Update, January 6: After much haranguing from bmaz, I’m updating this post with a new section discussing whether any of the problems with Carter Page’s FISA application would have mattered, had be been criminally charged. I argue that, given precedents about reviewing FISA applications and suppressing warrants, none of the problems with Page’s FISA application would have mattered were it used in a criminal prosecution. As the IG carries out further review of FBI’s FISA work — and as policy makers decide how to integrate the lessons of this IG Report — that reality needs to be part of the consideration, and, in part because Horowitz dodged the issue of these precedents, that’s missing from this discussion.

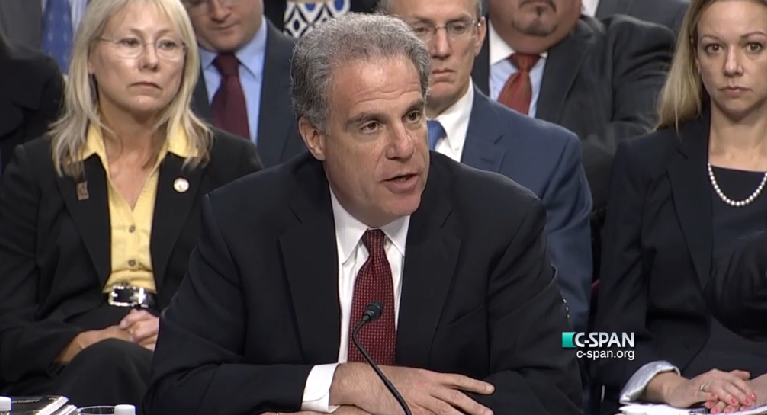

I’ve spent the last week doing a really deep dive into the DOJ IG Report on Carter Page and am finally ready to start explaining what it shows (and what it does not show or where it demonstrably commits the same kinds of errors it accuses the Crossfire Hurricane team of). This post will be a summary of what the IG Report shows about the Carter Page FISA process (with some comment on the FISA process generally).

I will do follow-up posts on — at a minimum — how the report treats “exculpatory” information and the biases of this report, what the report says about Bruce Ohr (where I think this report fails, badly), the details the Report offers on the Steele reports, and what it implies about Oleg Deripaska. I’ll probably do one more demonstrating how this IG Report radically deviates from past history on similar reports in ways that are remarkable and troubling. Eventually I’ll do some posts on what should be done to fix FISA.

This post will address the following topics:

- The predication of the investigation

- The errors impacting Carter Page

- The details about whether Carter Page should have been targeted

- Whether Page would have been able to suppress these warrants had he been charged

The predication of the investigation

The Report is quite clear: “Crossfire Hurricane,” as the investigation was called (henceforth, CH), started in response to the tip Australia provided in the wake of the release of the DNC emails on WikiLeaks.

The FBI opened Crossfire Hurricane in July 2016 following the receipt of ·certain information from a Friendly Foreign Government (FFG). According to the information provided by the FFG, in May 2016, a Trump campaign foreign policy advisor, George Papadopoulos, “suggested” to an FFG official that the Trump campaign had received “some kind of suggestion” from Russia that it could assist with the anonymous release of information that would be damaging to Hillary Clinton (Trump’s opponent in the presidential election) and President Barack Obama. At the time the FBI received the FFG information, the U.S. Intelligence Community (USIC), which includes the FBI, was aware of Russian efforts to interfere with the 2016 U.S. elections, including efforts to infiltrate servers and steal emails belongfng to the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. The FFG shared this information with the State Department on July 26, 2016, after the internet site Wikileaks began releasing emails hacked from computers belonging to the DNC and Clinton’s campaign manager.

The WikiLeaks release made Papadopoulos’ comments to Alexander Downer (and, probably, his aide Erica Thompson, who had an earlier meeting with him in May 2016 before one she attended with Downer) look like the campaign had advance knowledge from the Russians about that release. That it did has since been confirmed with respect to Papadopoulos and — evidence in Roger Stone’s trial suggests — possibly Stone, too.

