I want to talk about DOJ’s career Associate Deputy Attorney General position. I think the way Merrick Garland is using that position to supervise Special Counsel investigations has contributed to the ethical lapses we’re seeing from them.

The current occupant of that role, Bradley Weinsheimer, has garnered attention in recent weeks for his role in some letters exchanged between lawyers for President Biden and DOJ. Between Politico, WaPo, and NYT stories on the letters, they describe the following exchanges:

There’s no report that anyone responded to any of Biden’s 2023 letters. Hur published the letter from Ricard Sauber and Bob Bauer letter in the report, without addressing most of his inappropriate statements. But, after Garland apparently referred the February 7 letter from Ed Siskel and Bauer to Weinsheimer, the ADAG responded to that, while referencing the letter to Hur.

Brad Weinsheimer blows off half Biden’s complaints

After describing that he “serve[s] as [DOJ’s] senior career official,” Weinsheimer proceeded to mischaracterize both the February 5 and the February 7 letters by claiming the complaints were “substantially similar.”

The objections you raise in your letter to the Attorney General are substantially similar to the objections you raised in your February 5, 2024 letter to Special Counsel Hur. In both letters, you contend that the report contains statements that violate long-standing Department policy.

That’s incorrect. They’re not substantially similar. The February 5 letter included the following:

- Bullets one and two (about two pages total) complaining about prejudicial comments

- Three bullets (three through five) about misrepresentations Hur made to substantiate his Afghanistan narrative, none of which Hur addressed in the report

- Bullet six discussing the awareness of Biden’s staffers of his diaries

- Bullet seven that included six other complaints, the last three of which Hur fixed, the first three of which — including the make-believe comment about an attorney-client privileged conversation — he left in

One of those items in bullet seven had to do with Hur’s claim, in the first draft, to have reviewed all the classified information in Reagan’s diaries; he added the word “some” in the final to make it accurate.

The letter to Garland addressed two topics, the second of which was Hur’s use of prejudicial language. Before it addressed Hur’s old geezer comments, though, the letter complained that Hur misrepresented DOJ’s past treatment of presidential and vice presidential diaries, a combination of bullet two, bullet six, and the Reagan diary complaint from the February 5 letter.

Rather than deal with the treatment of diaries, Weinsheimer appears to have just lumped the first part (bullet two in the original) in with the old geezer comments, resulting in Weinsheimer’s mischaracterization of the diaries complaint: Here’s how he described the two complaints.

In particular, you first highlight brief language in the report discussing President Biden’s use of the term “totally irresponsible” to refer to former President Trump’s handling of classified information. Second, you object to the “multiple denigrating statements about President Biden’s memory.”

And based on that mischaracterization, even while claiming to have “carefully considered your arguments,” Weinsheimer issued DOJ’s conclusion that Hur acted within DOJ guidelines.

Having carefully considered your arguments, the Department concludes that the report as submitted to the Attorney General, and its release, are consistent with legal requirements and Department policy. The report will be provided to Congress and released publicly, consistent with Department practice and the Attorney General’s commitment to transparency.

With that characterization, Weinsheimer blew off a number of requested corrections in the letter to Hur — such as the one that Hur invented a hypothetical attorney-client conversation to make the discovery of a box with classified documents in the Wilmington garage more suspicious — and also blew off most of the first half of the letter to Garland, addressing the past treatment of diaries.

The problematic function of the senior Associate Deputy Attorney General

I’m not so much interested in litigating Weinsheimer’s answer: that it was cool for Hur to use prejudicial language, including things like his invented attorney-client conversation. I’m interested in the fact that he claimed to address both the letter to Hur and the letter to Garland and, based on that claim, issued a definitive policy judgment. I’m interested in the function Weinsheimer is playing, because I think it is one thing contributing to the tolerance for ethical lapses among Special Counsels under Merrick Garland.

Politico describes Weinsheimer’s role in making that decision this way:

The next day, Feb. 8, Weinsheimer, the associate deputy attorney general, responded to the letter on behalf of the department. Weinsheimer, a civil servant who has worked at the department for decades, oversees the department’s most politically sensitive matters, including questions on ethics. He has fielded complaints from Hunter Biden’s lawyers about special counsel David Weiss and from Trump’s lawyers about special counsel Jack Smith.

