I regret that I am only now taking a close look at the “transparency” provisions in Patrick Leahy’s version of USA Freedom Act. They are actually designed not to provide “transparency,” but to give a very misleading picture of how much spying is going on. They are also designed to permit the government to continue not knowing how much content it collects domestically under upstream and pen register orders, which is handy, because John Bates told them if they didn’t know it was domestic then collecting domestic isn’t illegal.

In this post, I’ve laid out the section of the bill that mandates reporting from ODNI, with my comments interspersed along with what the “transparency” report Clapper did this year showed.

(b) MANDATORY REPORTING BY DIRECTOR OF NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—Except as provided in subsection (e), the Director of National Intelligence shall annually make publicly available on an Internet Web site a report that identifies, for the preceding 12-month period—

This language basically requires the DNI to post a report on I Con the Record every year. But subsection (e) provides a number of outs.

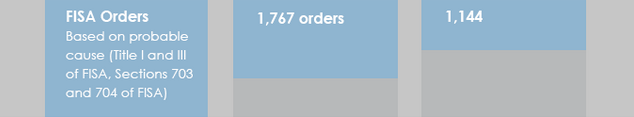

Individual US Person FISA Orders

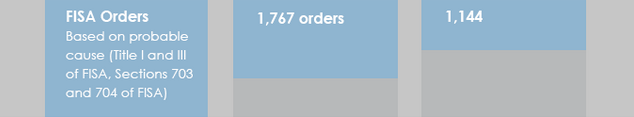

(A) the total number of orders issued pursuant to titles I and III and sections 703 and 704 and a good faith estimate of the number of targets of such orders;

This language requires DNI to describe, in bulk, how many individual US persons are targeted in a given year (there were 1,767 orders and 1,144 estimated targets last year). But it only requires DNI to give a “good faith estimate” of these numbers (and that’s what they’re listed as in ODNI’s report from last year)! If there’s one thing DNI should be able to give a rock-solid number for, it’s individual USP targets. But … apparently that’s not the case.

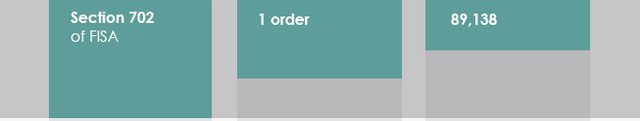

Section 702 Orders

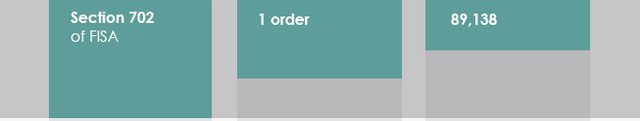

(B) the total number of orders issued pursuant to section 702 and a good faith estimate of—

(i) the number of targets of such orders;

(ii) the number of individuals whose communications were collected pursuant to such orders;

(iii) the number of individuals whose communications were collected pursuant to such orders who are reasonably believed to have been located in the United States at the time of collection;

This language requires DNI to provide an estimate of the number of targets of Section 702 which includes both upstream and PRISM production. Last year, this was one order (ODNI doesn’t tell us, but there were at least 3 certificates –Counterterrorism, Counterproliferation, and Foreign Government) affecting 89,138 targets.

The new reporting requires the government to come up with some estimate of how many communications are collected, as well as how many are located inside the US.

Except DNI is permitted to issue a certification saying that there are operational reasons why he can’t provide that last bit — how many are in the US. Thus, 4 years after refusing to tell John Bates how many Americans’ communications NSA was sucking up in upstream collection, Clapper is now getting the right to continue to refuse to provide that ratified by Congress. And remember — Bates also said that if the government didn’t know it was collecting that content domestically, then it wasn’t really in violation of 50 USC 1809(a). So by ensuring that it doesn’t have to count this, Clapper is ensuring that he can continue to conduct illegal domestic surveillance.

Don’t worry though. The bill includes language that says, even though this provision permits the government to continue conducting illegal domestic collection, “Nothing in this section affects the lawfulness or unlawfulness of any government surveillance activities described herein. ”

Back Door Searches

(iv) the number of search terms that included information concerning a United States person that were used to query any database of the contents of electronic communications or wire communications obtained through the use of an order issued pursuant to section 702; and

(v) the number of search queries initiated by an officer, employee, or agent of the United States whose search terms included information concerning a United States person in any database of noncontents information relating to electronic communications or wire communications that were obtained through the use of an order issued pursuant to section 702;

This language counts back door searches.

