DOJ Arresting Their Way to Clarity on Joe Biggs’ Two Breaches of the Capitol

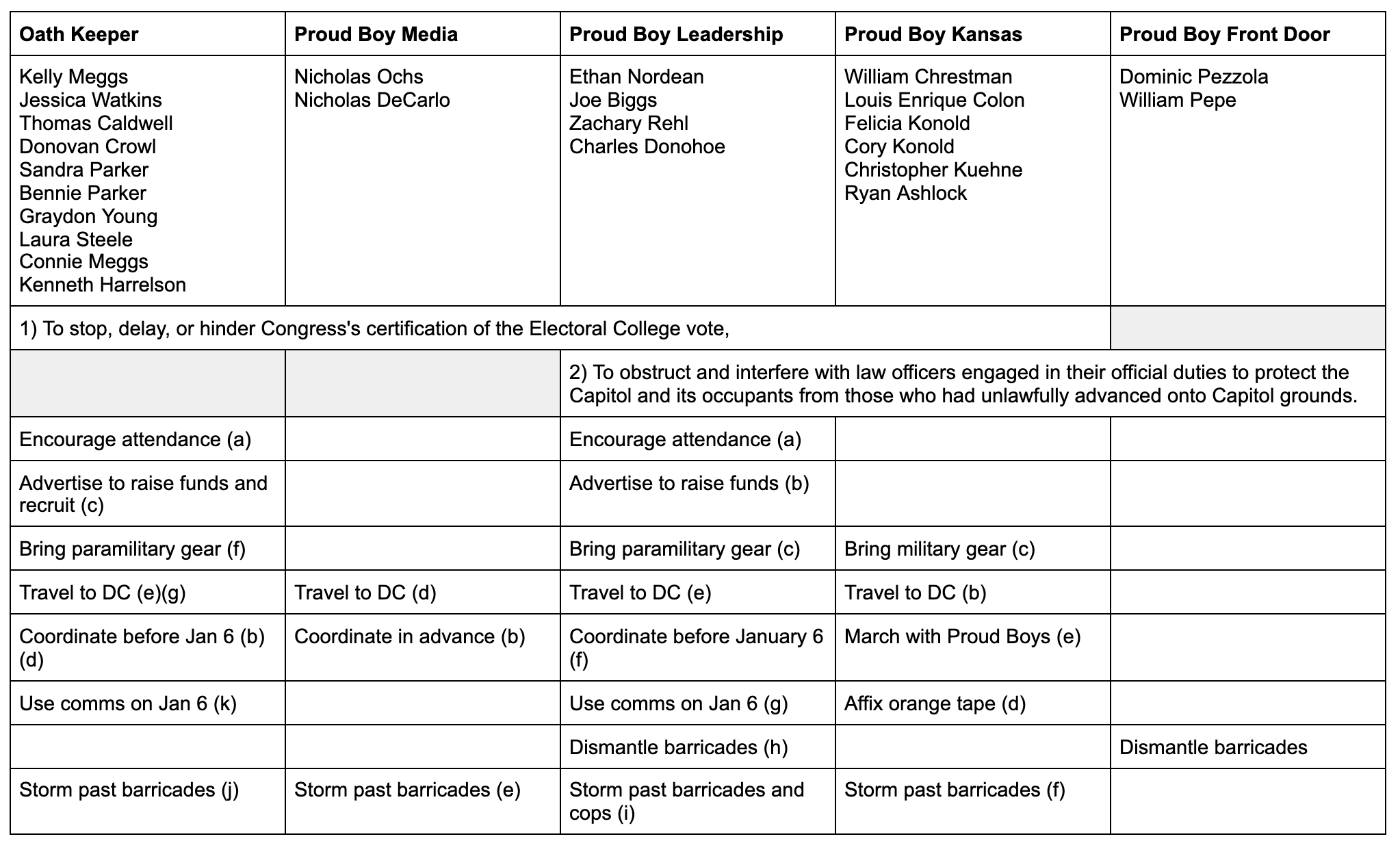

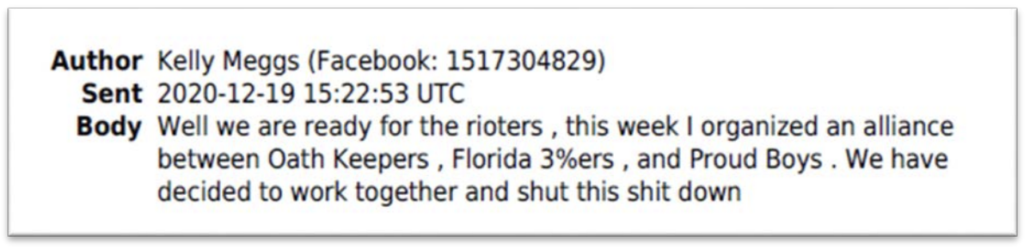

The Proud Boys Leadership conspiracy indictment describes