Last week, Zoe Tillman noted this FOIA lawsuit from attorney Gene Schaerr, working on behalf of someone who wants to remain anonymous “at present,” suing to obtain records on the unmasking of Trump campaign and transition officials. The thing is, Shaerr isn’t just asking for unmasking records generally.

The odd collection of people being FOIAed

He’s asking for unmasking records pertaining to a really curious group of people:

- Steve Bannon

- Rep. Lou Barletta

- Rep. Marsha Blackburn

- Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi

- Rep. Chris Collins

- Rep. Tom Marino

- Rebekah Mercer

- Steven Mnuchin

- Rep. Devin Nunes

- Reince Priebus

- Anthony Scaramucci

- Peter Thiel

- Donald Trump Jr.

- Eric Trump

- Ivanka Trump

- Jared Kushner

- Rep. Sean Duffy

- Rep. Trey Gowdy

- Rep. Dennis Ross

- Pastor Darrell C. Scott

- Kiron Skinner

Some of these would be obvious, of course: Trump’s spawn, Bannon, Priebus, and Mnuchin. I’m really interested to see Rebekah Mercer (especially given the more we learn on Cambridge Analytica). Mooch is there. The litigious Peter Thiel is there (making him at least a reasonable candidate to be paying for this lawsuit, except for reasons I lay out below).

Mike Flynn, the one person we know to have been unmasked, is not in there (which is particularly odd given all the efforts to find some way to unring Flynn’s guilty plea, though that came after this FOIA was filed).

Then there are the eight members of Congress (in addition to the corrupt FL AG, Pam Bondi, who helped Trump out of a legal pinch in FL after Trump gave her a donation).

Lou Barletta, who’s a loud opponent of “illegal immigration,” a member of the Homeland Security Committee, and who, not long after this FOIA was first filed, prepared a challenge to PA’s Bob Casey in the Senate last year.

Marsha Blackburn, who works on a number of data issues in Congress, and is running to replace Bob Corker as TN Senator. Blackburn worked closely with Tom Marino to shield pharma and pill mills from DEA reach.

Chris Collins from upstate NY. His most interesting committee assignment is on Energy and Commerce, though he has worked on broadband issues.

Tom Marino, former US Attorney for Pennsyltucky who is on the Judiciary Committee. Trump tried to make him the Drug Czar, until it became clear he had pushed through a bill that hurt DEA’s ability to combat the opioid epidemic.

