Imagine if David Addington had co-signed the torture memos written by John Yoo?

I wanted to comment on a Quinta Jurecic column about the Barr Memo that Merrick Garland’s DOJ chose to withhold parts of, as well as this thread from Kel McClanahan responding to Jurecic. Their exchange focuses on how judges may have responded to Donald Trump’s Administration, and what kind of the traditional deference we should expect Garland’s DOJ to get. I’d like to add a few points that may show one possible angle for accountability for Bill Barr moving forward.

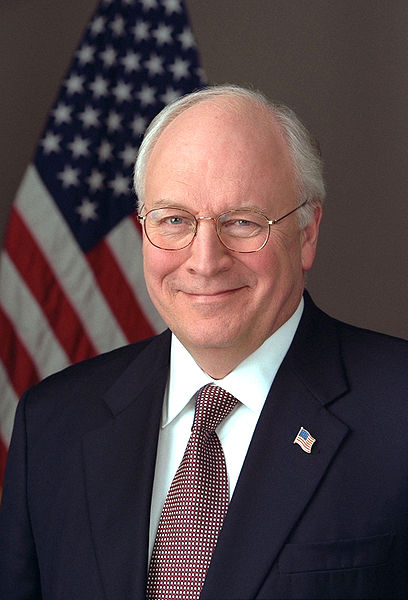

Those points start in the difference between Dick Cheney and Bill Barr. Bill Barr is not Dick Cheney. Both men were the masterminds of horrible policy under their respective (most recent) president. Both, in different ways, badly politicized the government. But Dick Cheney was, in my opinion, the most accomplished master of bureaucracy that DC had seen in a very long time. Barr, by contrast, either didn’t have Cheney’s bureaucratic finesse or just didn’t fucking care to hide his power plays. And the difference may provide means for accountability where it didn’t under Obama.

The worst Bush policies that Cheney implemented were torture and Gitmo, warrantless wiretapping, and the Iraq War. The first two implemented illegal policies by using Office of Legal Counsel to sanction them in advance. And, significantly (but not entirely) because of that, Obama never found the political means to fully excise those earlier policies. Obama only ever got paper prohibitions on torture, he never closed Gitmo, and one of the last things Loretta Lynch did was finalize an effort to legalize the last bits of Stellar Wind by approving EO 12333 sharing rules.

I believe that’s because Cheney used OLC specifically and the Executive bureaucracy generally to make any reversals more costly, a reversal of a position of the Executive Branch, rather than a treatment of crime as crime.

Barr used OLC too, plus he shielded a bunch of epically corrupt efforts to turn DOJ into the instrument of Trump’s personal will under his prerogative as Attorney General, especially prosecutorial discretion. The Barr Memo itself — a request to be advised to make a decision that Trump was not guilty of obstruction and then to announce it — was what he claims to be an instance of prosecutorial discretion. The decision to engage in unprecedented interference with Roger Stone’s sentencing was billed as an incidence of prosecutorial discretion. The decision to reverse the Mike Flynn prosecution, which entailed reversing prosecutorial decisions his own DOJ had approved at the highest levels, adopting a standard on crime that was inconsistent with every precedent, and ultimately included inventing evidence and altering documents, all that was billed as an instance of prosecutorial discretion. The decision to not only protect Rudy Giuliani from legal consequences of participating in an information campaign waged by a known agent of Russia, but also to ingest that disinformation and use it to conduct a criminal investigation of Trump’s rival’s son was also billed as an instance of prosecutorial discretion.

But in all those actions, Barr took steps that necessitated further exercise of corruptly exercised “prosecutorial discretion,” which snowballed. This is why the content of the Barr memo, which we can anticipate with a high degree of certainty, matters. The Barr memo necessarily addresses the pardon dangles (as well as the stuff that Barr said couldn’t be obstruction if a President did it). And I believe that the content of the Barr memo likely contributed to this snowball effect, possibly leading Barr to take later steps to try to limit the impact of having issued a prosecutorial declination for a crime still in progress, which in turn snowballed.

The aftermath of this effect is one detail that Jurecic and McClanahan don’t address. Jurecic says that under Trump,

judges were, perhaps unconsciously, responding to their own distrust in Trump’s oath of office by denying him—in one form or another—the presumption of good faith

She argues that Amy Berman Jackson’s anger about the memo is just another instance of this. That may be true, in part.

But it is also a fact that after ABJ presided over the Stone and Manafort cases, and as such ABJ has a detailed knowledge of what the Mueller Report showed that Barr did not get in the 48 hours while he was trying to get advice on how best to give Trump a clean bill of health (and, indeed, his public comments show he never got that detailed knowledge). In both those cases, Barr abused his discretion as Attorney General to try to make a pardon unnecessary, the snowball effect that his memo may have necessitated.