that Joe Biggs breached the Capitol twice.

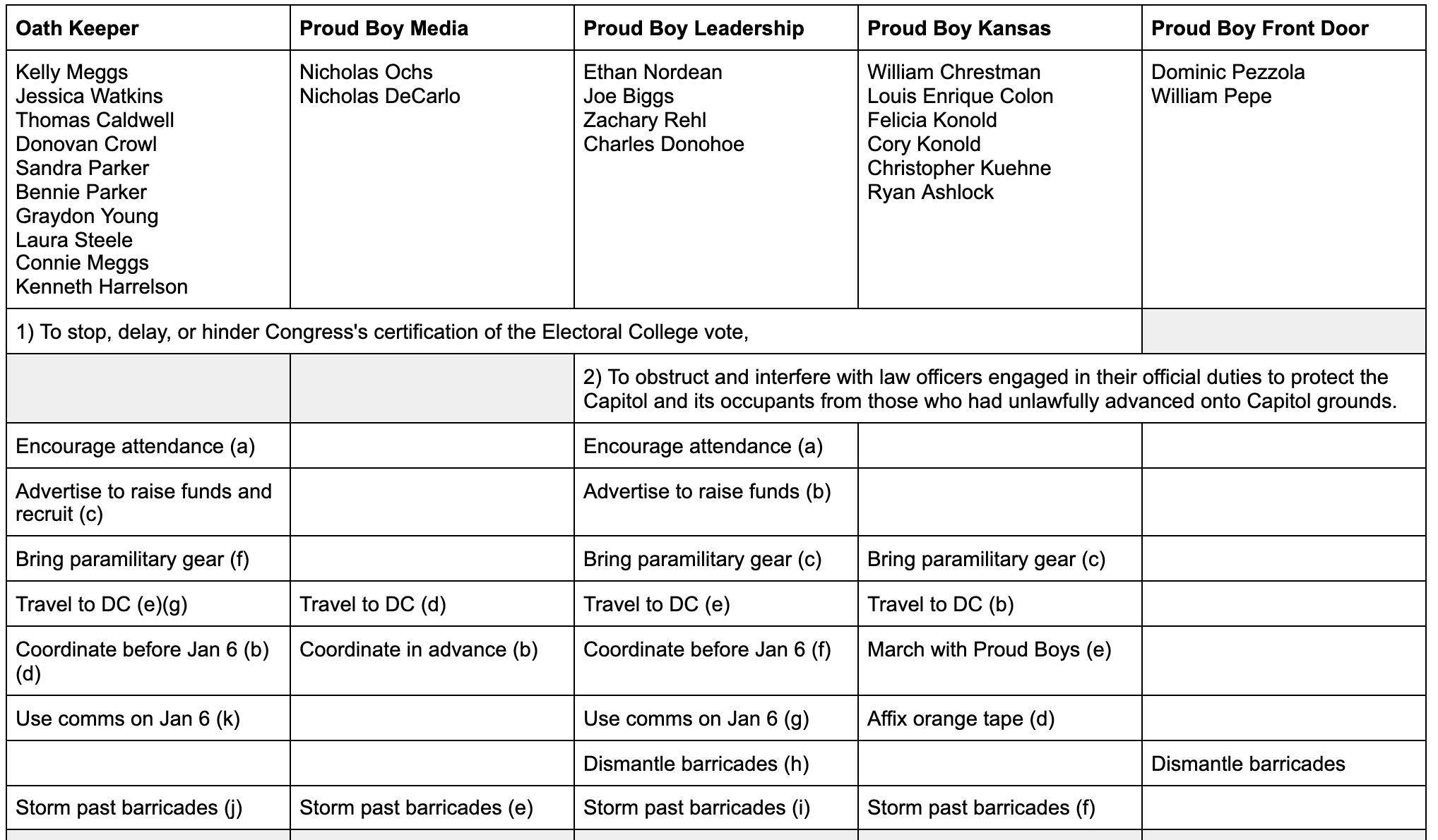

He entered first on the west side through a door opened after Dominic Pezzola broke through an adjacent window with a riot shield.