But later in the bill, the FBI — which we know does the bulk of these back door searches — is exempted from all of this reporting. As I noted in this post, effectively the Senate is saying it’s no big deal of FBI doesn’t track how many warrantless searches of US person content it does, even of people against whom the FBI has no evidence of wrongdoing.

In addition, note that odd limit to (v). DNI only has to report metadata searches “initiated by an officer, employee, or agent” of the United States. That would seem to exempt any back door metadata searches by foreign governments (it might also exempt contractors, but they should be included as “agents” of the US). Which, given that CIA doesn’t currently count its metadata searches, and given that CIA conducts a bunch of metadata searches on behalf of other entities, leads me to suspect that CIA may be doing metadata searches “initiated” by foreign governments. But that’s a guess. One way or another, though, this clause was written to not count some of these metadata searches. [Update: On reflection, that language may be designed to avoid counting automated processes as searches — if they’re initiated by a robot rather than an employee they’re not counted!]

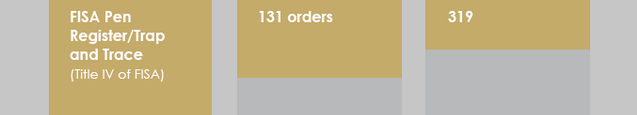

Pen Register Orders

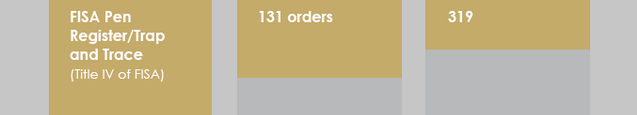

C) the total number of orders issued pursuant to title IV and a good faith estimate of—

(i) the number of targets of such orders;

(ii) the number of individuals whose communications were collected pursuant to such orders; and

(iii) the number of individuals whose communications were collected pursuant to such orders who are reasonably believed to have been located in the United States at the time of collection;

This language counts how many Pen Register orders the government obtains, how many individuals get sucked up, and how many are in the US, both of which are additions on what ODNI reported this year.

But that last bit — counting people in the US — is again a permissible exemption under the bill. Which is, as you’ll recall, the other way NSA has been known to engage in illegal domestic content collection. The only known bulk pen register is currently run by FBI, but in any case, the exemption has the same effect, of permitting the government from ever having to admit that it is breaking the law.

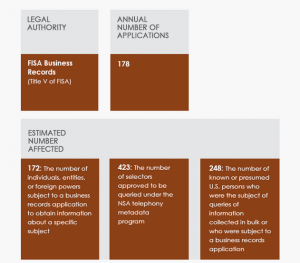

Traditional Section 215 Collection

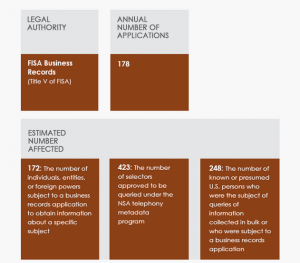

(D) the total number of orders issued pursuant to applications made under section 501(b)(2)(B) and a good faith estimate of—

(i) the number of targets of such orders;

(ii) the number of individuals whose communications were collected pursuant to such orders; and

(iii) the number of individuals whose communications were collected pursuant to such orders who are reasonably believed to have been located in the United States at the time of collection;

This requires DNI to report on traditional Section 215 orders, but the entire requirement is a joke on two counts.

First, note that, for a reporting requirement for a law permitting the government to collect “tangible things,” it only requires individualized reporting for “communications.” “Individuals whose communications were collected” are specifically defined as only involving phone calls and electronic communications.

So this “transparency” bill will not count how many individuals have their financial records, beauty supply purchases, gun purchases, pressure cooker purchases, medical records, money transfers, or other things sucked up, much of which we know to be done under this bill. And this is particularly important, because the law still permits bulk collection of these things. Thus, this “transparency” report creates the illusion that far less collection is done under Section 215 than actually is, it creates the illusion that bulk collection is not going on when it is.

But it gets worse!

Read more →