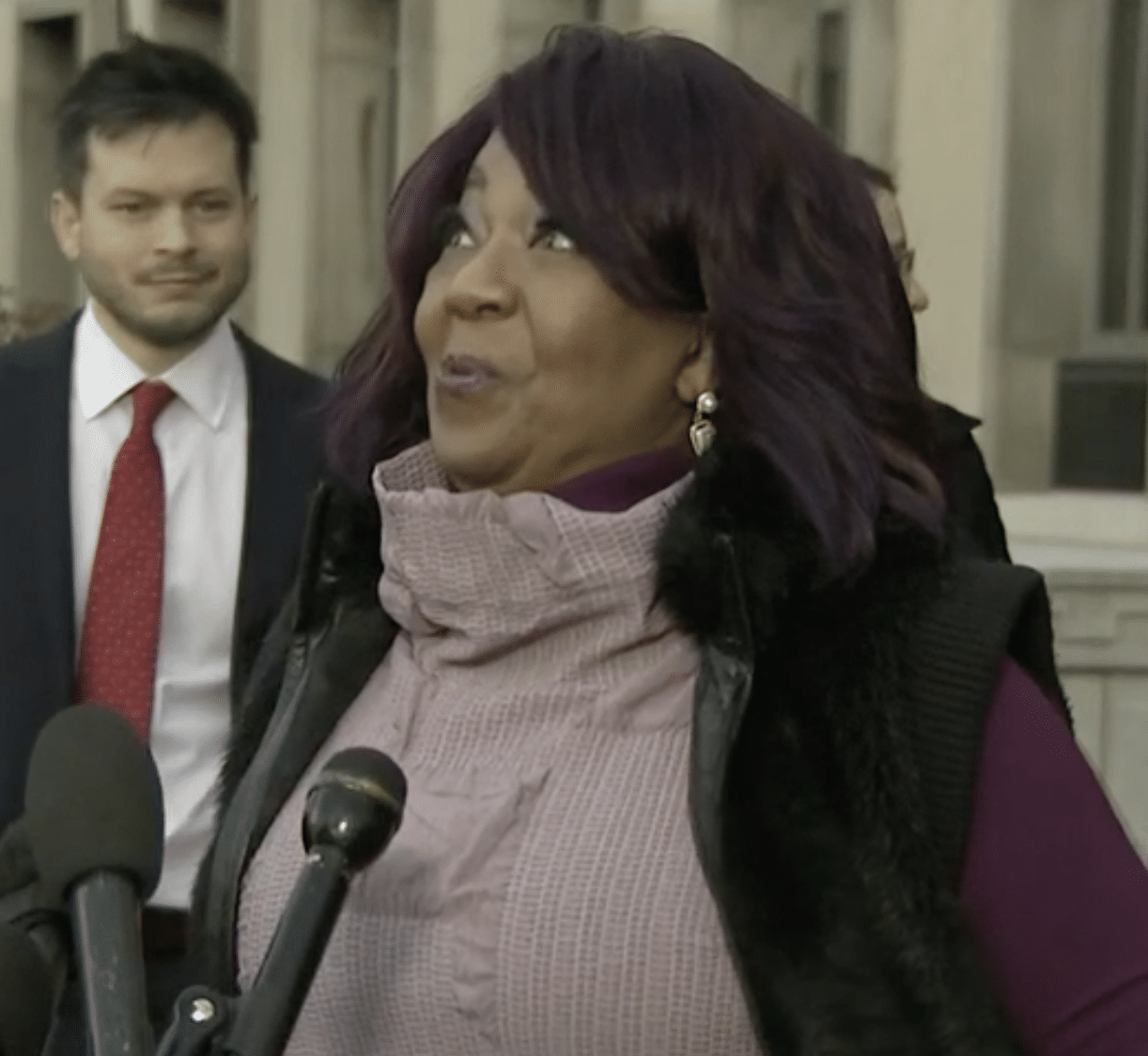

After a jury awarded Ruby Freeman and her daughter $148 million for the intentional lies the former president’s former lawyer told about them in an attempt to steal an election, this is some of what Freeman had to say:

Good evening everyone. I am Lady Ruby. Today’s a good day. A jury stood witness to what Rudy Giuliani did to me and my daughter and held him accountable. And for that I’m thankful. Today is not the end of the road. We still have work to do. Rudy Giuliani was not the only one who spread lies about us, and others must be held accountable too. But that is tomorrow’s work. For now, I want people to understand this. Money will never solve all of my problems. I can never move back to the house that I called home. I will always have to be careful about where I go and who I choose to share my name with. I miss my home, I miss my neighbors, and I miss my name.

Freeman’s daughter, Shaye Moss, said this:

As we move forward, and continue to seek justice, our greatest wish is that no one — no election worker, or voter, or school board member, or anyone else — ever experiences anything like what we went through. You all matter and you are all important. We hope no one ever has to fight so hard just to get your name back.

For the women — vindicated by a jury of their peers, Rudy Giuliani’s peers, doing their civic duty — winning this substantial recognition of the damage done to them was about getting their name back.

