I’ve already done a few posts on the USA Freedumber bill, AKA HR 3361. This post shows that the Administration has gotten explicit that the chaining process is now about “connected” identifiers and not necessarily “contacts” between them. And this post shows they’ve added another trough of compensation at which intelligence contractors can feed.

But I realize now it really needs a systematic comparison of the bill with USA Freedumb, the previously gutted manager’s amendment. This will be a working thread.

PDF 3 Freedumber: Includes language explicitly envisioning getting call records outside of the limited method rolled out here.

(including an application for the production of call detail records other than in the manner described in subparagraph (C))

We know they always planned to be able to get historical call records via the old means (though new language in section C makes it clear the systematic program can get historical records too), but I wonder if this is also there to get call detail records from smaller telecoms.

Here’s that historical language:

in the case of an application for the production on a daily basis of call detail records created before, on, or after the date of the application relating to an authorized investigation [my emphasis]

See this post for how they changed the chaining language on PDF 5.

PDF6 : They changed the minimization language to be tied to “foreign intelligence” information. I wrote about it in this post at the Guardian.

PDF 7: They’ve gotten rid of language limiting emergency authorities to terrorist investigations as shown:

(A) reasonably determines that an emergency situation requires the production of tangible things to obtain information for an authorized investigation (other than a threat assessment) conducted in accordance with subsection (a)(2) to protect against international terrorism before an order authorizing such production can with due diligence be obtained;

The bill keeps the weak prohibition on using stuff that shouldn’t have been gotten under emergency powers (the AG ensures that such data are not used, but then AG is the one who originally thought it’d be kosher in the first place, making the AG the worst person to police its non-usage). So it turns the emergency powers into a bigger loophole.

PDF 11: I noted that they’ve extended compensation beyond just the telecoms to other advisors (AKA Booz). They’ve also given the Booz figures immunity.

(e)(1) No cause of action shall lie in any court against a person who—

(A) produces tangible things or provides information, facilities, or technical assistance pursuant to an order issued or an emergency production required under this section; or

(B) otherwise provides technical assistance to the Government under this section or to implement the amendments made to this section by the USA FREEDOM Act.

PDF 13: Here’s the new definition for Specific Selection Term. I’ll have a post on this later, but suffice it to say that “such as” is the new “relevant to.”

SPECIFIC SELECTION TERM.—The term ‘specific selection term’ means a discrete term, such as a term specifically identifying a person, entity, account, address, or device, used by the Government to limit the scope of the information or tangible things sought pursuant to the statute authorizing the provision of such information or tangible things to the Government.’

I’m not as bugged by “address” or “device” as some others are–I actually think they’re useful. Still, it’s far too broad.

PDF 15: For some reason, Freedumber gives the IC IG 6 months after the DOJ IG finishes his IG report (which retains the gap where 2010 and 2011 are) before he has to submit his report.

Not later than 180 days after the date on which the Inspector General of the Department of Justice submits the report required under subsection (c)(3), the Inspector General of the Intelligence Community shall submit

These shouldn’t need to be sequential. So I wonder why they did this, if not to delay the required reporting out beyond the beginning of consideration of the sunset.

PDF 18: They can keep on dragnetting up until the moment when the new law goes into effect.

RULE OF CONSTRUCTION.—Nothing in this Act shall be construed to alter or eliminate the authority of the Government to obtain an order under title V of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1861 et seq.) as in effect prior to the effective date described in subsection (a) during the period ending on such effective date.

So they’re stocking up on data. And why not! You never know what fun new data you’ll get under the new system you need a dragnet for?

PDF 19: The NGO community is really excited about this addition.

SEC. 110. RULE OF CONSTRUCTION.

Nothing in this Act shall be construed to authorize the production of the contents (as such term is defined in section 2510(8) of title 18, United States Code) of any electronic communication from an electronic communication service provider (as such term is defined in section 701(b)(4) of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1881(b)(4)) under title V of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 1861 et seq.).