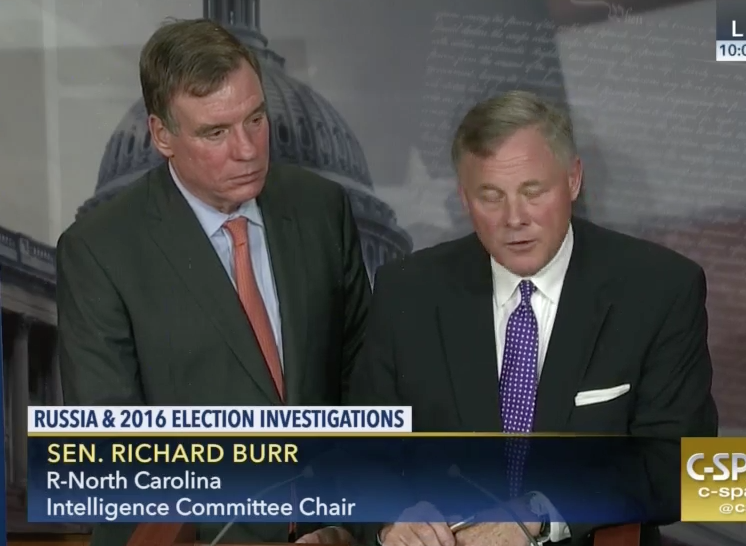

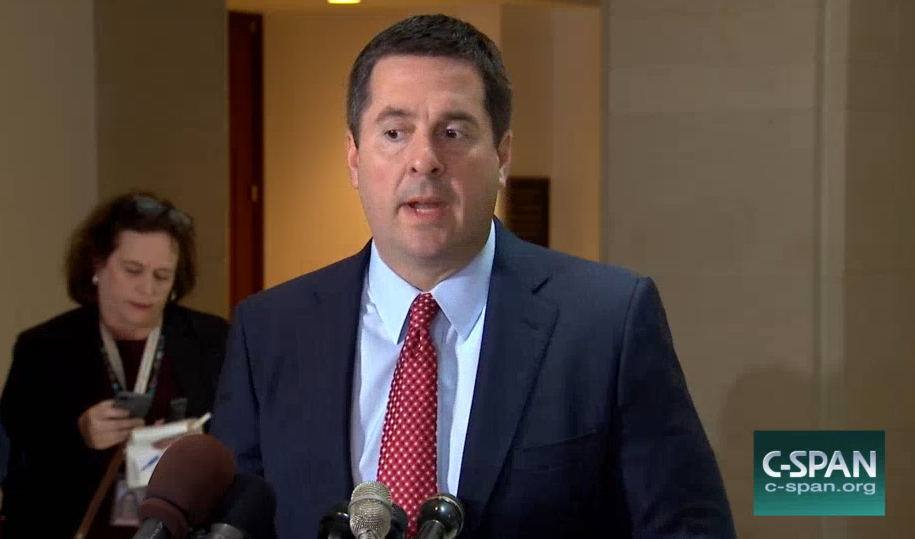

Devin Nunes, whose efforts to undermine the Mueller investigation have been epic, and who first manufactured the unmasking scandal. He’d be a great candidate to be Schaerr’s client, except he would probably just leak this information, which he has already seen.

Sean Duffy, a WI congressman who is chair of the investigations subcommittee of the Financial Services committee, and has been an opponent of CFPB.

Trey Gowdy took over as Chair of the Oversight Committee last year and also serves on the Judiciary and Intelligence Committees. Because of those appointments, even without being designated by Devin Nunes to take the lead on the Mueller pushback, he would have already had the most visibility on the Mueller investigation. But because Nunes put him in charge of actually looking at the intelligence, he is the single Republican who has seen the bulk of the Mueller investigative materials. During Nunes week, he announces his retirement suddenly, and has warned about the seriousness of the Mueller investigation, and he just gave a crazy interview to Fox News (which I’ll return to).

Dennis Ross, from FL, serves on the Financial Services committee.

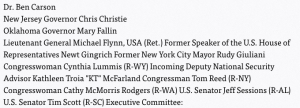

On top of the Republicans, the list includes two of the few African Americans (with David Clarke, Omarosa, and Tim Scott) who supported Trump. Darrell Scott was head of a Michael Cohen invented diversity group hastily put together in April 2016. Kiron Skinner is a legit scholar of Reagan who teaches at Carnegie Mellon and has a bunch of other appointments.

As I said, aside from the big obvious players, this list is a curious collection. Of note, however, four people on it should have a sound understanding of how NSA spying and FISA work: Thiel, Nunes, Gowdy, and Marino. But (again aside from the big players), the international ties of most of these people (Thiel and Skinner are big exceptions) are not readily apparent.

The whack understanding of FISA laid out on the complaint

I’m interested in the FISA knowledge of some people named in this list because of the crazy depiction of FISA that the complaint lays out.

The complaint highlights two departments of NSA, claiming they’re the ones that deal with improper use of intelligence (but does not include the Inspector General).

On information and belief, at least two departments within the NSA handle complaints regarding the improper use of intelligence. These departments are known publicly by the codes “S12,” a code name apparently referring to the agency’s Information Sharing Services authority, and “SV,” a code name apparently referring to the agency’s Oversight and Compliance authority.

As part of the FOIA to NSA, Schaerr asked for anything submitted to these departments.

All reports made to S12 and SV regarding improper dissemination of any individual listed in Question 2, above. See National Security Agency, United States Signals Intelligence Directive 18, § 7.5 (January 25, 2011).

That’s an oddly specific request, unless whoever is behind this request knows there are reports there.