In service to his effort to minimize Stone’s prison time, Barr treated a threat against ABJ personally as a technicality. Then he lied about what he had done, falsely claiming that he had used the same thought process ABJ had when in fact he instead said threats against her could have no effect on the trial. After he treated the threat against ABJ as a technicality in the Stone case, a Mike Flynn supporter riled up by the lies Barr mobilized to try to overturn Flynn’s prosecution threatened to assassinate Emmet Sullivan. And even after that, Barr kept throwing more and more resources at undoing two decisions Emmet Sullivan made in December 2019, that Flynn’s lies were material and that prosecutors had not engaged in misconduct in his prosecution.

With his memo on the Mueller Report, Barr turned at least the year-plus prosecution of Roger Stone over which ABJ presided — and to a lesser degree the 18-month Paul Manafort prosecution — into legal nullities, in advance.

In short, it may be true that judges generally and ABJ specifically distrusted the good faith of Barr and DOJ’s effort to protect Barr.

But it is also the case that in the wake of this memo, Barr usurped the judicial authority of both ABJ and Emmet Sullivan and he took steps that minimized and contributed to dangerous threats against both.

ABJ is angry. Reggie Walton is angry. Other DC District judges are angry. But they’re angry in the wake of Attorney General Bill Barr usurping their authority and dismissing violent threats against them and their colleagues.

This is one way Barr is different from Cheney. Cheney’s decisions, too, involved treating judges like doormats. In the effort to legalize a part of Stellar Wind in 2004, for example, DOJ told Colleen Kollar-Kotelly that she had no authority to do anything but rubber stamp a massive pen register that might collect the Internet records of millions of Americans. But DOJ did that in secret; it was years before any but a handful of Kollar-Kotelly’s colleagues even knew that, and I’m one of the very few human beings who understands that that happened. Where such claims happened in public, as with detainee fights related to Gitmo, even SCOTUS ultimately defied Cheney’s claims about Article III authority in Boumediene. But unlike Barr, Cheney maintained the illusion of legal order, in which Article III could rein in Article II.

Then there’s how they used OLC.

Jurecic portrays the dispute between ABJ and DOJ as one about their candor about the content of the memo.

For all the rhetorical fireworks, the substantive dispute between the government and Jackson is relatively narrow. It more or less boils down to an argument over whether or not the Justice Department was adequately precise in court about the specific arguments the memo addressed, and whether the department misled the court on the subject.

That’s part of it, but there’s another part that Jurecic and McClanahan don’t address — and that DOJ did not address at all in their response to ABJ, something that goes as much to the core of the deliberative claim as the substance of what Barr was trying to do.

ABJ complained not just that DOJ’s two declarants, Paul Colburn and Vanessa Brinkmann, and the attorney arguing the case, Julie Straus Harris, weren’t sufficiently clear about the substance of the memo (and I’m somewhat sympathetic to those who said she should have figured this out).

ABJ also made several process complaints about the memo — first, that Brinkmann’s declaration did not include details that are required in such declarations:

[Brinkmann] does not claim to have any personal knowledge of why the document was created or what its purpose might be, and while she states generally at the beginning of the declaration that she consulted with “knowledgeable Department personnel,” she does not state that she spoke with any particular person to gain first hand information about the provenance of this document. Id. ¶ 3. Instead, she appears to rely on her review of the document itself to make the following unattributed pronouncements about the decision that is supposedly at issue:

While the March 2019 Memorandum is a “final” document (as opposed to a “draft” document), the memorandum as a whole contains pre-decisional recommendations and advice solicited by the Attorney General and provided by OLC and PADAG O’Callaghan. The material that has been withheld within this memorandum consists of OLC’s and the PADAG’s candid analysis and legal advice to the Attorney General, which was provided to the Attorney General prior to his final decision on the matter. It is therefore pre-decisional. The same material is also deliberative, as it was provided to aid in the Attorney General’s decision-making process as it relates to the findings of the SCO investigation, and specifically as it relates to whether the evidence developed by SCO’s investigation is sufficient to establish that the President committed an obstruction-ofjustice offense. This legal question is one that the Special Counsel’s “Report On The Investigation Into Russian Interference In The 2016 Presidential Election” . . . did not resolve. As such, any determination as to whether the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense was left to the purview of the Attorney General. [emphasis original]

She also complained that Straus Harris included a “flourish” on similar topics that was not based on the declarations before her.

The flourish added in the government’s pleading that did not come from either declaration – “PADAG O’Callaghan had been directly involved in supervising the Special Counsel’s investigation and related prosecutorial decisions; as a result, in that capacity, his candid prosecutorial recommendations to the Attorney General were especially valuable.” Id. at 14 – seems especially unhelpful since there was no prosecutorial decision on the table.

These are complaints about process, how certain content got into the declarations and memos submitted before her court, as much as they are about content. Again, DOJ simply blew off these complaints in their response to ABJ.

ABJ explains why they’re important in the section of her opinion addressing any claim to attorney-client privilege.

There are also other problems with the agency’s showing.

