Update: According to the DOJ IG NSL Report released today, the rise in number of Section 215 orders stems from some Internet companies refusing to provide certain data via NSL; FBI has been using Section 215 instead. However they’re receiving it now, Internet companies, like telephone companies, should not be subject to bulk orders as they are explicitly exempted.

WaPo’s MonkeysCage blog just posted a response I did to a debate between H.L. Pohlman and Gabe Rottman over whether Patrick Leahy’s USA Freedom includes a big “backdoor” way to get call records. The short version: the bill would prevent bulk — but not bulky — call record collection. But it may do nothing to end existing programs, such as the reported collection of Western Union records.

In the interest of showing my work, he’s a far more detailed version of that post.

Leahy’s Freedom still permits phone record collection under the existing authority

Pohlman argues correctly that the bill specifically permits the government to get phone records under the existing authority. So long as it does so in a manner different from the Call Detail Record newly created in the bill, it can continue to do so under the more lenient business records provision.

To wit: the text “carves out” the government’s authority to obtain telephone metadata from its more general authority to obtain “tangible things” under the PATRIOT Act’s so-called business records provision. This matters because only phone records that fit within the specific language of the “carve out” are subject to the above restrictions on the government’s collection authority. Those restrictions apply only “in the case of an application for the production on a daily basis of call detail records created before, on, or after the date of the application relating to an authorized investigation . . . to protect against international terrorism.”

This means that if the government applies for a production order of phone records on a weekly basis, rather than on a “daily basis,” then it is falls outside the restrictions. If the application is for phone records created “before, on, [and] after” (instead of “or after”) the date of the application, ditto. If the investigation is not one of international terrorism, ditto.

However, neither Pohlman nor Rottman mention the one limitation that got added to USA Freedumber in Leahy’s version which should prohibit the kind of bulk access to phone records that currently goes on.

Leahy Freedom prohibits the existing program with limits on electronic service providers

The definition of Specific Selection Term “does not include a term that does not narrowly limit the scope of the tangible things … such as–… a term identifying an electronic communication service provider … when not used as part of a specific identifier … unless the provider is itself a subject of an authorized investigation for which the specific selection term is used as the basis of production.”

In other words, the only way the NSA can demand all of Verizon’s call detail records, as they currently do, is if they’re investigating Verizon. They can certainly require Verizon and every other telecom to turn over calls two degrees away from, say, Julian Assange, as part of a counterintelligence investigation. But that language pertaining to electronic communication service provider would seem to prevent the NSA from getting everything from a particular provider, as they currently do.

So I think Rottman’s largely correct, though not for the reasons he lays out, that Leahy’s Freedom has closed the back door to continuing the comprehensive phone dragnet under current language.

But that doesn’t mean it has closed a bunch of other loopholes Rottman claims have been closed.

FISC has already dismissed PCLOB (CNSS) analysis on prospective collection

For example, Rottman points to language in PCLOB’s report on Section 215 stating that the statutory language of Section 215 doesn’t support prospective collection. I happen to agree with PCLOB’s analysis, and made some of the same observations when the phone dragnet order was first released. More importantly, the Center for National Security Studies made the argument in an April amicus brief to the FISC. But in an opinion released with the most recent phone dragnet order, Judge James Zagel dismissed CNSS’ brief (though, in the manner of shitty FISC opinions, without actually engaging the issue).

In other words, while I absolutely agree with Rottman’s and PCLOB’s and CNSS’ point, FISC has already rejected that argument. Nothing about passage of the Leahy Freedom would change that analysis, as nothing in that part of the statute would change. FISC has already ruled that objections to the prospective use of Section 215 fail.

Minimization procedures may not even protect bulky business collection as well as status quo

Then Rottman mischaracterizes the limits added to specific selection term in the bill, and suggests the government wouldn’t bother with bulky collection because it would be costly.

The USA Freedom Act would require the government to present a phone number, name, account number or other specific search term before getting the records—an important protection that does not exist under current law. If government attorneys were to try to seek records based on a broader search term—say all Fedex tracking numbers on a given day—the government would have to subsequently go through all of the information collected, piece by piece, and destroy any irrelevant data. The costs imposed by this new process would create an incentive to use Section 215 judiciously.

As I pointed out in this post, those aren’t the terms permitted in Leahy Freedom. Rather, it permits the use of “a person, account, address, or personal device, or another specific identifier.” Not a “name” but a “person,” which in contradistinction from the language in the CDR provision — which replaces “person” with “individual” — almost certainly is intended to include “corporate persons” among acceptable SSTs for traditional Section 215 production.

Like Fedex. Or Western Union, which several news outlets have reported turns over its records under Section 215 orders.

FISC already imposes minimization procedures on most of its orders

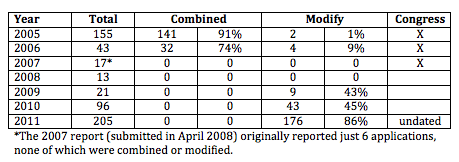

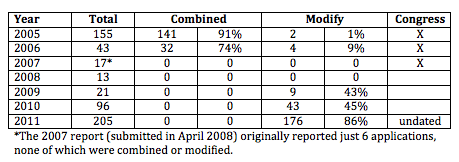

Rottman’s trust that minimization procedures will newly restrain bulky collection is even more misplaced. That’s because, since 2009, FISC has been imposing minimization procedures on Section 215 collection with increasing frequency; the practice grew in tandem with greatly expanded use of Section 215 for uses other than the phone dragnet.

While most of the minimization procedure orders in 2009 were likely known orders fixing the phone dragnet violations, the Attorney General reports covering 2010 and 2011 make it clear in those years FISC modified increasing percentages of orders by imposing minimization requirements and required a report on compliance with them

The FISC modified the proposed orders submitted with forty-three such applications in 2010 (primarily requiring the Government to submit reports describing implementation of applicable minimization procedures).

The FISC modified the proposed orders submitted with 176 such applications in 2011 (requiring the Government to submit reports describing implementation of applicable minimization procedures).

That means the FISC was already requiring minimization procedures for 176 orders in 2011, only 5 of which are known to be phone dragnet orders. Read more →