That is, Politico treats Weinsheimer’s role as the traditional role of the career Associate Deputy Attorney General, the guy (if I’m not mistaken, it has always been a guy) one appeals to for ethical review.

That understanding of the role goes back to a guy named David Margolis, who is treated as a saint among DOJers. For 23 years, Margolis served as the guy who’d make the hard decisions — such as what to do with the prosecutors who botched the Ted Stevens prosecution or, worse yet, John Yoo’s permission to torture.

In 1993, he was named associate deputy attorney general. He worked for the deputy attorney general, essentially the chief operating officer of the department. “We would give all the hairballs to [Margolis], all the hardest, most difficult problems, the most politically controversial,” recalled FBI Director James B. Comey, a former deputy attorney general.

Vince Foster’s suicide. Ted Stevens’s botched prosecution for public corruption. The leak of Valerie Plame’s identity. The firings of U.S. attorneys. Margolis was involved — in some way — in them all.

Undoubtedly the most controversial issue he has dealt with came in the early years of the Obama administration. The department’s internal watchdog, the Office of Professional Responsibility, had determined that former Office of Legal Counsel lawyers John Yoo and Jay Bybee had engaged in professional misconduct in writing two memos that gave legal sanction to the use of torture tactics such as waterboarding, as well as wall slamming, extended sleep deprivation and other extreme techniques used by the CIA to interrogate terrorist detainees. Margolis had to decide whether to endorse the OPR’s recommendation that the two lawyers from the Bush administration, who by then had left government, be disciplined.

That was the decision “I agonized over most,” he said. “I knew it would be controversial whichever way it came down.”

In a memo written in January 2010, he conceded that “Yoo’s loyalty to his own ideology and convictions clouded his view” of his professional obligation. But, he concluded, Yoo did not “knowingly” provide inaccurate legal advice and he overturned the OPR recommendation.

That set off a firestorm of criticism from Democratic lawmakers, civil liberties advocates and human rights activists.

“I don’t want to accuse him of bad faith,” said David Luban, a Georgetown University Law Center professor of law and philosophy. “But I will accuse him of bad reasoning.”

But as bmaz wrote on Margolis’ passing, often as not decisions advertised as an ethical decision seemed instead to protect the institution of DOJ.

Sally Yates is spot on when she says Margolis’ “dedication to our [DOJ] mission knew no bounds”. That is not necessarily in a good way though, and Margolis was far from the the “personification of all that is good about the Department of Justice”. Mr. Margolis may have been such internally at the Department, but it is far less than clear he is really all that to the public and citizenry the Department is designed to serve. Indeed there is a pretty long record Mr. Margolis consistently not only frustrated accountability for DOJ malfeasance, but was the hand which guided and ingrained the craven protection of any and all DOJ attorneys for accountability, no matter how deeply they defiled the arc of justice.

After Margolis passed, a guy named Scott Schools played that role for a short period spanning the Obama and Trump years. In such role, in my opinion, he protected the Deputy Attorney General’s office more than DOJ. As one example, Schools was the guy who helped push Andrew McCabe out the door to serve Donald Trump’s whims.

Which is when, in 2018, Jeff Sessions put Weinsheimer, who had played a NatSec role prior to that, in the post.

For the purposes of this post, I’m not really interested in whether Weinsheimer is a good guy or not. There are journalists who are better placed than I am to go chase that down.

I want to talk about how his role on Special Counsels likely ensures an ethical conflict — and all that’s before you consider the extremely likely possibility that he signed off on the McCabe settlement and then was involved in Hur’s selection and supervision, which would be a separate conflict of his own.

Weinsheimer is the supervisor of David Weiss

I don’t dispute Politico’s characterization of how the ADAG position normally works. As laid out in the Margolis bio, the position is supposed to make the difficult decisions and then give such decisions, arguably meant to protect DOJ, the appearance of ethical gravitas. One is supposed to be able to appeal to the ADAG position, in case of ethical problems.

But that depends on the ADAG being outside of potentially unethical decisions in the first place. You can’t review decisions if you were part of them.

