Latif and the Misattribution Problem: “All Arabs Look the Same”

I’m going to have at least two more posts on Adnan Farhan Abd Al Latif (for background see this post), both in response to this post from Mark Denbeaux and Ben Wittes’s response to it.

In this post, I want to demonstrate a possible mistaken assumption many of us have been making as we try to read through the redactions, which is that the only source of potential irregularity in the document at the heart of Latif’s habeas case may have arisen out of translation problems.

Denbeaux describes what he believes the circumstances of the report at the heart of the Latif case to be.

To illuminate how the presumption works, the majority utilizes a hypothetical that does not properly apply to Latif’s case. The hypothetical depicts a government intelligence officer taking the statement of a third party informant. The majority would have us presume that the officer accurately wrote down what the third party informant said, though not presuming the informant’s statement was itself true. This seems to make sense until you apply it to the facts of Latif. A fair and thorough reading of the opinion suggests that the document and information being redacted is a report from an interrogation of Latif that contains opponent-party admissions. The interrogation likely involved an interrogator, a translator, and Latif. Thus, the third party informant in the majority’s hypothetical is Latif himself.

But that’s not exactly what Janice Rogers Brown wrote in the majority opinion in this case. In addition to requiring us to presume that the officer accurately wrote down what the third party informant said, she also wants us to presume that the government officer accurately identified the source.

The confusion stems from the fact that intelligence reports involve two distinct actors-the non-government source and the government official who summarizes ( or transcribes) the source’s statement. The presumption of regularity pertains only to the second: it presumes the government official accurately identified the source and accurately summarized his statement, but it implies nothing about the truth of the underlying non-government source’s statement. [my emphasis]

That’s an important distinction because there are hints that misattribution might be a significant issue in this case as well.

First, the government reply to the Circuit Court tries to refute just that possibility along with mistranslation. “Those similarities – which square with the external evidence about [redacted] make it highly unlikely the report resulted from a mistranslation or misattribution” (PDF 8)

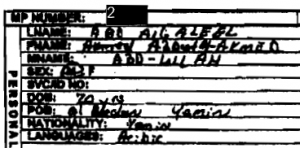

Then, even going back to Latif’s CSRT in 2004–at which the allegations he fought at Kabul, the same allegations at issue here, were presented–he insisted he was not the person referred to in the unclassified summary of charges against him.

I told you I wasn’t the person they were referring to. I never went to the places that you said I did. I am not the person this case is based on.

Also remember that the government is not relying on a discrete, self-contained report on Latif alone. Rather, it has presented just fragments of a larger report, as David Tatel noted in his dissent.

The Report’s heavy redactions–portions of only [redacted] out of [redacted] pages are unredacted–make evaluating its reliability more difficult. The unredacted portions nowhere reveal whether the same person [one and a half lines redacted] or whether someone else performed each of these tasks. And because all the other [redacted] in the Report are redacted, the district court was unable to evaluate the accuracy of [redacted] by inquiring into the accuracy of the Report’s [redacted].

That’s important because several of the intelligence reports reporting on detainees Pakistan turned over to the US in December 2001 are group reports (I’ve determined this by searching on the report name among Gitmo files). TD-314/00684-02, which I suspect is the report in question, includes reports from at least 9 detainees. TD-314/00685-02 (obviously, a closely related report) refers to at least 7 detainees. Another, TD-314/00845-02, catalogs the transfer of at least 8 detainees (a number of whom are also mentioned in TD-314/00684-02) from Pakistani to American custody. And IIR 7 739 3396 02 lists 84 detainees purportedly captured with Ibn Sheikh al-Libi. That is, even if I’m incorrect in my supposition that TD-314/00684-02 is the report in question, chances are quite good that the report deals with multiple detainees in the same report and the redactions Tatel describes serve to hide the other detainee stories told in the same report.

Furthermore, the internal distinctions between detainees in these reports do not appear to be clear cut. Read more →