At 2:14 p.m., BIGGS entered the Capitol building through a door on the northwest side. The door was opened after a Proud Boys member, Dominic Pezzola, charged elsewhere, used a riot shield at 2:13 p.m. to break window allowed rioters to enter the building and force open an adjacent door from the inside. BIGGS and Proud Boys members Gilbert Garcia, William Pepe, and Joshua Pruitt, each of whom are charged elsewhere, entered the same door within two minutes of its opening. At 2:19 p.m., a member of the Boots on the Ground channel posted, “We just stormed the capitol.”

Then, Biggs left the building, walked around it, took a selfie from the east side, then forced his way in the east side and headed from there to the Senate.

BIGGS subsequently exited the Capitol, and BIGGS and several Proud Boys posed for a picture at the top of the steps on the east side of the Capitol.

Thirty minutes after first entering the Capitol on the west side, BIGGS and two other members of the Proud boys, among others, forcibly re-entered the Capitol through the Columbus Doors on the east side of the Capitol, pushing past at least one law enforcement officer and entering the Capitol directly in front of a group of individuals affiliated with the Oath Keepers. [my emphasis]

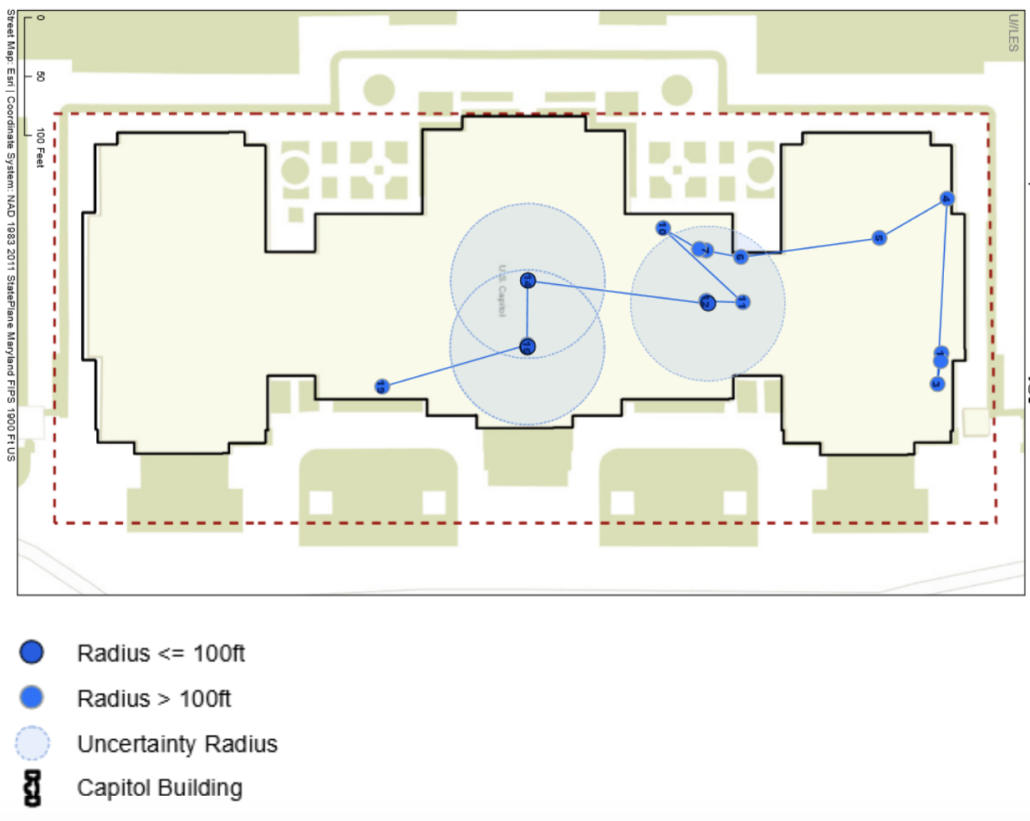

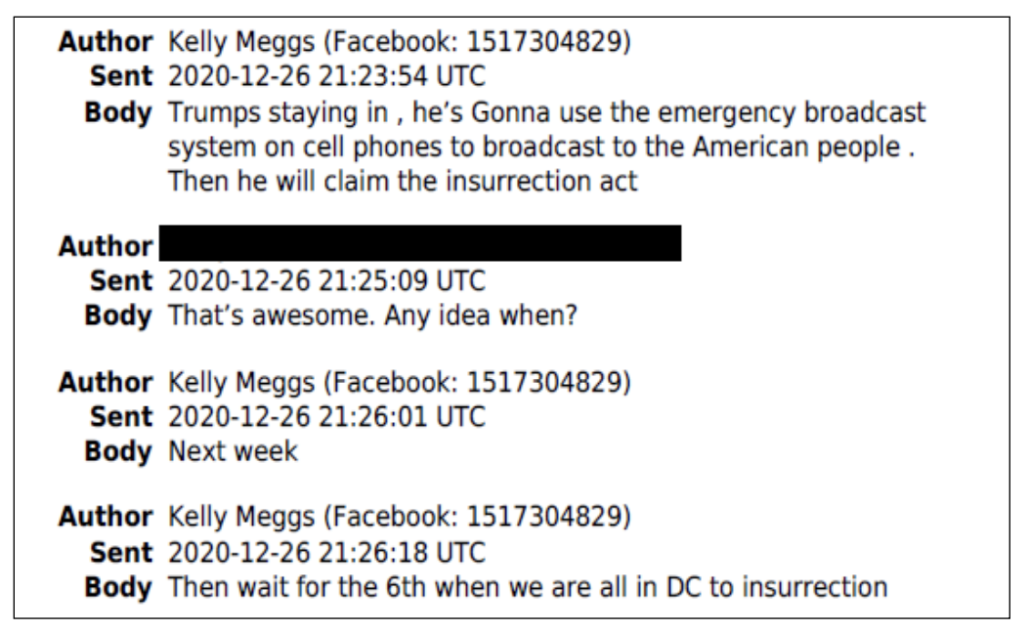

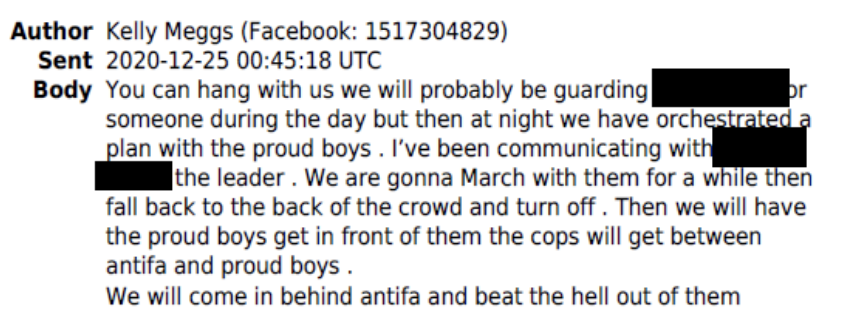

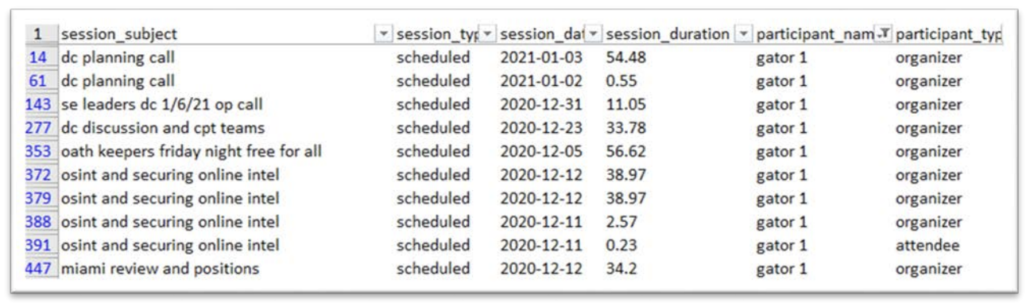

Understanding Biggs’ actions — including whether they were coordinated with the Oath Keepers who entered at virtually the same time as him (including fellow Floridian Kelly Meggs, who had just “organized an alliance” with the Proud Boys in December) — is crucial to understanding the insurrection as a whole.