The comments from the women said so much about the damage that Trump and Rudy’s bullying have done to the nation’s civic fiber.

But that’s not what led the coverage of their victory.

Rudy did.

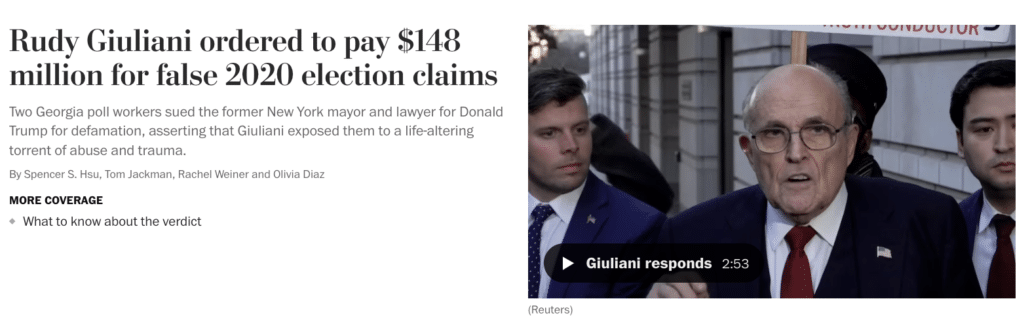

Here’s how WaPo covered it.

WaPo first named Freeman and Moss in ¶3 of the story. The entire story quotes just 23 of their collective words after the verdict (though quotes or describes their testimony at more length, starting 24¶¶ into the story, after repeating Rudy’s false accusations about the women and the debunking presented at trial.

The damages verdict came in a defamation lawsuit filed against Giuliani, 79, by Fulton County, Ga., election workers Ruby Freeman and Wandrea ArShaye “Shaye” Moss, whom Trump and others on the former president’s campaign and legal teams falsely accused of manipulating the absentee ballot count in Atlanta.

“Today is a good day,” Freeman said, standing outside the courthouse with Moss after a jury awarded the mother and daughter pair $75 million in punitive and $73 million in compensatory damages for defamation and emotional distress.

[snip]

Their attorneys in closing arguments had urged jurors to “send a message” to Giuliani and others in public life that the “facts matter.” On Friday Moss added, “Giuliani was not the only one who spread lies about us, and others must be held accountable, too.”

By comparison, WaPo cited 58 words from Rudy’s post-verdict comments, with pushback on his claims that he hadn’t had a chance to present a case, but not on his comment that if the 2020 election weren’t exposed we wouldn’t have a country anymore.

Though the story described the verdict as a “potentially worrying sign for him as he faces criminal charges in Georgia accusing him of related efforts to overturn Biden’s victory there,” it didn’t talk about how some of the evidence Rudy withheld in discovery might have made that plight worse.

Here’s how Politico covered it (placed on the front page behind a 1,250-word story purporting to describe how impeachment will work, without mentioning there’s no evidence of wrongdoing).

Politico got the names of Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss in the subhead and the second paragraph.

Politico sandwiched some of Freeman’s comments, 47 quoted words in ¶19, in-between two paragraphs — starting at ¶9 and in ¶24– quoting 49 words of Rudy’s comments.

A few minutes later, Giuliani stood outside the courthouse and declared, “I don’t regret a damn thing.”

The former mayor and federal prosecutor called the monetary award “absurd” and said he would appeal. He denied responsibility for the threats and harassment that Freeman and Moss received — including a bevy of unambiguously racist, violent messages — and said that he receives “comments like that every day.”

[snip]

“Today’s a good day. A jury stood witness to what Rudy Giuliani did to me and my daughter — and held him accountable,” Freeman told reporters after the verdict was delivered. “We still have work to do. Rudy Giuliani was not the only one who spread lies about us, and others must be held accountable, too,” she said, without elaborating.

[snip]

But after the verdict on Friday, Giuliani offered a different reason for declining to take the stand: “I believe the judge was threatening me with the strong possibility that I’d be held in contempt or that I’d even be put in jail,” he said.

Giuliani didn’t repeat his false claims about Freeman and Moss Friday, but continued to air false claims that the 2020 election was stolen. “My country had a president imposed on it by fraud,” he declared.

Rather than mentioning Moss’ tribute to other civil servants, Politico focused closely on tensions between Rudy and his attorney, Joe Sibley.

Even though the reporters on this story, Kyle Cheney and Josh Gerstein, provide some of the best coverage of all things January 6, the story didn’t mention that by blowing off discovery in this case, Rudy may have tried to keep evidence hidden from Jack Smith.

