Cautions on ABC’s Huge Mark Meadows Scoop

For more than six months, access journalists in DC have been trying to confirm how much Mark Meadows cooperated with Jack Smith.

Today, ABC has a huge scoop reporting that Meadows testified at least three times, one time — before a grand jury — with immunity.

Former President Donald Trump’s final chief of staff in the White House, Mark Meadows, has spoken with special counsel Jack Smith’s team at least three times this year, including once before a federal grand jury, which came only after Smith granted Meadows immunity to testify under oath, according to sources familiar with the matter.

Click through to read the details — ABC has earned the clicks.

But I caution against concluding too much about what the testimony means. Most importantly, there’s no hint that Meadows has flipped. Meadows has testified (which a past ABC scoop made clear). But giving immunized testimony is not flipping, and the two ABC stories raise far more questions about the story Meadows has told.

I say that for several reasons. First, ABC doesn’t describe the dates for any of his interviews. I’ll return to that, but it’s important that ABC doesn’t reveal whether Meadows’ testimony to Jack Smith precedes or postdates the Georgia indictment and subsequent failure to get the Georgia indictment removed to Federal courts. An earlier big ABC scoop describes April grand jury testimony, and it’s not clear that this would be a different time frame or grand jury appearance.

I offer cautions, as well, because virtually all of ABC’s reporting says that Meadows was asked not about what Trump did on a given day, but whether Meadows believed what Meadows had said publicly. Here’s an example.

Sources told ABC News that Smith’s investigators were keenly interested in questioning Meadows about election-related conversations he had with Trump during his final months in office, and whether Meadows actually believed some of the claims he included in a book he published after Trump left office — a book that promised to “correct the record” on Trump.

Again, click through to see how much of the rest is of the same sort.

As I noted in my post on that prior big ABC scoop, there are still loads of details — especially about January 6 — missing from the public timeline that Meadows surely knows.

There’s a lot that’s missing here — most notably Meadows’ coordination with Congress and any efforts to coordinate with Mike Flynn and Roger Stone’s efforts more closely tied to the insurrection and abandoned efforts to deploy the National Guard to protect Trump’s mob as it walked to congress. Unless those actions get added to charges quickly, Meadows will be able to argue, in Georgia, that his actions complied with federal law without having to address them. If and when they do get charged in DC, I’m sure Meadows’ attorneys hope, his criminal exposure in Georgia will be resolved.

Importantly, that earlier ABC scoop served to signal co-conspirators how Meadows changed his testimony after prosecutors obtained proof his claims about his ghost-writers — the same ghost-writers whose book remains at the center of ABC’s scoop! — were proven wrong by further evidence.

That story suggested Meadows was only going to be as truthful as evidence presented to him required him to be.

And this story is of the same type. It describes how, as he did in the stolen documents case, Meadows said he didn’t believe what he wrote when it was legally necessary.

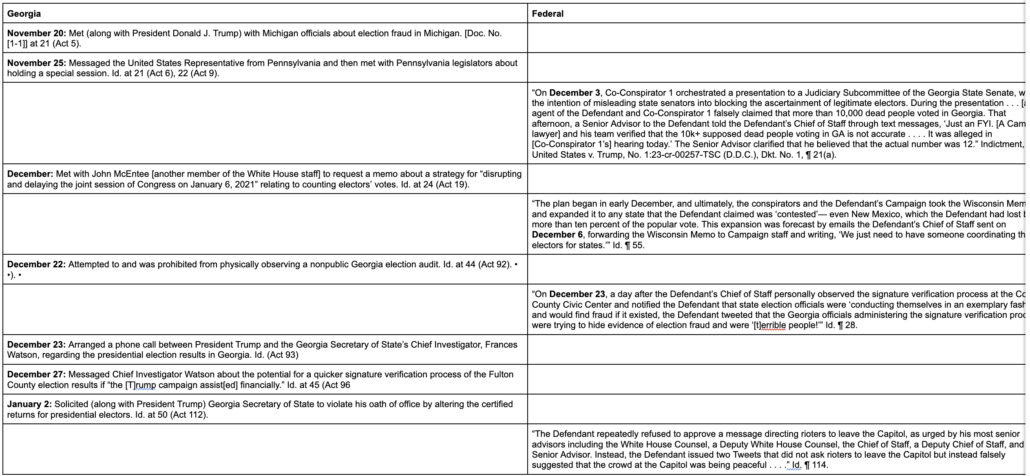

Finally, that post also lays out that the narrative told in the DC indictment, while useful for Jack Smith, is different than the narrative told by Fani Willis, where Mark Meadows has not given cooperative testimony. The right column (his story to Jack Smith) in this table is helpful for Jack Smith, but probably not true; the left column (where he didn’t cooperate) is more damning.