Australia provided the tip first to the US embassy in London (which may or may not have involved the CIA), which then passed it on to the Philadelphia Field Office, which passed it to the Section Chief of Cyber Counterintelligence Coordination at FBI HQ, where it arrived on July 28. People at HQ, including Peter Strzok, spent the next three days discussing what to do, after which Bill Priestap opened a full investigation to determine whether the Trump campaign was coordinating with the government of Russia.

On July 31, 2016, the FBI opened a full counterintelligence investigation under the code name Crossfire Hurricane “to determine whether individual(s) associated with the Trump campaign are witting of and/or coordinating activities with the Government of Russia.”

A big part of that was trying to figure out how Papadopoulos might have gotten advance notice of the email dump, which is why, over the next 16 days, the FBI opened counterintelligence investigations into the four most likely sources of that information: Papadopoulos himself, Carter Page (who was already the subject of a counterintelligence investigation opened in April 2016), Paul Manafort (who was already the subject of a money laundering investigation opened in January 2016), and Mike Flynn (who had met with Putin the previous December and had ongoing communications with the GRU).

Of the four, Page is the only one not charged with or judged to have lied to obstruct the investigation (though the FBI believed he was not telling the full truth in his March 2017 interviews). The government still has questions about what Page, Manafort, and Papadopoulos did during the campaign period. And a counterintelligence investigation into Flynn remained ongoing as of May. In other words, not only was the investigation justified, but it still is, because questions about everyone originally included remain.

The IG found no bias in the opening of the investigation, and everyone asked said the FBI would have been derelict had they not done so.

That’s worth keeping in mind as Bill Barr lies about the reasons for and results of this investigation, not least because had FBI made different decisions early in the investigation, it might have had more success in figuring out what (especially) Paul Manafort was up to.

The errors impacting Carter Page

In part because the FBI already had substantiated concerns about Page’s willingness to work with known Russian intelligence officers, it moved immediately to get a FISA order on him in August 2016. Lawyers deemed it premature. Then, days after the CH belatedly got the first Christopher Steele reports (which had been churning around FBI for two months), they moved to get a FISA order on him. By the time they applied for the order, they had additional damning information about his July 2016 trip to Russia (that he believed he had been offered an “open checkbook” to form a pro-Russian think tank in the US), but it is true that the dossier was the precipitating event that led the CH team to start the FISA process.

The decision to get a FISA order relying on an unverified tip from an existing “Confidential Human Source” was, per the report, no unusual. Not only does that happen, but Steele is a more credible informant than lots of sources for intelligence targeting. Moreover, by the time of the application, FBI had laid out who his assumed sub-sources were (including Sergei Millian, whom they knew to be interacting closely with Papadopoulos by the time the order was approved).

That said there were clear errors with Page’s applications. Those fall into three areas:

- The FBI did not tell FISC that Page had been an approved contact for CIA until 2013

- The FBI did not describe Steele accurately and failed to update the application as it discovered problems with the dossier

- The FBI did not include information that the IG deemed exculpatory to either Page (correctly) or Papadopoulos (less convincingly)

Notice about Page’s past CIA contacts

Before the FBI first applied for a FISA targeting Page, and again in June 2017, it learned that Page had been approved for “operational contact” from 2008 until 2013. Per a footnote, an operational contact is someone the CIA can talk to about information he has, but not someone they can task to collect information.

According to the other U.S. government agency, “operational contact,” as that term is used in the memorandum about Page, provides “Contact Approval,” which allows the other agency to contact and discuss sensitive information with a U.S. person and to collect information from that person via “passive debriefing,” or debriefing a person of information that is within the knowledge of an individual and has been acquired through the normal course of that individual’s activities. According to the U.S. government agency, a “Contact Approval” does not allow for operational use of a U.S. person or tasking of that person.