At least in the case of David Weiss, Weinsheimer can’t play that role because he is, for all intents and purposes, Weiss’ supervisor — apparently on all matters, not just the Hunter Biden investigation.

In his November testimony to Congress, Weiss described that he has never spoken to his nominal boss, Lisa Monaco, or the person via whom he would normally communicate to his boss, the current Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General, Marshall Miller (as noted below, he described communicating via Miller’s predecessor until 2022, John Carlin).

Q When you have interactions with Justice Department Headquarters or Main Justice, how does that ordinarily happen? Who is your primary point of contact?

A I don’t know that there is an ordinary. I don’t know that I would designate anyone in particular.

Q Under the reporting structure, though, you report up through the Deputy Attorney General. Is that correct?

A That’s correct.

Q And how often do you talk with Ms. Monaco?

A I have never spoken with Ms. Monaco.

Q You’ve never spoken to her?

A Never.

Q Okay. And do you have communications with someone else in the office? Maybe the PADAG?

A I have — my point of contact for the last year, year and a half has been Associate Deputy Attorney General Weinsheimer.

Q Okay. So you’re not in contact on a regular basis with the PADAG, Mr. Miller?

A I am not.

Q Have you ever had communications with him?

A I have not.

Q Okay. So you’ve never had any communications with Marshall Miller or Lisa Monaco?

A I have not.

By his description, he speaks to Weinsheimer regularly, about once a month, and those communications primarily pertain to the President’s son.

Q Okay. And how often do you have communications with Mr. Weinsheimer?

A It varies depending upon what’s going on. But I would say we’ve spoken, before August of 2023, approximately once a month, sometimes more frequently.

Q And was it related to the Hunter Biden case, or was it related to your ordinary duties?

A Generally, it was related to the Hunter Biden case investigation.

That same pace has continued during the period since he had been named Special Counsel.

Chairman Jordan. Have you kept up the rhythm? You said earlier today that you had monthly contacts with the key people at the Justice Department. Have you kept up that same protocol? Has it increased or decreased as Special Counsel?

Mr. Weiss. I guess it’s been, I guess, 3 months. I don’t know that there is much of a practice or that I could say, you know, circumstances. You know, I’ve had several conversations in the last 3 months with Mr. Weinsheimer. I can say that.

Chairman Jordan. So it’s picked up?

Mr. Weiss. It’s — I’ve had probably — yes, several conversations. Whether that will continue or it was unique to the initial stages of the project, I really can’t speak to.

When Weinsheimer reached out to the then-PADAG, Carlin — again, the normal person he would report to — Carlin involved Weinsheimer in all discussions about how to get Special Attorney (not Special Counsel) status to charge the case in a different District with Weiss.

Q Okay. And when did Mr. Weinsheimer first start having communications with you about the Hunter Biden case?

A I think we first spoke about the case in the spring of 2022.

Q And, to the extent you can tell us, what were the nature of those discussions?

A In 2022?

Q Yeah.

A Actually, more accurately, February of 2022, I think, was the first time we spoke. And I would have reached out because we were looking to bring certain portions of our investigation to either D.C. or L.A. At that time, D.C.

Q Okay. Did you call him, or did he call you?

A I reached out by email to the Principal Deputy Attorney General at that time, John Carlin.

Q Okay. So he was the PADAG before Mr. Barr [sic]?

A Correct.

Q And how often had you spoken with Mr. Carlin?

A Before this? Never.

Q Okay. So you initiated email contact with Mr. Carlin, and he referred you to Mr. Weinsheimer?

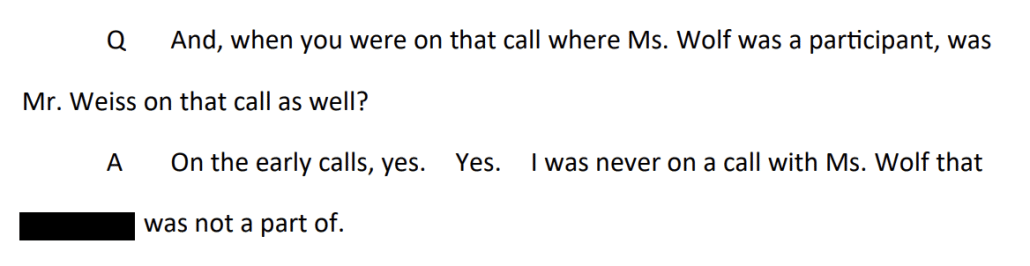

A I initiated email contact with Mr. Carlin, and I subsequently had a conversation with John Carlin, and I believe Brad Weinsheimer was on the call.