Meadows team recites the alleged Georgia acts as Judge Jones has characterized them on page 19 and then directly quotes the references to Meadows in the federal indictment on page 26. It helps to read them a table together:

There’s an arc here. The early acts in both indictments might be deemed legal information gathering. After that, in early December, Meadows takes two actions, one alleged in Georgia and the other federally, both of which put him clearly in the role of a conspirator, neither of which explicitly involves Trump as charged in the Georgia indictment. Meadows:

- Asks Johnny McEntee for a memo on how to obstruct the vote certification

- Orders the campaign to ensure someone is coordinating the fake electors

The events on December 22 and 23, across the two indictments, are telling. Meadows flies to Georgia and, per the Georgia indictment, attempts to but fails to access restricted areas. Then he flies back to DC and, per the federal indictment, tells Trump everything is being done diligently. Then Meadows arranges and participates in another call. Both in a tweet on December 22 and a call on December 23, Trump pressures Georgia officials again. For DOJ’s purposes, the Tweet is going to be more important, whereas for Georgia’s purposes, the call is more important. But with regards his argument for removal and dismissal, Meadows would argue that he used his close access to advise Trump that Georgia was proceeding diligently.

On December 27, Meadows calls and offers to use campaign funds to ensure the signature validation is done by January 6. This was not Meadows arranging a call so Trump could make the offer himself, it was Meadows doing it himself, likely on behalf of Trump, doing something for the campaign, not the country.

On January 2, Meadows participates in the Raffensperger call, first setting it up then intervening to try to find agreement, but then ultimately pressuring state officials not so much to just give Trump the votes he needs, which was Trump’s ask, but to turn over state data.

Meadows: Mr. President. This is Mark. It sounds like we’ve got two different sides agreeing that we can look at these areas ands I assume that we can do that within the next 24 to 48 hours to go ahead and get that reconciled so that we can look at the two claims and making sure that we get the access to the secretary of state’s data to either validate or invalidate the claims that have been made. Is that correct?

Germany: No, that’s not what I said. I’m happy to have our lawyers sit down with Kurt and the lawyers on that side and explain to my him, here’s, based on what we’ve looked at so far, here’s how we know this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong, this is wrong.

Meadows: So what you’re saying, Ryan, let me let me make sure … so what you’re saying is you really don’t want to give access to the data. You just want to make another case on why the lawsuit is wrong?

Meadows was pressuring a Georgia official, sure, but to do something other than what Trump was pressuring Raffensperger to do. His single lie (he was charged for lying on the call separately from the RICO charge), one Willis might prove by pointing to the overt act from the federal indictment on December 3, when Jason Miller told Meadows that the number of dead voters was not 10,000, but twelve, is his promise that Georgia’s investigation has not found all the dead voters.

I can tell you say they were only two dead people who would vote. I can promise you there were more than that. And that may be what your investigation shows, but I can promise you there were more than that.

But even there, two is not twelve. Meadows will be able to challenge the claim that he lied, as opposed to facilitated, as Chief of Staff, Trump’s lies.

Finally, in an overt act not included in the Georgia indictment, Meadows is among the people on January 6 who (the federal indictment alleges) attempted to convince Trump to call off the mob.

There’s a lot that’s missing here — most notably Meadows’ coordination with Congress and any efforts to coordinate with Mike Flynn and Roger Stone’s efforts more closely tied to the insurrection and abandoned efforts to deploy the National Guard to protect Trump’s mob as it walked to congress. Unless those actions get added to charges quickly, Meadows will be able to argue, in Georgia, that his actions complied with federal law without having to address them. If and when they do get charged in DC, I’m sure Meadows’ attorneys hope, his criminal exposure in Georgia will be resolved.

Of what’s included here, those early December actions — the instruction to Johnny McEntee to find some way to obstruct the January 6 vote certification and the order that someone coordinate fake electors — are most damning. That, plus the offer to use campaign funds to accelerate the signature match, all involve doing campaign work in his role as Chief of Staff. For the federal actions, Jack Smith might just slap Meadows with a Hatch Act charge and end the removal question — but that might not help him, Jack Smith, make his case, because several parts of his indictment rely on exchanges Meadows had privately with Trump, and Meadows is a better witness if he hasn’t been charged with a crime.

Aside from those, Meadows might argue — indeed, his lawyers may well have argued to Jack Smith to avoid being named as a co-conspirator — that his efforts consistently entailed collecting data which he used to try to persuade the then-President, using his access as a close advisor, to adopt other methods to pursue his electoral challenges. Meadows’ lawyers may well have argued that several things marked his affirmative effort to leave the federally-charged conspiracies. In this removal proceeding, I expect Meadows will argue that his actions on the Raffensperger call were an attempt, like several others, to collect more data to use his close access as an advisor to better persuade the then-President to drop the means by which he was challenging the vote outcome.

The point being, that before Fani Willis indicted Mark Meadows, Meadows had found a story that was going to work. And now, that story doesn’t work anymore.

Which is why the timing of Meadows’ immunized testimony to a grand jury and the timing of this scoop matters. His January 6 testimony seems to conflict with what Willis knows. This paragraph, from today’s big ABC scoop, is even less credible than stuff in the indictments.

However, according to what Meadows told investigators, Trump seemed to grow increasingly concerned as he learned more about what was transpiring at the Capitol, and Trump was visibly shaken when he heard that someone had been shot there, sources said.

If the two versions of Meadows story have started to obviously conflict, he’s may be doing some soul searching about whether he wants to go the way of Sidney Powell and Ken Chesebro and Jenna Ellis, who sent 350 texts with Meadows.

And before he does that soul searching, he’s going to want to signal to others what he has said, to test how valuable it is for him to continue to say it.