That’s particularly true given that Biggs re-entered the Capitol and headed to the Senate, where Mike Pence had only recently been evacuated. That’s also true given how Biggs’ actions coincide so neatly with those of the Oath Keepers.

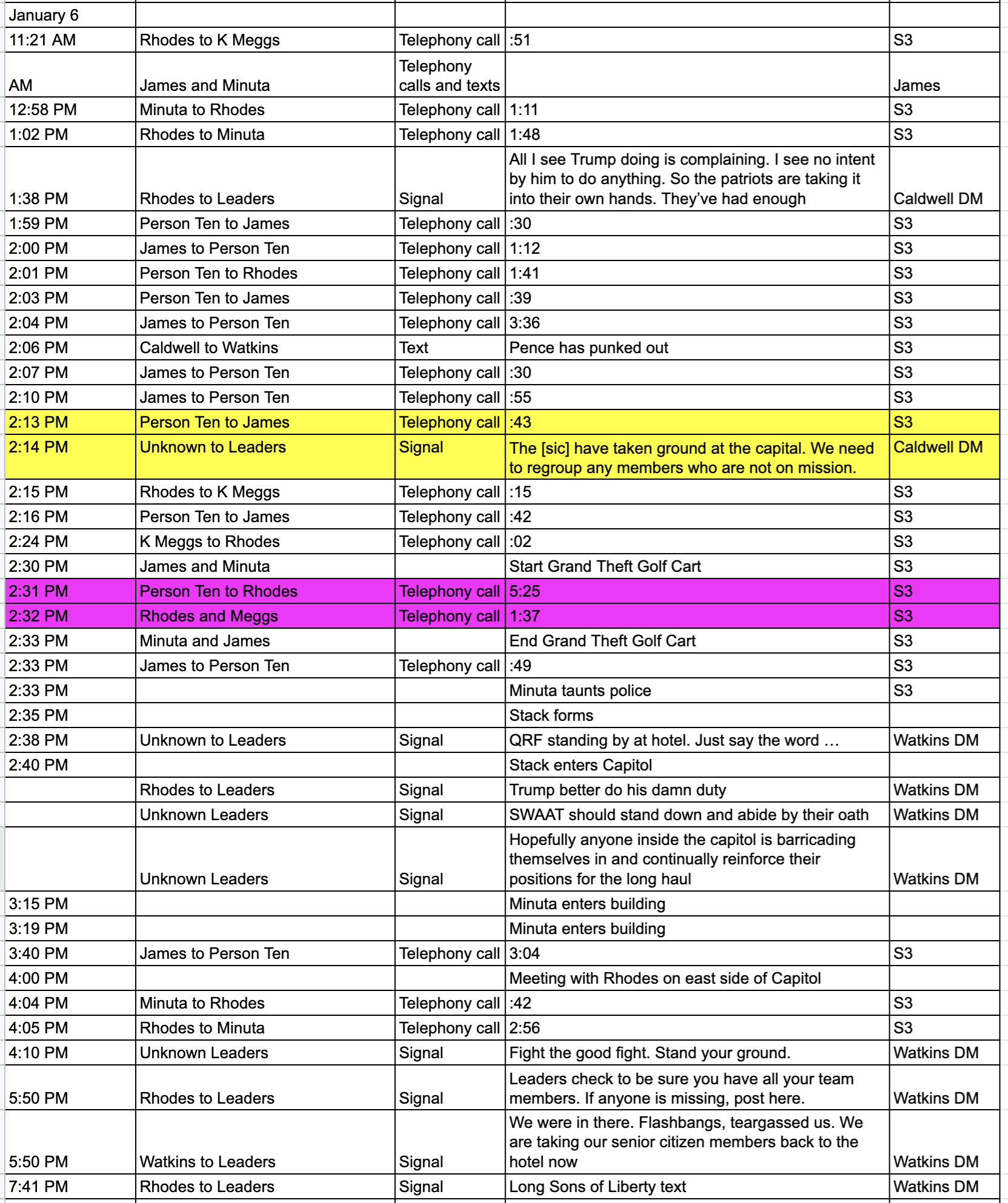

At the moment Pezzola breaks the Capitol window with a shield, Person Ten contacts Joshua James (from Alabama but seemingly affiliated with the Florida Oath Keepers). At the moment Biggs enters the Capitol, someone on the Oath Keepers’ Signal channel informed the list that “The[y] have taken ground at the capital [sic]. We need to regroup any members who are not on mission.” This is a quicker response than the Proud Boys Boots on the Ground channel itself had to the initial breach.

And that’s what happened. Both the Oath Keepers and the Proud Boys regrouped and opened a new front on the assault on the Capitol.

Rhodes called Kelly Meggs. Person Ten called James. Then Rhodes had overlapping phone calls with Person Ten and Meggs. Around that time, The Stack started making their way to an entry of the Capitol on the other side of the building from where they were. And James and Minuta hopped in some golf carts and rushed to the Capitol (I’m not sure from where). During the period when The Stack, commanded by Kelly Meggs, was making their way to the Capitol and Biggs was walking around rather than through it, Roberto Minuta arrived and started harassing the cops guarding the door through which Biggs and The Stack would shortly enter, perhaps ensuring that the cops remained at their post rather than reinforcing the east side.

I had speculated here that Proud Boys in the initial breach — most notably former Army Captain Gabriel Garcia — were live streaming with the intent of providing tactical information to people located remotely who were performing a command and control function.

If you were following Garcia’s livestreams in real time — even from a remote location — you would have visibility on what was going on inside almost immediately after the first group of the Proud Boys breached the Capitol.

In a later livestream, Garcia narrated what happened in the minutes after the Proud Boys had breached the Capitol.

GARCIA states, “We just went ahead and stormed the Capitol. It’s about to get ugly.” Around him, a large crowd chants, “Our house!”