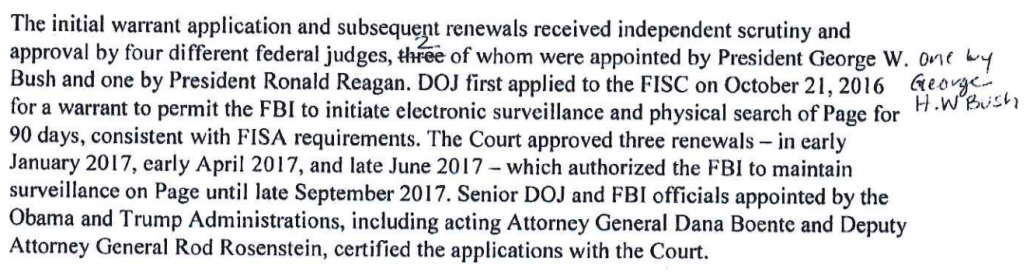

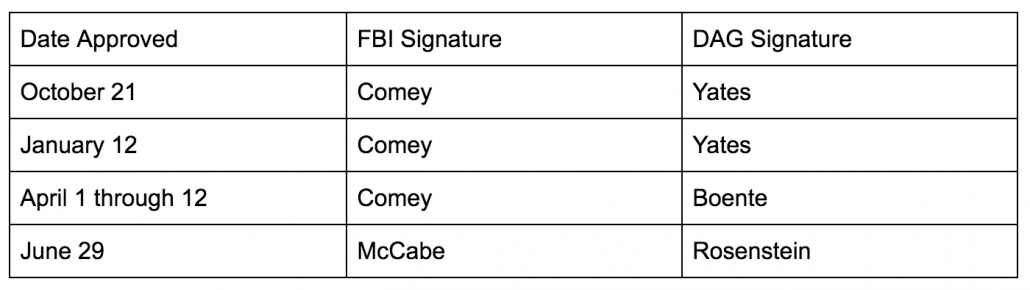

That might suggest Nunes, Gowdy, or Marino is behind the request. But then consider how unbelievably wrong the complaint gets FISA.

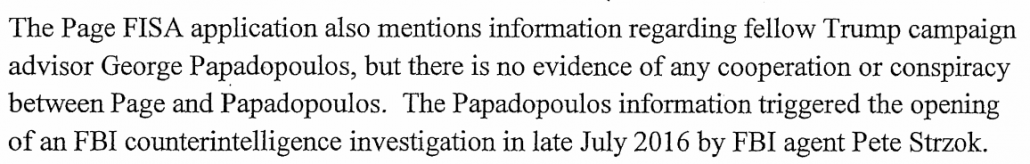

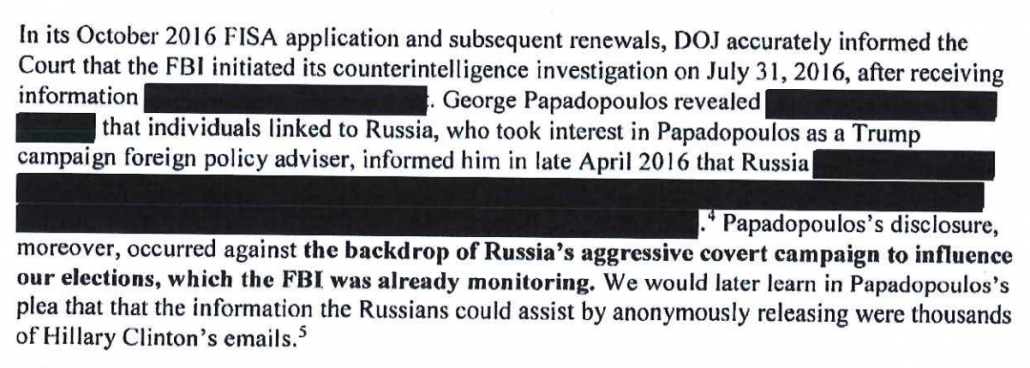

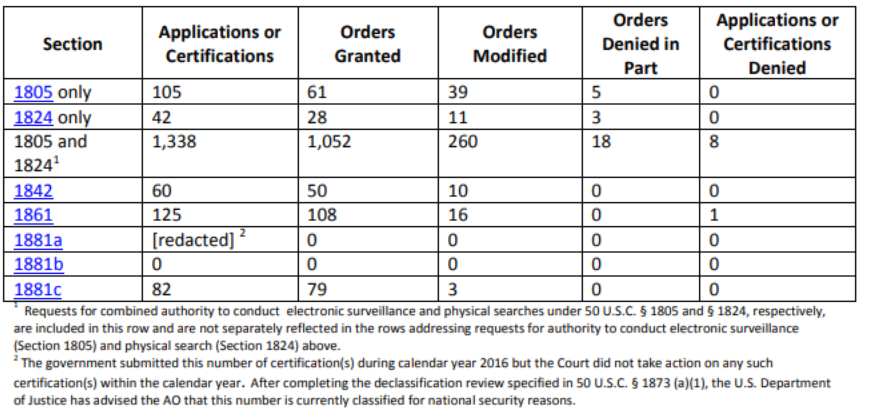

After introducing FISA, it turns exclusively to Section 702, which is odd because the unmasking pseudo-scandal has thus far been based off the unmasking of individual orders.

Plaintiff’s requests in this case concern the Defendants’ use of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA).1 Section 702 of FISA (“Section 702”) empowers the Attorney General and the Director of National Intelligence to jointly authorize “the targeting of persons reasonably believed to be located outside the United States to acquire foreign intelligence information.” 50 U.S.C. § 1881a(a) (emphasis added). Section 702 expressly forbids use of this surveillance process to target persons who are either “United States persons” or located “inside the United States.” Id. at 1881a(b).