Q Okay. And what did they tell you about bringing the case in D.C. or different jurisdictions from yours?

A We discussed the fact that I would — they wanted me to proceed in the way it would typically be done, and that would involve ultimately reaching out to the U.S. Attorney in the District of Columbia. I raised the idea of 515 authority at that time because I had been handling the investigation for some period of time. And, as I said, they suggested let’s go through the typical process and reach out to D.C. and see if D.C. would be interested in joining or otherwise participating in the investigation.

So Weinsheimer was the primary supervisor of David Weiss on the Hunter Biden case.

That makes the meeting with Hunter Biden’s previous attorneys with Weinsheimer — which is fairly routine but was billed as a huge scandal by right wing nutjobs — something else entirely. As Politico described, after months of asking the people who should have had some supervisory role in the investigation, Clark finally emailed Weinsheimer asking whether he could appeal to him.

From the fall of 2022 through the spring of 2023, Clark sought meetings with people at the highest levels of the Justice Department — almost entirely without success. In multiple emails, he asked to meet with the head of the Criminal Division, the head of the Tax Division, the Office of Legal Counsel, the Office of the Solicitor General, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco and the attorney general himself. On Feb. 21, 2023, Clark’s team reached out to multiple officials at Main Justice, who passed his request from one person to the next.

The search ended when Clark sent Associate Deputy Attorney General Bradley Weinsheimer an exasperated email, saying he had asked the government over and over to tell him who at headquarters they could appeal to if Weiss decided to charge their client.

“To date we have heard nothing in this regard,” he added.

“Please advise whether you would be the appropriate person to hear our client’s appeal, in the event that the U.S. Attorney’s Office decides to charge Mr. Biden,” he wrote.

Weinsheimer was indeed the right guy, and he met with Clark and Weiss on April 26.

As Weiss confirmed in his testimony, he attended that meeting with Weinsheimer.

Q Did Mr. Weinsheimer ever tell you that he met with Chris Clark?

A He — if — no. If he met with Chris Clark, I would have been at that meeting.

Q Okay. So there were no one-on-one meetings or telephone calls between Mr. Clark and Brad Weinsheimer?

A I am unaware of any such meeting, and I don’t think any such meeting would have occurred.

Of course Weinsheimer wasn’t going to accede to any of Clark’s requests, or even grant an independent review of some of the shitty things that had already gone on in the case. Presumably unbeknownst to Clark, Weinsheimer was signing off on Weiss’ actions all along.

And he didn’t. Two weeks after they met with Clark, Weinsheimer sent Clark a letter, “referring you back to” Weiss, saying that Weiss had full authority to charge the case wherever he wanted. It’s not clear that Weinsheimer ever revealed that he had assumed a supervisory role on the case a year earlier.

If Weinsheimer played a similar role with Robert Hur, the same would be true. Of course Weinsheimer wouldn’t, in that case, take action after Hur violated DOJ policy by smearing the President. That’s because Weinsheimer would have been in on it, part of the smear.

Except for the Special Counsel appointment

As David Weiss told it, there was an important exception that may have, may still, exacerbate all this.

He did not go through Weinsheimer when requesting Special Counsel authority.

Q And, when you submitted the request, was that through Mr. Weinsheimer?

A No. No, it wasn’t.

Q Did you have communications with Mr. Weinsheimer before you submitted the request?

A I did not have communications with Mr. Weinsheimer about the request before I submitted it.

Q Okay. You just went right to the Attorney General?

A I submitted the request on my own initiative, and, otherwise, I really can’t get into the particulars at all.

Q Right. Have you had subsequent conversations with Mr. Weinsheimer? Is he the individual that you reported to, or —

A After I was appointed?