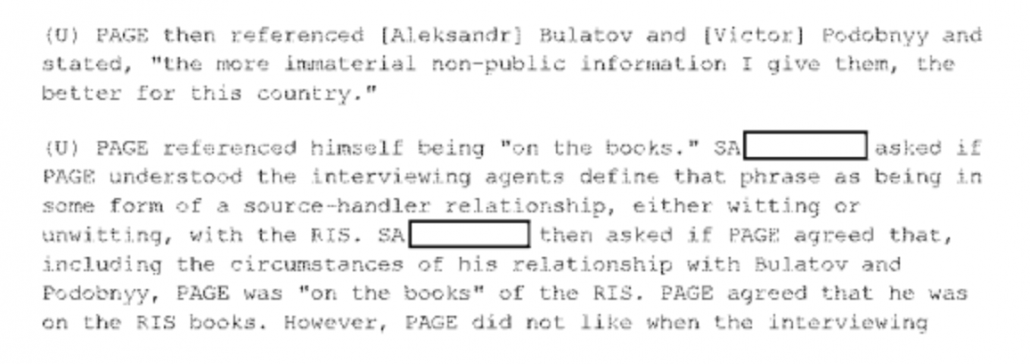

While the details are not entirely clear, Page appears to have told CIA honestly about his contacts with the first Russian intelligence officer who recruited him after he returned to the US from Russia, but not another (probably Victor Podobnyy). His last contact with CIA was in July 2011, which seems to suggest he did not reveal his ongoing ties to Russian intelligence officers to CIA. Moreover, the FBI would come to have concerns about his earlier ties with Russian spies that would not be excused by this CIA designation, not least because after Podobnyy and his fellow Russian intelligence officers were indicted, Page told a Russian stationed at the UN and some others that he knew he was the person described in the indictment, which they discovered when preparing for trial in 2016. The FBI would come to believe Page was less than honest about Page’s comments about showing up in the indictment in 2017.

The FBI did not provide notice of the CIA designation, at all, to FISC. That’s a big problem because the FBI had included both Russian recruitment attempts in its application without explaining that Page had been candid about the first one with the CIA. Worse still, in advance of the last reauthorization in June 2017, FBI lawyer Kevin Clinesmith — who is one of the people who had sent anti-Trump texts using his FBI phone — altered an email to hide the relationship.

None of that changes that Carter Page, throughout this period, told anyone who asked that he thought it was okay to provide non-public information to people he knew to be Russian intelligence officers, nor that he enthusiastically considered taking money from Russia to set up a pro-Russian think tank. But it does raise real questions about whether Page was acting clandestinely, a key requirement for a FISA application.

Inaccurate descriptions of Steele

The IG Report also shows a number of problems with the way the FBI described Steele.

For the first application, that consisted of two problems. First, the FBI didn’t ask Steele’s handler, Mike Gaeta, for his description of Steele’s reliability. As a result, the description overstated how much of his past reporting to the FBI had been corroborated (some of it had been, but much of it was, like the Trump dossier, based on single sources in Russia who couldn’t easily be replicated), and falsely stated that his earlier reporting had been used in court cases, which would have signaled that prosecutors had found it reliable. His reporting had been key to starting the FIFA investigation, but mostly to start the investigation, not to substantiate evidence for trial. Unlike the non-notice about this CIA relationship, this is an error that would have been fixed had the FBI rigorously adhered to the Woods procedures (though the FBI Agent who did the application did have a document — an intelligence report on Steele — he relied on, just not the proper one).

The other initial problem is that the FBI claimed that Steele had not been behind a September 23 Michael Isikoff story relying on Steele’s reporting, something I’ve always found inexcusable. That said, the FBI did alert FISC to the article — they just ridiculously assumed that Glenn Simpson had been the source for the story, not Steele, and did so after initially stating that Steele was behind it. Had they attributed the story to Steele, they would have had to close him as a source weeks before they otherwise did, but it probably wouldn’t have affected the initial approval for the order.

The far more egregious error, however, came on reauthorizations (see this post for a timeline of the events laid out in the report). Starting immediately after they closed Steele as a source, the FBI started getting more details — initially from Bruce Ohr, then Steele’s former colleagues, then his primary sub-source — about his reporting. And most of the things they learned should have raised general concerns about Steele and serious concerns about the reliability of the dossier. Of the ten additional problems DOJ IG found with the applications on the renewals, six of them pertain to providing no notice of increasing reason to doubt the Steele dossier.