The complaint then makes three utterly false statements about how labor is divided between the FBI, NSA, and CIA.

14. The FBI collects data on outgoing communications, i.e., from persons in the United States to persons outside the United States.

15. The NSA collects data on incoming communications, i.e., from persons outside the United States to persons inside the United States.

16. The CIA, like the FBI and NSA, analyzes the information that comes from the FBI’s and NSA’s data collection. Unlike the other agencies, the CIA uses the information to engage in international intelligence operations.

The FBI collects on domestic targets, which can include incoming and outgoing comms, plus anything domestic (such as Sergey Kislyak’s calls across town to Mike Flynn; update — the December 29 calls would have been from DC to Dominican Republic, where Flynn was vacationing). The NSA likewise collects incoming and outgoing comms, as well as stuff that takes place entirely overseas (though very little of the latter is done under 702). Both the other agencies, in addition to CIA, use FISA information to engage in international intelligence operations.

The complaint then claims, in contradiction to a bunch of public information, that minimization equates to completely anonymizing US person data.

Section 702 also requires that foreign intelligence surveillance be conducted consistently with “minimization procedures.” Id. § 1881a(e)(1). These procedures are designed to “minimize the acquisition and retention, and prohibit the dissemination, of nonpublicly available information concerning unconsenting United States persons,” but in a manner still “consistent with the need of the United States to obtain, produce, and disseminate foreign intelligence information.” Id. § 1801(h)(1). As relevant here, minimization procedures must be designed to ensure the anonymity of United States persons who may be incidentally surveilled. Id. § 1801(h)(1), (2).

This comment comes immediately after a paragraph on finished intelligence reports, so this may be an incorrect statement of what masking is.

It then makes a claim about how data gets circulated that entirely ignores the sharing of raw data under 702, and further makes claims relying on this article that aren’t actually supported by the article (admittedly, the article doesn’t describe the sharing of raw data, but its focus in primarily on traditional FISA).

Generally, original raw intelligence is not circulated to other agencies; instead, intelligence reports are created and circulated internally. See, e.g., Gregory Korte, What is ‘unmasking?’ How intelligence agencies treat U.S. citizens, USA Today, (Apr. 4, 2017; 2:14 p.m.), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/ 2017/04/04/ what-unmasking-how-intelligence-agencies-treat-us-citizens/100026368. In the process of summarizing the intelligence, agencies exclude the names of U.S. citizens from the reports, referring to them instead with identifiers like “U.S. Person 1.” Id.

The complaint then describes what sounds like a muddle of upstream collection and back door searches, but gets both wrong.

The NSA also has the ability to search the internet data it collects by entering the name of an individual into a database search tool. This process is known as “upstreaming” and has the effect of creating additional raw intelligence that may contain the names of American persons. Such intelligence is also subject to the usual masking requirements and procedures.

This is wrong because upstream collection uses selectors, not names, whereas back door searches, which can use a name, are done by all three agencies. Such intelligence would not necessarily be masked at FBI if it made it into an investigative report.

The complaint then points to that godawful Circa report that itself muddles the difference between 702 and 704/705b to claim that they were upstream violations during the campaign cycle.

News reports—as well as a declassified Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) opinion—also note that some Americans had their names upstreamed, in violation of internal policies, during the 2016 election cycle, which the opinion described as a “serious Fourth Amendment issue.” See Declassified FISC Court opinion at 19-20, available at http://bit.ly/FISCopApril2017; Circa News, Obama intel agency secretly conducted illegal searches on Americans for years, May 23, 2017), https://www.circa.com/story/2017/05/23/politics/obama-intel-agencysecretly-conducted-illegal-searches-on-americans-for-years.

The violations in question, while serious, actually involve back door searches on upstream collection, and to the extent the searches were done on 704/705b targets, would only have happened were there an individualized FISA order against one of the named people (in fact, NSA’s back door searches on US persons are generally limited to people with individualized orders, those who may be targets of a foreign power, or urgent searches following a terrorist attack or similar situation).

In short, it’s a remarkable garble of how FISA really works. That doesn’t exclude Nunes’ involvement (I would hope both Marino and Gowdy have a better understanding of FISA than this, but don’t guarantee it). But it seems to be an attempt to declassify stuff it knows about, even while it exhibits a remarkable misunderstanding of what it’s talking about.

So why are all these Trump toadies worried about being unmasked

All of which brings me to the puzzle: what the hell is his anonymous client up to? Why is the client concerned about this specific selection of transition officials, but not (say) Mike Flynn?

Update: Laura Rozen notes that this list is the list provided here, except with this chunk taken out, and with some weird alpha order going on.