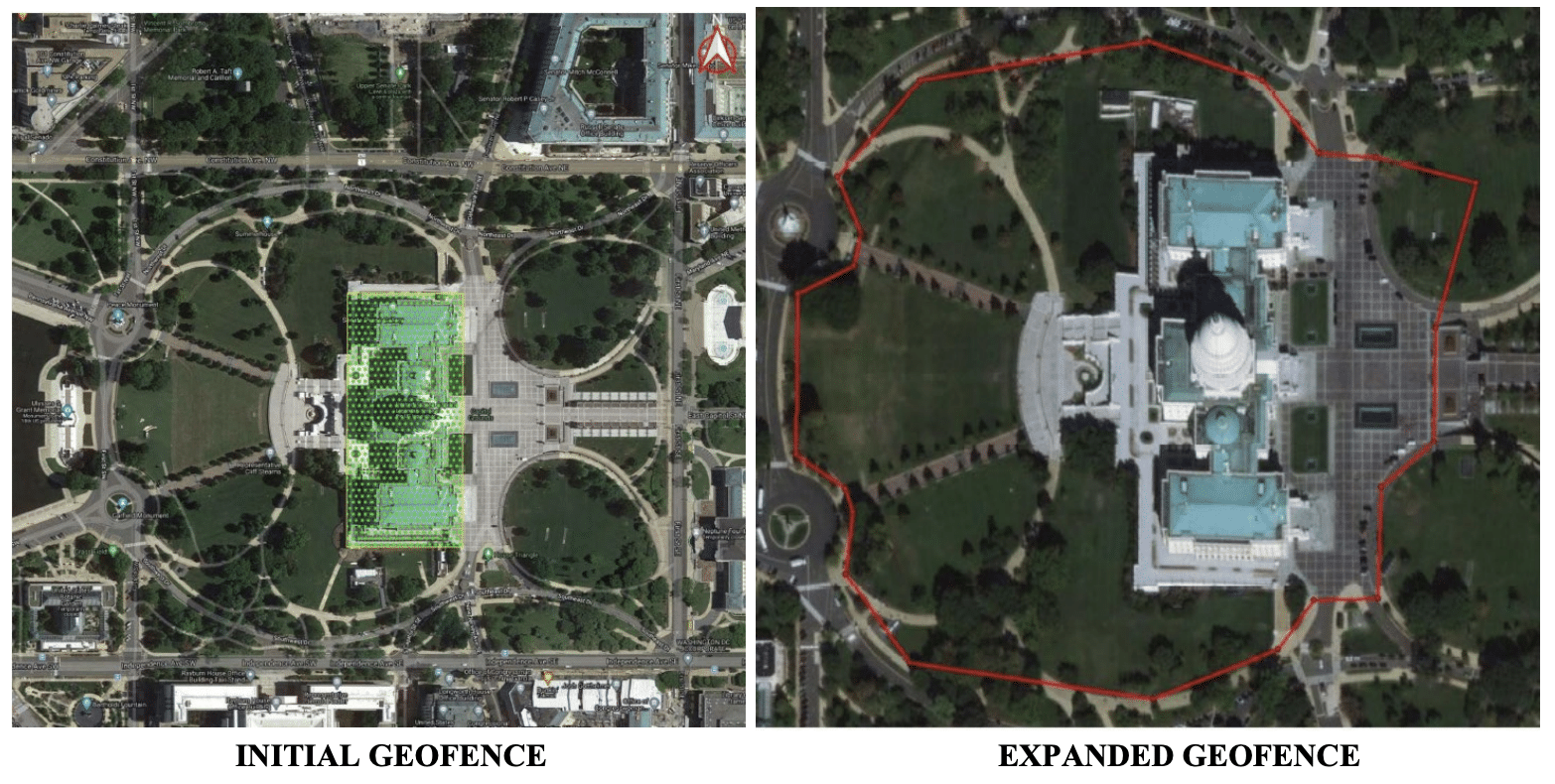

Like the other outlets, NYT’s story led with an image of Rudy.

But it focused paragraphs two through four on the women.

Judge Beryl A. Howell of the Federal District Court in Washington had already ruled that Mr. Giuliani had defamed the two workers, Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss. The jury had been asked to decide only on the amount of the damages.

The jury awarded Ms. Freeman and Ms. Moss a combined $75 million in punitive damages. It also ordered Mr. Giuliani to pay compensatory damages of $16.2 million to Ms. Freeman and $16.9 million to Ms. Moss, as well as $20 million to each of them for emotional suffering.

“Today’s a good day,” Ms. Freeman told reporters after the jury delivered its determination. But she added that no amount of money would give her and her daughter back what they lost in the abuse they suffered after Mr. Giuliani falsely accused them of manipulating the vote count.

Because of that early focus, the dead tree version of today’s paper got Freeman’s name — and her declaration that it was a good day — on page A1 three times.

It closed with Freeman’s promise of more.

“Our greatest wish is that no election worker or voter or school board member or anyone else ever experiences anything like what we went through,” she said.

And while this is a an artificial measure, this NYT story also managed to quote more of Freeman’s speech — 31 words — than Rudy’s — 28. While it quoted Rudy attacking the verdict and standing by his lies, it did not repeat his other lies.

As with all the others, this story didn’t consider whether Rudy was protecting himself criminally by withholding related information in discovery.

I get that these measures are totally artificial. I mean this as observation, not criticism.

I get that Rudy is the famous one, Rudy makes this a tale of downfall. Even bmaz made this about Rudy, not the women who faced him down, Ruby Freeman and Shaye Moss.

But I was really really struck by how, even in their vindication, the heroism of what these women did, the heroism of election workers refusing to be bullied, still wasn’t the focus.