I’ll write about the Steele fiasco in a follow-up post. But one detail is worth noting here. There was disagreement between Steele and the FBI about his work dating back to 2013, with Steele understanding he was a contractor and the FBI treating him (partly for bureaucratic reasons) as a CHS. Then, in October 2016, when the CH team tried to task him to answer specific questions about the investigation — about the predicated subjects of the investigation, physical evidence, sub sources who might serve as cooperating witnesses — there was again a misunderstanding about whether Steele was working exclusively for the FBI or simply providing information he was providing to Fusion. As a result, Steele believed he could speak to the press about anything he wasn’t doing for FBI exclusively (which included the dossier), but the FBI considered that cause to stop using him altogether.

Failure to include exculpatory information

Finally, the FBI failed to include exculpatory information pertaining to denials from Page, Papadopoulos, and Joseph Mifsud, and reliability questions about Millian (who was himself the subject of a counterintelligence investigation).

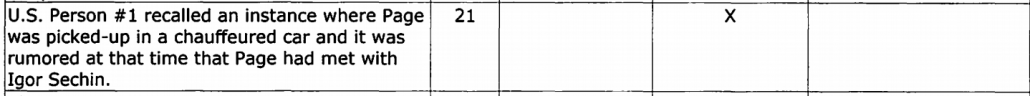

The DOJ IG is absolutely right that FBI should have included Page’s denials in these applications, which include denials that he had ever spoken to Paul Manafort (as alleged in the dossier), had a role in the Republican platform on Ukraine (also alleged in the dossier), or had a role in the email release (the question they were supposed to be answering). All those denials are, as far as we know, absolutely correct. It also excluded his denials of meeting Igor Sechin and Igor Diveykin (as alleged in the dossier), which is probably true, though FBI obtained RUMINT supporting a Sechin meeting.

I’ll address DOJ IG’s stance on the Papadopoulos and Mifsud denials later, both of which were (and were deemed to be by the FBI) at least partly false. But it raises a key problem with a FISA application that — unlike a criminal warrant affidavit — will never be shared with the target of it. Excluding this kind of stuff is generally deemed acceptable in a normal criminal warrant. It is not (and should not be) here, because there will never be discovery. But that raises real questions about what gets counted as exculpatory, which is a topic I’ll return to.

Ultimately, the IG Report judged it should all have been noticed to DOJ which, for the most part, it was not.

Note, Julian Sanchez argues — convincingly, I think — that many of these errors come not from malice or political bias, but from confirmation bias.

Whether Carter Page should have been targeted

The errors in the Page applications are inexcusable.

But they don’t address (and the IG Report pointedly avoids addressing) whether he should have been targeted, from a Fourth Amendment, prudential, or investigative focus standpoint.

Without the full application, it’s impossible to say with certainty whether it would meet probable cause had FBI addressed the problems laid out in the IG Report. But a summary of what the IG Report says appeared in the applications (which I’ve laid out here) suggests there probably was probable cause to support the first two applications. In the first one, the derogatory evidence against Steele’s reporting was not yet known to the agents submitting the application (more on that in a follow-up), so he would have been deemed a credible informant by any measure. And by the second one, the FBI had obtained enough information on Page’s trips to Moscow that likely would have supported a probable cause finding without the dossier — though that finding would have far less to do with whether the Trump campaign had foreknowledge of the email dump, which is unsurprising given that FBI already had an investigation into Page in April 2016. The third and fourth application, however, are much closer calls.

That’s a separate question from whether it was a good idea to get a FISA order on Page, something that multiple people at DOJ raised even before the first application, including Stu Evans (the same guy who ensured there’d be a footnote clarifying that Steele likely was working for a political candidate). As the IG Report describes, everyone at FBI responded by saying they could not pull their punches because of political risk.

