How Does the CIA-on-the-Hudson Program Interact with Secure Communities?

The AP has another installment of their series on the NYPD intelligence department’s mapping of ethnic neighborhoods in New York. As always, you should read the whole thing, as well as the documents showing the spooks’ data collection on innocent Moroccans and Moroccan-Americans.

The AP has another installment of their series on the NYPD intelligence department’s mapping of ethnic neighborhoods in New York. As always, you should read the whole thing, as well as the documents showing the spooks’ data collection on innocent Moroccans and Moroccan-Americans.

One question I came away with, though, was how this program interacted with Department of Homeland Security’s Secure Communities program.

Secure Communities, recall, involves information sharing from local law enforcement to the FBI to DHS.

When state and local law enforcement arrest and book someone into a jail for a violation of a state criminal offense, they generally fingerprint the person. After fingerprints are taken at the jail, the state and local authorities electronically submit the fingerprints to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). This data is then stored in the FBI’s criminal databases. After running the fingerprints against those databases, the FBI sends the state and local authorities a record of the person’s criminal history.

With the Secure Communities program, once the FBI checks the fingerprints, the FBI automatically sends them to DHS, so that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) can determine if that person is also subject to removal (deportation). This change, whereby the fingerprints are sent to DHS in addition to the FBI, fulfills a 2002 Congressional mandate for the FBI to share information with ICE, and is consistent with a 2008 federal law that instructs ICE to identify criminal aliens for removal. Secure Communities does not require any changes in the procedures of local law enforcement agencies or jails.

By that process, DHS identifies people it can deport so as to meet the quota set for them by Congress.

As DDay has written repeatedly, this process has led to the deportation of low-level undocumented people, not the hardened felons the program was designed for. And this, in turn, makes local law enforcement less effective, because it makes immigrant communities less willing to cooperate with the cops because doing so might get them deported.

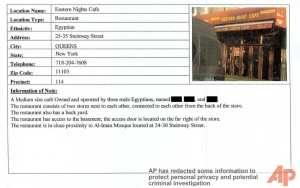

As the documents made available by AP make clear, when the NYPD’s spooks case out businesses, they note whether they are owned by citizens of ethnic (even Italian!) descent, or (as with the Eastern Nights Cafe profile, above) non-citizens. This effectively means NYPD’s spooks are, among other things, creating a database of the statuses of key members of ethnic communities throughout the city. Also, since the NYPD had a set of questions to ask anyone arrested or on parole from the Moroccan community, it also means the normal law enforcement process was being used to collect a database of information on immigration statuses and habits.

The AP story seems to suggest that NYPD keeps this information in a database separate from their other database system.

The information was recorded in NYPD computers, officials said, so that if police ever received a specific tip about a Moroccan terrorist, officers looking for him would have details about the entire community at their fingertips.

[snip]

Current and former officials said the information collected by the Demographics Unit was kept on a computer inside the squad’s offices at the Brooklyn Army Terminal. It was not connected to the department’s central intelligence database, they said.

The first installment of this series reported that the NYPD had shredded some of its documents to keep aspects of the program–including the fact that they were “building dossiers on innocent people, as these latest documents show they were–secret.

Some in the department, including lawyers, have privately expressed concerns about the raking program and how police use the information, current and former officials said. Part of the concern was that it might appear that police were building dossiers on innocent people, officials said. Another concern was that, if a case went to court, the department could be forced to reveal details about the program, putting the entire operation in jeopardy.

That’s why, former officials said, police regularly shredded documents discussing rakers.

But they did pass some of the information to the CIA via back channels.

Intelligence gathered by the NYPD, with CIA officer Sanchez overseeing collection, was often passed to the CIA in informal conversations and through unofficial channels, a former official involved in that process said.

Mind you, that doesn’t mean this information was shared with DHS’ Immigration and Customs Enforcement, leading to deportations.

But given information sharing laws included within the PATRIOT Act, this intelligence might well be legally available to the Federal government (but possibly illegal for them to keep, given that it is potentially illegal domestic intelligence).

All of which leads me to wonder: has the CIA-on-the-Hudson make NYC less safe, because it has turned the local cops into officers combining law enforcement, intelligence, and immigration mapping?