I noticed earlier yet another hole in USA Freedom Act’s “Transparency” provisions that I’m very intrigued about. It’s part of the definition of “individual whose communications were collected,” off of which all the individualized non-target reporting is based. That definition reads,

(3) INDIVIDUAL WHOSE COMMUNICATIONS WERE COLLECTED.—The term ‘individual whose communications were collected’ means any individual—

(A) who was a party to an electronic communication or a wire communication the contents or noncontents of which was collected; or

(B)

(i) who was a subscriber or customer of an electronic communication service or remote computing service; and

(ii) whose records, as described in subparagraph (A), (B), (D), (E), or (F) of section 2703(c)(2) of title 18, United States Code, were collected.

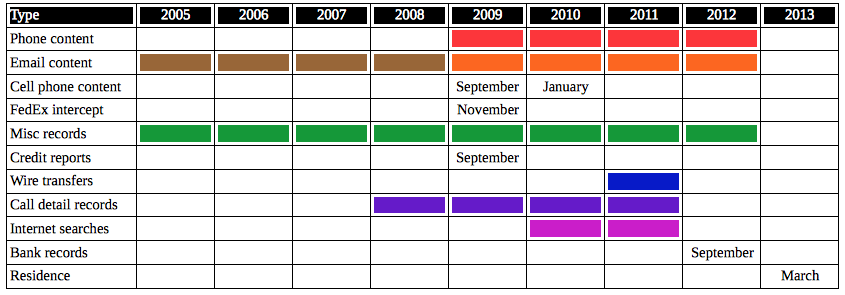

(A), as I’ve explained, clearly exempts all the non-communication tangible things collected under Section 215 — things like bank records and purchase records — from any individualized reporting. That has the effect of hiding at least two known dragnet programs, that collecting international money transfers and that collecting explosives precursors that usually have innocent uses–things like hydrogen peroxide, acetone, and pressure cookers.

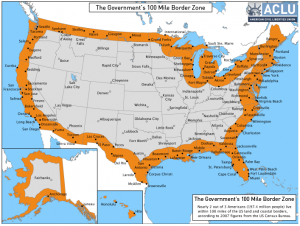

I believe it also exempts location data — as communication from a tracking device — from any reporting, though would be welcome to be proven wrong on that point. If I’m right, though, it will have the effect of hiding likely Stingray and other location tracking programs under PRTT, potentially including the more systematic PRTT program FBI had at least as recently as 2012.

(B), though, is even more fascinating. First, note that (A) does not reflect all electronic communication records collected — only those that involve a “party to a communication” (and no, I don’t understand the boundary there). The underlying definition of communication is very broad, including a bunch of non-communication things, but this “party to” language might limit it. (B), by contrast, is built off a person being a “subscriber or customer” of an electronic communication service or remote computer service, which would include both Internet sites, including search engines, and cloud storage. So I believe this would, if measured in good faith, provide numbers relating to the collection on URL searches and cloud storage uses.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Note what is excluded from the definition being used here, which as far as I know is just pulled outta someone’s arse for this bill (in strikethrough).

(2) A provider of electronic communication service or remote computing service shall disclose to a governmental entity the—

(A) name;

(B) address;

(C) local and long distance telephone connection records, or records of session times and durations;

(D) length of service (including start date) and types of service utilized;

(E) telephone or instrument number or other subscriber number or identity, including any temporarily assigned network address; and

(F) means and source of payment for such service (including any credit card or bank account number), of a subscriber to or customer of such service when the governmental entity uses an administrative subpoena authorized by a Federal or State statute or a Federal or State grand jury or trial subpoena or any means available under paragraph (1).

This language from 2703(c)(2) describes what the government can obtain from stored communication providers without a court order; but note that 2703(c)(1) permits the government to obtain other information (though not content of communications) with a court order based on a relevance standard.

As I read it [insert standard caveats about not being a lawyer, invitations for lawyers to correct me here], if all the government obtains from a cloud or web provider is what are deemed call records or session times (or those other things permissible with a court oder under 2703(1), then it doesn’t count as a communication provided. If they ask for other stuff — identifying information — then it’s a communication. But if they only ask for the communications stuff, then it’s not a communication. And, if I’m reading this correctly (though I’m less sure of this), obtaining someone’s non-communication content stored in the cloud does not amount to collecting communications on them under the larger definition.

Given how crazy this formula is, I’m going to assume this pulled-outta-arse definition is designed to hide some fairly substantive dragnet.

I confess, I have no idea what this is designed to hide. But here are three non-exclusive possibilities.

The Exotic Section 215 Requests

First, consider that the stored communication definition used here is not a definition used for FISA. The closest definition to that is in 18 USC 2709, which is the NSL equivalent for what they’re using here, which is a Title III administrative subpoena. The NSL permits the government to obtain fewer things:

name

address

local and long distance toll billing records

length of service

In fact, that NSL definition is behind the bulk of Section 215 orders. After DOJ published an OLC memo limiting what FBI could get under that NSL definition, more than one Internet company started refusing NSLs for a certain kind of request in 2009, which led FBI to obtain that information under Section 215. Now such orders are now the majority of Section 215 orders.

I had been assuming these searches were for the URL searches of individuals, based on James Cole’s confirmation they can use Section 215 to get URL searches. And they may well be. But that shouldn’t generate a large number people affected (except insofar as someone searched on US businesses, which count as US persons). There’d be no reason to hide that (especially since it will show up as foreign, not domestic, collection under FBI’s exemption). Besides, a person’s URL search might count as a party to a communication.

Perhaps, though, these exotic requests are either collected in bulk (perhaps searches for a certain thing) or they are for some other kind of use.

PRISM Non-Communication

We usually talk about PRISM — Section 702 collection from US-based Internet providers — in terms of communications collected: emails and instant messages.

But we know that, even in the first year of Protect America Act, the government had broadened its requests to include 9 things. Even 6 years ago, those requests seem to include cloud storage, information searches, and Yahoo’s internal records on customers.

The definition of “communications collected from” would seem to exempt not only non-communication data stored in the cloud from its counts, but even communication data.

As with the exotic Internet requests, I’m not sure how these requests would drive up the numbers of people affected. But if they do, by structuring the request in this way, they’d artificially lower the number of people affected by PRISM.

Phone connection chaining

We know the other two kinds of collection — the exotic Internet 215 requests and cloud collection under PRISM — occur. We don’t know what “connection chaining” means in the context of the phone dragnet.

As I have noted, the new Section 215 Call Detail Record function meant to replace the phone dragnet doesn’t actually chain on calls and texts made. It chains on “connections.” Nobody knows what the fuck that means, though in spite of promises ODNI would explain it in their letter supporting the bill, they did not do so. And ODNI has denied my FOIA requests for related language.

It’s SEKRIT. Which means it must be interesting.

That said, I have speculated that it might include finding burner phones (which is fairly uncontroversial, and FBI does it under Hemisphere anyway), using location to map connections (again, that’s something available under Hemisphere), or things like address books and calendars and even personal pictures.

And of course, most of those things would be accessible with smart phones because cloud content is available. Precisely the kind of cloud content dodged by this definition.

Now, I’m still not sure this works. After all, as a Verizon subscriber, if I get connection chained because I’m in someone else’s Verizon address book, it would seem they would have to count me. Or maybe not, because the actual request (all done at the telecom, of course!) wouldn’t be triggered to me, it’d be triggered to my friend.

But it seems at least possible that this definition would hide a great number of potential connections made via cloud information, whether obtained under PRISM or under Section 215’s CDR connection chaining.