According to Evans, he raised on multiple occasions with the FBI, including with Strzok, Lisa Page, and later McCabe, whether seeking FISA authority targeting Carter Page was a good idea, even if the legal standard was met. He explained that he did not see a compelling “upside” to the FISA because Carter Page knew he was under FBI investigation (according to news reports) and was therefore not likely to say anything incriminating over the telephone or in email. On the other hand, Evans saw significant “downside” because the target of the FISA was politically sensitive and the Department would be criticized later if this FISA was ever disclosed publicly. He told the OIG that he thought there was no right or wrong answer to this question, which he characterized as a prudential question of risk vs. reward, but he wanted to make sure he raised the issue for the decision makers to consider. According to Evans, the reactions he received from the FBI to this prudential question were some variations of-we understand your concerns, those are valid points, but if you are telling us it’s legal, we cannot pull any punches just because there could be criticism afterward.

It’s easy to say Evans was right on this. But if you go there, it also raises the question that no Trump supporter ever wants to answer (when discussing this FISA or the use of CHSes): what should FBI have done when faced with evidence that Trump was amenable to the help from Russia and might be coordinating with them?

That’s a debate we really need to have but won’t because Barr is trying mightily to pretend the correct answer is “nothing.”

Which is a pity, because I suspect there are key policy issues that trying to answer the question would raise. For example:

- Aside from the National Security Letters FBI had already served on Page’s providers in the spring, were there other less intrusive kinds of legal process that would have answered some of the questions about Page (and Papadopoulos) without obtaining content?

- Given FBI’s success at gagging providers, why couldn’t it have used normal criminal process?

- Are CHSes really as unintrusive as FBI claims, or should they be reserved for higher predication in the FBI’s Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide (though because CH was a full investigation, they would have achieved that level of predication anyway)

- Why did FBI wait to obtain Page’s financial records — which, for someone working for “free” for the campaign didn’t implicate the campaign at all — until the spring?

- If FBI believed — because this was clearly a counterintelligence investigation — it had to use FISA, did something prevent it from using Section 215 first to obtain more probable cause?

- Was Page even the key person they should have been focusing on?

The last question gets into whether targeting Page with a FISA was the right question — both on the first application, and on the fourth — from an investigative standpoint.

In an effort to ensure the investigation would not leak, from its inception through December 2016, CH was done out of FBI Headquarters (for diagrams of the three different organizations used before Mueller took over, see PDF 117-119), meaning it didn’t have the investigative resources it would have had if it had left the investigations in the field offices. That may have necessitated some resource allocation questions.

Then, by the time of (at least) the second renewal, Page had not only been spun well free of the Trump Administration, but the FBI investigation into everyone but Papadopoulos had already become public.

Because it was not its job, DOJ IG only reported on questions about whether getting a FISA on Page was the right investigative choice — both focusing on him more aggressively than the others, and obtaining a FISA on him.

Start with the former question. By the time CH decided to obtain a FISA order on Page, Papadopoulos had given answers to Stefan Halper that Republicans like to claim were exculpatory but were in fact correctly identified as a cover story and — I think but am awaiting response from the IG’s office — actually could be provably shown to be a lie in real time. Had CH obtained the call records on Papadopoulos at that point rather than a full content warrant on Page, they would have identified Papadopoulos’ ties with Joseph Mifsud, someone already suspected of being a Russian asset. Papadopoulos then laid out the outlines of his interactions with Mifsud in an October conversation with an informant. Had FBI focused on this more closely, they would have known before they interviewed Papadopoulos in January that he had these ties and was lying about them, which might have led FBI to obtain enough information about Mifsud in time to detain him rather than just interview him in early 2017.

The same could be said of Paul Manafort. Had CH focused on him, they might have obtained call records reflecting his ongoing communications with Konstantin Kilimnik, who (as a foreigner overseas) could be targeted under Section 702 and EO 12333. That might have revealed Manafort’s ongoing coordination in real time, which he continues to lie about.

Perhaps they did some of this, or perhaps they could have done it all. But it’s worth asking whether, because the prior concerns about Page meant they could get a FISA on him, they chose that path rather than other less intrusive but potentially more productive approaches.