Then, as a standoff with some cops ensued, Garcia filmed himself describing, tactically, what was happening, and also making suggestions to escalate violence that were heeded by those around him.

At minute 1:34, a man tries to run through the line of USCP officers. The officers respond with force, which prompts GARCIA to shout, “You fucking traitors! You fucking traitors! Fuck you!” As the USCP officers try to maintain positive control of the man that just rushed the police line, GARCIA yells, “grab him!” seemingly instructing the individuals around him to retrieve the man from USCP officers. GARCIA is holding a large American flag, which he drops into the skirmish in an apparent attempt to assist the individuals who are struggling with the USCP officers.

USCP officers maintain control of the line, holding out their arms to keep the crowd from advancing. At least one USCP officer deploys an asp. GARCIA turns the camera on himself and offers tactical observations regarding the standoff. [my emphasis]

Garcia’s livestream was such that you would obtain crowd size estimates from it, as well as specific names of officers on the front line, as well as instructions to “keep ’em coming,” seemingly asking for more bodies for this confrontation.

At minute 3:26, GARCIA, who is still in extremely close proximity to the USCP officer line again yells, “Fucking traitors!” He then joins the crowd chanting “Our house!” At minute 3:38, GARCIA states, “You ain’t stopping a million of us.” He then turns the camera to the crowd behind him and says, “Keep ‘em coming. Keep ‘em coming. Storm this shit.” GARCIA chants with the crowd, “USA!”

Soon after, GARCIA stops chanting and begins speaking off camera with someone near him. At minute 4:28, GARCIA says, “do you want water?” Though unclear, GARCIA seems to be asking the person with whom he is speaking. GARCIA is so close to an officer that, as the camera shifts, the only images captured are those of the officer’s chest and badge. [my emphasis]

Remarkably, Garcia filmed himself successfully ordering the rioters to hold the line — which they do — and then filmed them charging the police.

GARCIA yells, “Back up! Hold the line!” Shortly thereafter, the crowd begins advancing, breaching the USCP officer line. GARCIA says, “Stop pushing.” The last moments captured in the video are of the crowd rushing the USCP officers.