I’m not so excited. First, while this language makes it clear the bill does not affirmatively authorized such production, if FISC has already approved it, they don’t need a bill, they’ve got authorization. In addition, I think there are some Internet entities that aren’t included in the definition of electronic communication service providers.’

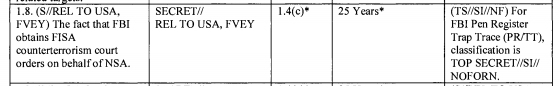

PDF 20: Wow, they’ve utterly gutted the minimization procedures they had tried to add to Pen Register authority (which had included minimization procedures in applications and allowed the judge to review them). Instead of that we get,

(h) The Attorney General shall ensure that appropriate policies and procedures are in place to safeguard nonpublicly available information concerning United States persons that is collected through the use of a pen register or trap and trace device installed under this section. Such policies and procedures shall, to the maximum extent practicable and consistent with the need to protect national security, include protections for the collection, retention, and use of information concerning United States persons.

Which would lead me to believe they either are or intend to resume using this abusively.

PDF 21: THe new bill takes out language trying to cut down on reverse targeting (it had made it illegal if it was a purpose of the acquisition at all). Great. So they’re now legislatively approving reverse targeting.

PDF 21: They changed limits on upstream collection from this:

(B) consistent with such definition, minimize the acquisition, and prohibit the retention and dissemination, of any communication as to which the sender and all intended recipients are determined to be located in the United States and prohibit the use of any discrete, non-target communication that is determined to be to or from a United States person or a person who appears to be located in the United States, except to protect against an immediate threat to human life.’’.

To this (emphasis mine):

(B) consistent with such definition—

(i) minimize the acquisition, and prohibit the retention and dissemination, of any communication as to which the sender and all intended recipients are determined to be located in the United States at the time of acquisition, consistent with the need of the United States to obtain, produce, and disseminate foreign intelligence information; and

(ii) prohibit the use of any discrete communication that is not to, from, or about the target of an acquisition and is to or from an identifiable United States person or a person reasonably believed to be located in the United States, except to protect against an immediate threat to human life.’

The first clause could be read two ways: either to require minimization of data for which recipients were in the US when the data was collected. Or, more likely, they mean to require minimization of data that NSA immediately determines (at the the acquisition) to be in the US. If it’s the latter, it expands upstream collection.

The second clause limits the prohibition on using MCATs (that is, unrelated comms picked up off of targeted comms in the associated inbox) that aren’t targeted to those that involve identifiable US persons. In its discussions with John Bates, the NSA claimed it couldn’t identify which comms were USPs. Which means this would gut the minimization procedures put in place in 2011.

In other words, this language guts John Bates’ efforts to rein in illegal unconstitutional collection of US person content within the US.

PDF 27: As others have noted Freedumber gives the DNI the authority over declassification decisions on significant FISC opinions. It specifies the requirement to apply to any “significant interpretation of the term ‘specific selection term’.”

PDF 33: A reporting requirement on Section 215 is watered down to become a summary of compliance reviews, rather than the reviews themselves.

More troubling still, the same passage eliminates the language requiring reports on PRTT.

(6) any compliance reviews conducted by the Federal Government of electronic surveillance, physical searches, the installation of pen register or trap and trace devices, access to records, or acquisitions conducted under this Act.’’.

PDF 33-34: Freedumber includes a DNI report of aggregate requests, but only with detail on targets, not on number of people affected (or even number of selectors). This is the cover up report for the dragnets. For NSLs, it also only provides the number of requests for information, but doesn’t break out targets. This may be solely because of the subscriber function but it would seem to permit the hiding of bulk collection under other NSLs. (That is, this may well be worse than current reporting.)

PDF 40: Freedumber shifts reporting requirements pertaining to FISC decisions such that Congress only gets notice of a denied or modified application if it includes a significant construction of law. Given that there’s been a huge increase in modified programs, this would serve to hide the kinds of bulk collection going on. It also takes out a requirement that the government summarize what went on.

In addition, there are changes on transparency the companies can do. I’ll sort that out at another time, but even what is there is not transparent.