Then there’s the question of whether ongoing FISAs on Page had merit. The Report suggests the FBI believed the first and, probably, the second order were really productive (the IG only reviewed those comms that were pertinent to its study, but based on that partial review, seemed more skeptical).

But by the later applications, the FBI was not keeping up with the incoming FISA materials, something we’ve seen in FISA collections in the past. There ought to be a rule: if you can’t keep up with incoming surveillance collection, it probably means it’s not important enough to justify the impact on an American.

Although there were no recent relevant FISA collections the team found useful, we were told that the FBI was still reviewing FISA collections identified prior to Renewal Application No. 2.

Finally, by the last collections, the FBI admitted that it was no longer getting anything from the FISA (in part, they believed, because Page knew he was being surveilled).

Case Agent 6 told us, and documents reflect, that despite the ongoing investigation, the team did not expect to renew the Carter Page FISA before Renewal Application No. 2’s authority expired on June 30. Case Agent 6 said that the FISA collection the FBI had received during the second renewal period was not yielding any new information. The OGC Attorney told us that when the FBI was considering whether to seek further FISA authority following Renewal Application No. 2, the FISA was “starting to go dark.” During one of the March 2017 interviews, Page told Case Agent 1 and Case Agent 6 that he believed he was under surveillance and the agents did not believe continued surveillance would provide any relevant information.

There’s an exchange in the Report that leads me to suspect they kept targeting Page not because he remained interesting, but because there were new facilities they had IDed in April 2017 that would be easier to target using FISA than criminal process, including encrypted communications. First, they describe finding out that he used an encrypted app.

NYFO sought compulsory legal process in April 2017 for banking and financial records for Carter Page and his company, Global Energy Capital, as well as information relating to two encrypted online applications, one of which Page utilized on his cell phone.

Then, the report describes “previously unknown locations” they could target, which led them to seek a renewal.

SSA 5 and SSA 2 said that further investigation yielded previously unknown locations that they believed could provide information of investigative value, and they decided to seek another renewal.

There’s very good reason to believe that the FBI either has techniques (probably including hacking phones to get encrypted chat texts) that are easier to conduct using FISA, or techniques they’d like to hide by using FISA.

That’s a policy question that needs to be answered. If FBI is choosing to use FISA to hide techniques, it changes the import and use of the law. But it seems clear: by the time of the fourth if not the third order on Page, they really should have stopped for investigative reasons, but may not have because it’s too easy to avoid the risk of detasking against someone who might be a risk.

Whether Page would have been able to suppress these warrants

Finally, there’s the question of whether, had Carter Page been prosecuted using information obtained under these FISA warrants, he would have gotten any of the information thrown out. As bmaz has been screaming since this IG Report became public, the standard for suppression would require Page to argue that this affidavit didn’t meet the probable cause he was an agent of a foreign power, that the FBI Agents who submitted the application knew or should have known there was a problem with the claims they made in the affidavit, and — because this was a FISA order — he’d have to get a judge to allow him to review the affidavit where no prior defendant has been able to.

And that’s assuming Page even got notice. Often, the FBI will build criminal cases without relying on information obtained under FISA at all. In such cases (as seems to be the case with Lev Parnas and his co-defendants), the government doesn’t have to notice their use of FISA, meaning the defendant never gets the opportunity to try to challenge the FISA warrant. Given how high profile this case is, FBI likely would have tried to avoid giving notice.

Had Page gotten notice, I feel safe in saying he would not have gotten to review his FISA application, because that never has happened, not even in cases with more obviously problematic affidavits.

The IG Report carefully avoids saying whether the applications against Carter Page met the threshold of probable cause, either with or without the errors it lays out. Generally, if a magistrate has found probable cause, defendants have a tough time getting those warrants suppressed; and here, four different District Court judges had approved his applications.