Q Correct.

A Yes. I continue to discuss the matter with Mr. Weinsheimer.

Q So he’s your primary point of contact still?

A He continues to be my primary point of contact, yes.

And that communication with Merrick Garland was, at least at the time of Weiss’ testimony on November 7 (and so just over a week before Abbe Lowell started asking for discovery and subpoenas on the side channel and the Smirnov FD-1023), the only time he had ever communicated, in any form, with the Attorney General.

Q So the Attorney General has had a couple of silent appearances where this topic has come up, and I guess the question is, did you have direct communications with the Attorney General?

A I’ve never had any direct communications with the Attorney General, save my communication in requesting Special Counsel authority in August of 2023.

Q When you did request Special Counsel authority in August of 2023, how did you request it? Was it in writing or on the telephone?

A It was in writing, and that’s about all I’m going to say about that process.

Q Okay. Did you reach out directly to the Attorney General, or did you go through Mr. Weinsheimer?

A I’m not going to get into anything further. I requested it, and it was granted.

Q Okay.

I started writing this post before the arrest of Alexander Smirnov. At the time, I thought that Weiss might have gone directly to Garland only because Garland had promised the Senate he’d give Weiss Special Counsel authority if ever he asked it. That is, before the Smirnov arrest, it looked only like Weiss collecting on Garland’s promises.

No longer.

The significance of this has been missed. The FD-1023 assessment number, 58A-PG-3250958, cited Executive Branch public corruption. The only way the FD-1023 could be basis for ongoing criminal investigation is if Joe Biden were a subject of the investigation as well. That would make the Special Counsel request not a request for authority to charge in other Districts.

It would arise from the conflict of investigating the President.

Before even interviewing the informant’s handler — to say nothing of Smirnov himself — David Weiss got himself Special Counsel authority.

