Freedom of Association: From Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon to Three Degrees of Terry Stop

One thing the July 24, 2004 Colleen Kollar-Kotelly opinion and the May 23, 2006 phone dragnet application reveal is that the government and the court barely considered the First Amendment Freedom of Association implications of the dragnets.

The Kollar-Kotelly opinion reveals the judge sent a letter asking the government about “First Amendment issues.” (3) Way back on 57, she begins to consider First Amendment issues, but situates the in the querying of data, not the creation of a dragnet showing all relationships in the US.

In this case, the initial acquisition of information is not directed at facilities used by particular individuals of investigative interest, but meta data concerning the communications of such individuals’ [redacted]. Here, the legislative purpose is best effectuated at the querying state, since it will be at a point that an analyst queries the archived data that information concerning particular individuals will first be compiled and reviewed. Accordingly, the Court orders that NSA apply the following modification of its proposed criterion for querying the archived data: [redacted] will qualify as a seed [redacted] only if NSA concludes, based on the factual and practical considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent persons act, there are facts giving rise to a reasonable articulable suspicion that a particularly known [redacted] is associated with [redacted] provided, however, that an [redacted] believed to be used by a U.S. person shall not be regarded as associated with [redacted] solely on the basis of activities that are protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution. For example, an e-mail account used by a U.S. person could not be a seed account if the only information thought to support the belief that the account is associated with [redacted] is that, in sermons or in postings on a web site, the U.S. person espoused jihadist rhetoric that fell short of “advocacy … directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and … likely to incite or produce such action.” Brandnberg v. Ohio

By focusing on queries rather than collection, Kollar-Kotelly completely sidesteps the grave implications for forming databases of all the relationships in the US.

Then, 10 pages later, Kollar-Kotelly examines the First Amendment issues directly. She cites Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press v. AT&T to lay out that in criminal investigations the government can get reporters’ toll records. Predictably, she says that since this application is “in furtherance of the compelling national interest of identifying and tracking [redacted terrorist reference], it makes it an easier case. Then, finally, she cites Paton v. La Prade to distinguish this from an much less intrusive practice, mail covers.

The court in Paton v. La Prade held that a mail cover on a dissident political organization violated the First Amendment because it was authorized under a regulation that was overbroad in its use of the undefined term “national security.” In contrast, this pen register/trap and trace surveillance does not target a political group and is authorized pursuant to statute on the grounds of relevance to an investigation to protect against “international terrorism,” a term defined at 50 U.S.C. § 1801(c). This definition has been upheld against a claim of First Amendment overbreadth. [citations omitted]

Of course, a mail cover is not automated and only affects the targeted party. This practice, by contrast, affects the targeted party (the selector) and anyone three hops out from him. Thus, even if those people are, in fact, a dissident organization (perhaps a conservative mosque), they in effect become criminalized by the association to someone only suspected — using the Terry Stop standard (the same used with stop-and-frisk) — of ties (but not even necessarily organizational ties) to terrorism.

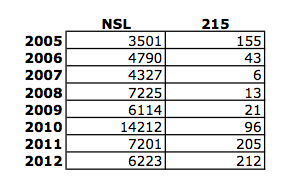

Here’s how it looks in translation, in the 2006 application:

It bears emphasis that, given the types of analysis the NSA will perform, no information about a telephone number will ever be accessed or presented in an intelligible form to any person unless either (i) that telephone number has been in direct contact with a reasonably suspected terrorist-associated number or is linked to such a number through one or two intermediaries. (21)

So: queries require only a Terry Stop standard, and from that, mapping out everyone who is three degrees of association — whose very association with the person should be protected by the First Amendment — is fair game too.

Imagine if Ray Kelly had the authority to conduct an intrusive investigation into every single New Yorker who was three degrees of separation away from someone who had ever been stop-and-frisked. That’s what we’re talking about, only it happens in automated, secret fashion.