In Page’s case, the way to do this would be to show that stuff in the applications was knowingly false or omitted. In this hypothetical prosecution, Page should have gotten the detail that he was an approved contact with the CIA until 2013, evidence to support his claim that he hadn’t done two of the things in the dossier (interact with Paul Manafort and change the platform), and possibly some of the evidence undermining the Steele dossier (though sometimes the FBI can withhold stuff pertaining to informants).

As for the first, with his efforts to sustain contact with Russia after CIA’s approved contact lapsed and his interactions with a second Russian intelligence officer CIA didn’t know about, it’s not clear that’d be enough to convince a judge that the prior approvals were improper.

As to information proving the dossier wrong, because FBI took such a conservative investigative approach prior to the election, it took some time before the FBI discovered it. The FBI first appears to have gotten evidence that would prove Carter Page wasn’t involved in changing the platform in March 2017, though it appears DOJ’s NSD had better information at the time than FBI. Had FBI taken a more aggressive approach prior to Mueller taking over, they might have developed call records to support Carter Page’s claim that Manafort never returned his emails, but it’s not sure that’s enough. The IG Report doesn’t focus as much on the Manafort exculpatory evidence, perhaps because the FBI plausibly believed Page could have been working with Manafort indirectly, as George Papadopoulos had suggested to Stefan Halper. And, as the IG Report notes but minimizes, one reason the FBI didn’t take details undermining the Steele dossier that seriously is because they believed Steele’s Sub-Informant was withholding information from them, which (given the political firestorm at the time and the claims that the Sub-Source might be in danger are quite likely, even ignoring the possibility the Sub-Source had been involved in disinformation).

Then there’s the standard that would apply to both Fourth Amendment and Franks challenges: whether the FBI affiant on the application knew or should have known their claims were wrong.

In this case, a supervisory special agent who wasn’t closely involved in the investigation was the affiant on the first application. He wouldn’t have known, personally, of any problems with the application. He said he relied on the case agent’s Woods review (though said he routinely does review Woods files). So in that first case, the FBI’s policy of having more senior FBI agents sign FISA applications actually make it harder to challenge the warrant, because it would be harder to claim he knew the application was deficient.

The affiant on the other three applications, called SS2 in the IG Report, was more closely involved in the case. The IG Report provides two specific examples where he swore to something that the IG Report presents as knowably untrue. The first pertains to claims Steele’s Sub-Source made about Millian. But the IG Report said specifically that, “the investigators believed at the time that the Primary Sub-source was holding something back about his/her interaction with [Millian],” which actually accords with what Steele said. Which is to say, the FBI had reason (which may actually have been justified) to believe that the Sub-Source’s comments did not need to be added to the application.

The other thing SS2 might have known by the last application is Page’s past relationship with the CIA; indeed, he made an effort to nail that down for that application. But Kevin Clinesmith’s alteration of the email that thereby hid that Page had been an approved contact for the CIA specifically prevented SS2 from learning that information. So while Clinesmith can (and is in this case) be disciplined, that doesn’t change that the affiant specifically tried to clarify Page’s relationship with the CIA, but got bad information preventing him from being able to.

And it’s not just the two affiants (though they would be the ones at issue in a suppression motion of Franks hearing). The IG Report specifically says that the agents providing that information did not believe they were withholding relevant information.

In most instances, the agents and supervisors told us that they either did not know or recall why the information was not shared with OI, that the failure to do so may have been an oversight, that they did not recognize at the time the relevance of the information to the FISA application, or that they did not believe the missing information to be significant.

The reality is it is usually enough, in criminal prosecutions, for FBI agents to attest to such belief in the case of suppression motions, and probably would be here too, even if Carter Page had succeeded in getting the first ever review of his FISA application.

Finally, there’s the standard for Franks challenges, the means by which, on very rare occasions, defendants argue that the law enforcement officers who obtained a warrant on them were so negligent or malicious in their application so as to merit the warrant and its fruit being thrown out.

Franks challenges require the defendant to prove that false statements in a warrant application are false, were knowing, intentional, or reckless false statements, and were necessary to the finding of probable cause (as this law review article explains at length).