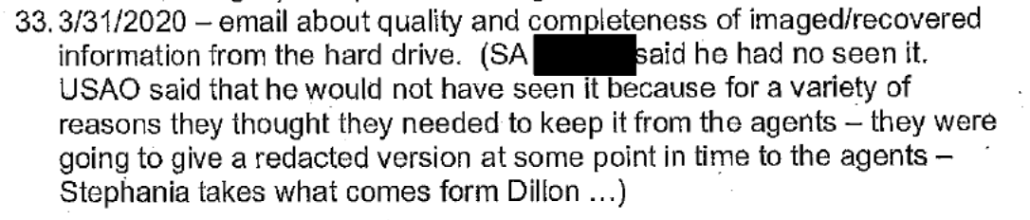

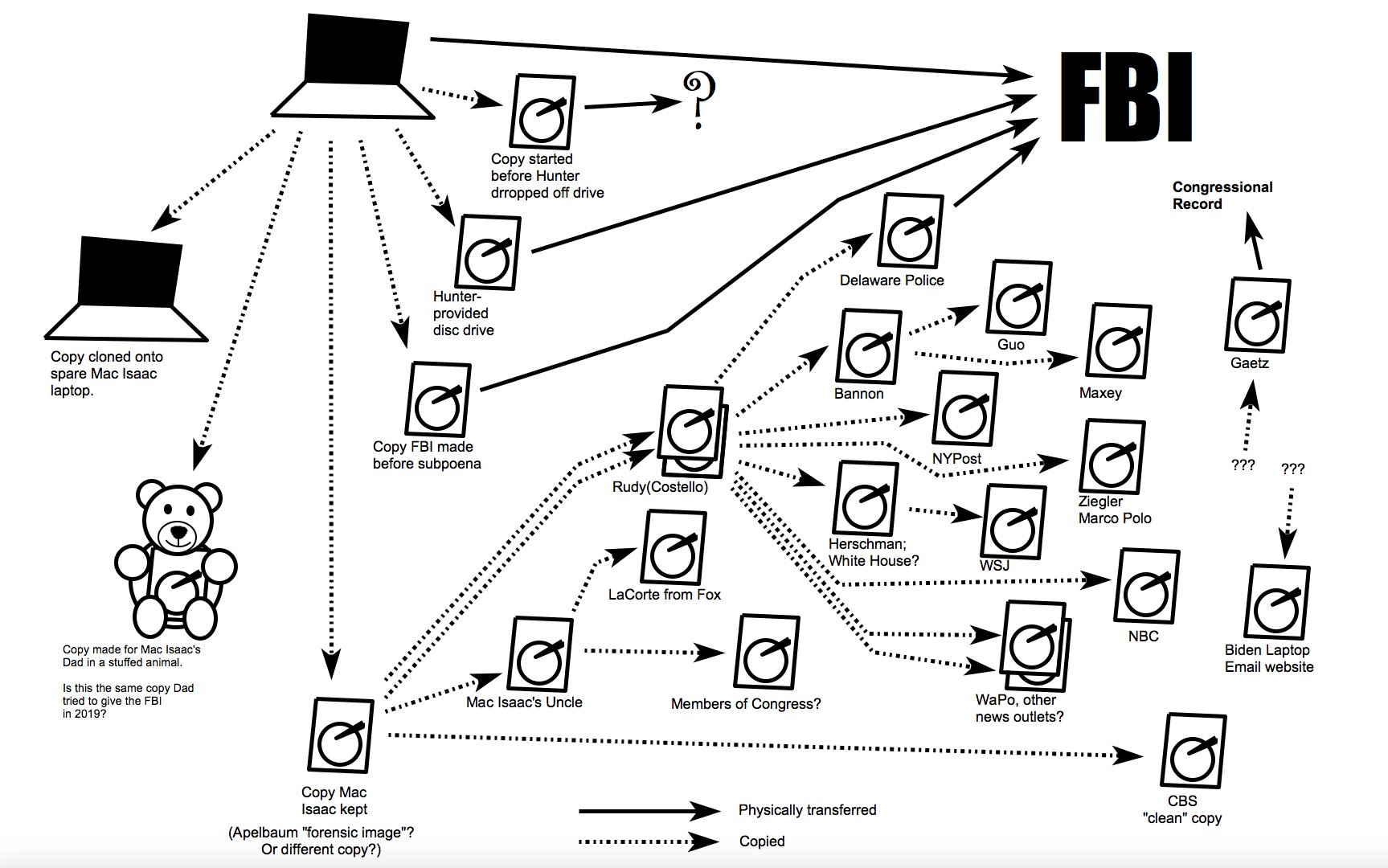

Few agree with me. But I think Weiss has walked himself into a shitshow. Even assuming that none of Abbe Lowell’s bids to throw out the indictments in Delaware and Los Angeles succeed — and the Smirnov indictment would seem to raise still more questions about why Weiss reneged on the plea deal — there’s good reason to believe the motion to suppress evidence from the laptop will surprise a good number of people, including the prosecutors. Consider what it means that attorneys for John Paul Mac Isaac abandoned their argument that the blind computer repairman had legal authority to snoop through and disseminate data he claims to believe belonged to Hunter Biden, focusing seemingly exclusively on a claim that Delaware’s two year statute of limitations for complaint from Hunter has expired: Judge Robert Robinson may not rule on that question, but that legal challenge may have confirmed that JPMI did not own the data he shared with the FBI after the FBI told his father he might not own it. The implications of that are fairly staggering, though I’ll wait before I lay them out explicitly.

And that’s before Smirnov — a 14-year source for the FBI, whose charged report was championed by Attorney General Bill Barr after Scott Brady claimed to have vetted it — starts challenging his own indictment. That’s before either Smirnov or Abbe Lowell raises Weiss’ conflict in charging it. I don’t think David Weiss has the team to pull that prosecution off without major blowback.

If there were a figure like Weinsheimer outside of this investigation to step in, to call a halt to this shitshow, now would be the time to do it. But as I understand it, Weinsheimer can’t do that, because — apparently aside from the Special Counsel request — he has been part of the process every step of the way.

I get why Merrick Garland would have chosen to do it this way: having a career ADAG oversee Special Counsels rather than the PADAG (in which role Hur supervised Mueller). But in SCO investigation after SCO investigation, it has turned the supervisory role into navel-gazing. And the attempt to ensure a higher level of independence has led to grave ethical problems.