While the memorandum was crafted to be “from” Steven Engel in OLC, whom the declarant has sufficiently explained was acting as a legal advisor to the Department at the time, it also is transmitted “from” Edward O’Callaghan, identified as the Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General. The declarants do not assert that his job description included providing legal advice to the Attorney General or to anyone else; Colborn does not mention him at all, and Brinkmann simply posits, without reference to any source for this information, that the memo “contains OLC’s and the PADAG’s legal analysis and advice solicited by the Attorney General and shared in the course of providing confidential legal advice to the Attorney General.” Brinkmann Decl. ¶ 16.19

The declarations are also silent about the roles played by the others who were equally involved in the creation and revision of the memo that would support the assessment they had already decided would be announced in the letter to Congress. They include the Attorney General’s own Chief of Staff and the Deputy Attorney General himself, see Attachment 1, and there has been no effort made to apply the unique set of requirements that pertain when asserting the attorney-client privilege over communications by government lawyers to them. Therefore, even though Engel was operating in a legal capacity, and Section II of the memorandum includes legal analysis in its assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the purely hypothetical case, the agency has not met its burden to establish that the second portion of the memo is covered by the attorney-client privilege.

19 The government’s memorandum adds that “PADAG O’Callaghan had been directly involved in supervising the Special Counsel’s investigation and related prosecutorial decisions,” Def.’s Mem. at 14, but that does not supply the information needed to enable the Court to differentiate among the many people with law degrees working on the matter.

Effectively, the details inserted into declarations and memos without the proper bases — the flourishes — both hint at and and serve to hide that there is no regularity to either the prosecutorial decision or the OLC advice included in this memo. Had Brinkmann supplied the details that would make her declaration proper — “well, I asked Ed O’Callaghan and he said this wasn’t so much Engel giving Barr advice but instead a bunch of men sitting in Barr’s office laying a paper trail” — it would have given the game away. But that’s what the record describes, and the import of the unexplained structure of this “OLC memo” — which normally would be given great deference in the case of deliberative claims — which is co-authored by someone acting in a prosecutorial role.

And rather than address ABJ’s complaints, the DOJ response admits that OLC is not authorized to make decisions for other parts of DOJ.

One relevant factor in determining whether a document is predecisional is whether the author possesses the legal authority to decide the matter at issue. See, e.g., Electronic Frontier Found. v. DOJ, 739 F.3d 1, 9 (D.C. Cir. 2014) (“OLC is not authorized to make decisions about the FBI’s investigative policy, so the OLC Opinion cannot be an authoritative statement of the agency’s policy.”).

And unstated in this Frankenstein structure is that the memo asks Ed O’Callaghan to make a decision that OLC has said that prosecutorial figures cannot make about the President.

This is why the comparison with Cheney is useful. John Yoo and Steven Bradbury wrote some unbelievably inexcusable memos to authorize the illegal actions Cheney wanted to pursue. They were used as (and indeed, at one point CIA asked for) advance prosecutorial declinations for crimes not yet committed. But with one exception from Bradbury, they maintained the form of an OLC memo. They started their memos with the assumptions that their ultimate audience had asked them to consider, performed the illusion of legal review, and provided the answer they knew their audience wanted.

Imagine if John Yoo had put David Addington or John Rizzo’s names on his memo as co-author; it would change the legal value of the memo entirely. Sure, we know that Yoo was right there in the room as Addington planned the torture program. But he nevertheless performed the illusion of legal advice.

Not so here.

I think McClanahan is right that the declarations being made to hide OLC memos from FOIA release have always been dodgy. I complained about Colburn pulling tricks in 2011 and 2016, for example. But to the extent that anyone looked at those memos — and to the extent that Barack Obama tried to break from the policies justified by them — they nevertheless had the appearance of regularity. They looked like legal advice, even if the legal advice was transparently shitty. And as a result, they made it very hard to hold people accountable for crimes they committed in reliance on the memo.

What separates this memo from the shitty memos used to justify torture is that it doesn’t have the appearance of regularity. It doesn’t even pretend that it’s not excusing (at least insofar as the pardon dangles) crimes in progress.

I agree with McClanahan that DOJ far too often is granted the presumption of regularity. The ultimate fate of this memo may break that habit.

But it also is different, and should be treated differently (and I hope CREW addresses this on appeal) because the process problems with this FOIA — the unexplained claims made by both Brinkmann and Straus Harris — were there to hide the fact that the process that created this memo was irregular, and therefore the claims themselves should not be accorded the presumption of regularity of a deliberative OLC memo.

And once you start to pull the threads on the attempts Barr made to protect Trump, they all tend to suffer from the same inept implementation. That inept — and, I suspect, at times illegal — implementation is what the Garland DOJ on its own or after being forced by the DC Circuit should use to distinguish Barr’s abuse of Attorney General prerogative from that entitled to defense out of an institutional basis. Barr not only abused his power (which Cheney also did) but he did so either without caring enough to pretend he was doing it right, or because he didn’t have the competence to do so (it also probably made things more difficult for him that he had to coerce so many career employees to effect his policies).

Both the torture memos and the Barr memo on the Mueller report were designed (at least in part) to immunize crimes in process. But Cheney’s willing OLC enabler at least insisted on pretending to be an objective lawyer.