Franks challenges involve heavy burdens for defendants to meet, even at the earliest stages. First, the defendant must make “a substantial preliminary showing that a false statement knowingly and intentionally, or with reckless disregard for the truth, was included by the affiant in the warrant affidavit.”79 A defendant’s claim will fail if it only alleges innocent or negligent misrepresentation;80 it will similarly fail if the court determines that the evidence fails to demonstrate falsity.81 At this stage, the defendant must also show that “the allegedly false statement is necessary to the finding of probable cause.”82 Many Franks challenges fail at this stage because the court determines that the allegedly false statement is not important enough to affect the probable cause analysis.83 If the defendant’s “preliminary showing” clears all three of these hurdles (falsity, intent, and materiality), then the defendant is entitled to a hearing on the allegations.84 At the evidentiary hearing, the defendant has to establish by a preponderance of the evidence the same three things; only then will the evidence be suppressed “to the same extent as if probable cause was lacking on the face of the affidavit.”85 Reviewing courts presume the affidavit’s validity and require the defendant to provide specific allegations and an offer of proof.86

As noted, the IG Report itself notes that the agents believed they had submitted what was necessary for the application, so Page could not show they were knowing falsehoods, meaning he’d have to prove that such a belief was reckless, which — particularly for the matter of relying on Steele — would be hard to do, given that he’s a more credible informant than most FISA informants.

Moreover, aside from Page’s alleged involvement in the platform, it’s not even clear Page could prove that some of the key allegations were false. The FBI did obtain evidence — weak, RUMINT, but nevertheless evidence — that Page may have met with Igor Sechin, and the fact that he met with related people would make disproving those details difficult. Ultimately, the FBI suspected Page was not entirely truthful in his March 2017 interactions with them, and Mueller found that, “Page’s activities in Russia-as described in his emails with the Campaign-were not fully explained.”

Finally, in addition to the Trump-related allegations about Page in his application, the FBI showed that Page willingly remained a recruitment target of known Russian intelligence officers, shared non-public information (possibly deemed trade secrets) with them, and enthusiastically considered an offer of an “open checkbook” to start a pro-Russian think tank. That’s not enough to prove he was an agent under 18 USC 951, but it probably reaches probable cause in any case.

I’m not saying any of this is the way it should be — for FISA warrants or traditional criminal warrants. But that’s the way it is. It is virtually guaranteed that if Carter Page had been prosecuted, he would never have been able to challenge his FISA applications and even if he had, he likely would not have succeeded with either a Franks challenge or a Fourth Amendment suppression motion. That suggests that the way FISA works right now raises the bar well further than it already is for criminal defendants to ensure that the searches against them were proper in the first place.

Update: Corrected post to indicate last contact between Page and CIA was in July 2011.

OTHER POSTS ON THE DOJ IG REPORT

Overview and ancillary posts

DOJ IG Report on Carter Page and Related Issues: Mega Summary Post

The DOJ IG Report on Carter Page: Policy Considerations

Timeline of Key Events in DOJ IG Carter Page Report

Crossfire Hurricane Glossary (by bmaz)

Facts appearing in the Carter Page FISA applications

Nunes Memo v Schiff Memo: Neither Were Entirely Right

Rosemary Collyer Responds to the DOJ IG Report in Fairly Blasé Fashion

Report shortcomings

The Inspector General Report on Carter Page Fails to Meet the Standard It Applies to the FBI

“Fact Witness:” How Rod Rosenstein Got DOJ IG To Land a Plane on Bruce Ohr

Eleven Days after Releasing Their Report, DOJ IG Clarified What Crimes FBI Investigated

Factual revelations in the report

Deza: Oleg Deripaska’s Double Game

The Damning Revelations about George Papadopoulos in a DOJ IG Report Claiming Exculpatory Evidence

A Biased FBI Agent Was Running an Informant on an Oppo-Research Predicated Investigation–into Hillary–in 2016

The Carter Page IG Report Debunks a Key [Impeachment-Related] Conspiracy about Paul Manafort

The Flynn Predication

Sam Clovis Responded to a Question about Russia Interfering in the Election by Raising Voter ID