A filing arguing for detention for Ethan Nordean confirms that Proud Boys located offsite were monitoring the livestream and providing instructions.

When the Defendant, his co-Defendants, and the Proud Boys under the Defendant’s command did, in fact, storm the Capitol grounds, messages on Telegram immediately reflected the event. PERSON-2 announced, “Storming the capital building right now!!” and then “Get there.” [Un-indicted co-conspirator-1] immediately followed by posting the message, “Storming the capital building right now!!” four consecutive times.6 These messages reflect that the men involved in the planning understood that the plan included storming the Capitol grounds. This shared understanding of the plan is further reflected in co-Defendant Biggs’ real-time descriptions that “we’ve just taken the Capitol” and “we just stormed the fucking Capitol.”

6 UCC-1 and PERSON-2 are not believed to have been present on the Capitol grounds, but rather indicated that they were monitoring events remotely using livestreams and other methods.*

So at least on the Proud Boys side, there was this kind of command and control.

And the government has been arresting their way to some clarity on this point.

Sometime before March 1, the government got access to both the leadership Telegram channel the Proud Boys used to coordinate the insurrection and the “Boots on the Ground” channel, meaning they’ve got monikers for around 35 active Proud Boy participants in the insurrection who have not yet been arrested. In the weeks since the Biggs and Nordean conspiracy indictment disclosed that the government had these chats, the government has arrested several people with ties to one or another of these men (though without saying whether they identified them from the Boots on the Ground channel or whether they arrested them at this time for investigative reasons).

Two of these men just happen to be two of Joe Biggs’ co-travelers the day of the insurrection, Paul Rae and Arthur Jackman, both also from Florida. The complaints for both are very similar, possibly written by the same FBI agent. Both complaints go through the greatest hits of the Proud Boy actions that day, listing all the conspiracies already charged. While the affidavits include the testimony of acquaintances of both men (in Jackman’s case, obtained after a January 19 interview with Jackman himself, meaning that testimony couldn’t be the lead via which they IDed him), the affidavits also focus on their entries with Joe Biggs, with Rae entering the west Capitol door right next to Biggs.

And Jackman walking up steps with his hand on Biggs’ shoulder.

Each affidavit includes the photo obtained from warrants served on Biggs showing the selfie mentioned in the Leader indictment (bolded above).

In Rae’s affidavit, they’ve redacted out all but his face and Biggs’.

They use the same approach in Jackman’s affidavit, redacting the others (including Rae, who had already been arrested).

If I were one of the two other guys in this picture, I’d be arranging legal representation right now.

The affidavits show both men entering the Capitol on the east side, along with Biggs. As he did on the west side, Rae walked in beside Biggs (you can see Jackman just ahead of Rae in this picture).

And as he did elsewhere in the Capitol, Jackman walked with his hand on Biggs’ shoulder.

Jackman’s affidavit shows him in the Senate (where we know Biggs also went).

The government arrested Rae on March 24. They arrested Jackman on March 30. Again, I’d be pretty nervous if I were one of the other two guys.

Because if the government can show that this second breach by Biggs was coordinated with the Oath Keepers, with The Stack led by the guy who arranged an alliance in December, Kelly Meggs, it will make these five separate conspiracies mighty cozy (in any case, the government is already starting to refer to the multiple Proud Boys conspiracies as one).

There’s at least one other action on which both militias may have coordinated: aborted efforts to launch a second wave after 4PM, something that Rudy Giuliani seems to have had insight into.

But for now, the government seems pretty focused on arresting their way to clarity about why Joe Biggs breached the Capitol, then walked outside and around it, and then breached it again.

* I had suggested in this post that UCC-1 might be Nicholas Ochs. But that’s not possible, because the government knows he was onsite. Moreover, the government is now treating defendants in one of the Proud Boys conspiracy indictments (most notably Dominic Pezzola) as co-conspirators with those charged in other conspiracy indictments (including Nordean), so Ochs would be an indicted co-conspirator. Another — far more intriguing possibility — is that it is James Sullivan (who might have a leadership role in Utah’s Proud Boys), who was in contact with Rudy Giuliani about the insurrection, and who inexplicably hasn’t been arrested. Certainly, Rudy seems to have had the information available on those chats in real time.

Pezzola

Pezzola