with knowledge of the matter. The loudest objection came from the general counsel of Mr. Trump’s real estate business, who warned that the Floridians might be committing malpractice.

Nonetheless, the suit was filed.

[snip]

The new 41-page lawsuit against Ms. James was filed in Palm Beach by Timothy W. Weber, Jeremy D. Bailie and R. Quincy Bird, members of a St. Petersburg-based law firm — and was championed by Boris Epshteyn, an in-house counsel for the former president who has become one of his most trusted advisers.

[snip]

Unable to persuade the Florida lawyers to stand down Wednesday, the Trump Organization’s general counsel, Alan Garten, then took aim at Mr. Epshteyn, blaming him in an email to Mr. Epshteyn and other lawyers for the filing of the suit, said the people with knowledge of the discussion. Frustrations with Mr. Epshteyn among some of Mr. Trump’s other aides and representatives have been brewing for months and boiled over with the new legal action.

Another lawyer for Mr. Trump, Christopher M. Kise, a former Florida solicitor general, also objected to the filing of the lawsuit on Wednesday. And Mr. Trump’s legal team in New York expressed concern that the Florida lawsuit would undermine their defense in Ms. James’s case, costing them credibility with both the New York attorney general’s office and the judge overseeing the case, the people with knowledge of the matter said.

It’s fairly astonishing that someone as notoriously paranoid as Trump has not yet begun to wonder whether Epshteyn has Trump’s own interests in mind. Certainly I’ve questioned it.

But pissing off Alan Garten, especially — really one of the only stable legal presences in Trump’s life over the last six years — will not bode well for Trump going forward.

None of these details (not even the shift of the public corruption prosecutor, which I think is one of the more important developments) tell us where a Trump prosecution will start to move next week, after the election. Given all the factors — especially the resource allocations on account of the January 6 investigation and conflicts that may have been created by Trump’s past corruption — it will be impossible for anyone to understand where this is headed for some time.

But the tea leaves have finally convinced the TV lawyers that it is headed, somewhere.