Why I Don’t Support USA Freedom Act

Earlier today, Harry Reid filed for cloture for the USA Freedom Act. So Patrick Leahy’s reform for the phone dragnet will get a vote in the lame duck.

As you may remember, I don’t support USAF. Here’s a summary of why.

No one will say how the key phone record provision of the bill will work

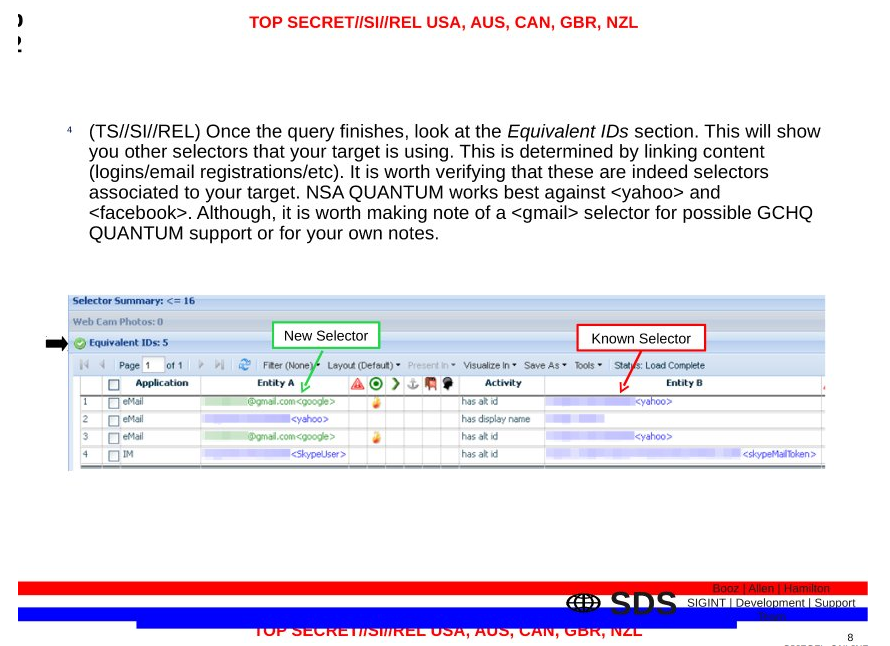

USAF rolls out a new Call Detail Record provision providing for prospective daily collection of selected phone records. While it would replace the phone dragnet — which is a really really important improvement– there are many questions about the provision that James Clapper’s office refused to answer (and refused to respond to a FOIA I filed to find out). Most importantly, no one can explain what “connection chaining” — which clearly permits the chaining on things other than phone calls and texts made — includes. I worry that language will be used to connect on things available through phone cloud storage, like address books, calendars, and photos (which we know the NSA uses overseas). I also strongly believe (though some people I’ve talked to disagree) that Verizon’s supercookie qualifies as a CDR under the bill (it can be collected under other authorities in any case) and therefore will make it easier to access communications records for “correlated” identities accessed via the same phone. Whether this is the intent or not, we know from the Yahoo precedent that there will be significant mission creep within months of passing this bill.

USAF negotiates from a weak position and likely moots potentially significant court gains

Right now, the main PATRIOT authorities at question here — Section 215 and PRTT — are scheduled to sunset in June. They’ll be renewed one way or another. But in April to May, reformers will have more leverage than they do now.

Bill supporters claim civil liberties groups have never gotten concessions from a sunset. That’s plainly wrong, because reformers did on FISA Amendments Act, where (among other things) protection for Americans overseas was won with the wait. Admittedly, given the new Senate, we’d be worse positioned (with the exception of Thad Cochran being potentially better than Barb Mikulski at Appropriations). That said, we would likely be better prepared not to squander our far stronger position in the House, as civil liberties groups did on USAF, so legislatively it might be a wash, though with reformers having more leverage.

More importantly, passing this now may moot court decisions in 3 circuit courts (the 2nd and DC, where phone dragnet challenges have already been heard, and the 9th, where the hearing hasn’t been held yet). While Larry Klayman clearly botched his hearing in DC with a surprisingly receptive panel and a precedent that would make this program glaringly illegal, the 2nd seems otherwise poised to rule the FISC’s redefinition of “relevant to” to mean “everything” illegal, across all programs. In other words, this legislation will probably pre-empt making real change in the courts in the near term. And no one will get standing again on these issues in the near future.

USAF’s effects in limiting bulk collection are overstated

As I said, I believe USAF eliminates the existing phone dragnet by requiring the use of selectors for collection. That’s good!

However, because the bill permits non-communications companies to be used as selectors, it almost certainly won’t end known financial dragnets involving Western Union transfers and purchase records (and as I describe below, those dragnets are also excluded from transparency provisions). I also think the bill will do nothing to limit FBI’s PRTT program (if it still exists — it existed and was sharing data with the NSA at least until 2012); I suspect — this is a wildarseguess — that is a bulky, not bulk, use of Stingrays to get location, which also would be exempted from reporting. There’s absolutely no reason to believe that the bill would affect other PRTT or NSL programs, because the ones included are all currently bulky, not bulk, programs. So it will eliminate the ability for the government to get every phone record in the US, but it will leave other non-phone dragnets intact and largely hidden by deceptive “transparency” provisions.

USAF would eliminate any pushback from providers

USAF provides providers — and 2nd level contractors — expansive immunity. So long as they are ordered to do something, whether they believe it is legal or not, they cannot be held liable. In addition, the bill compensates providers, which the existing Section 215 cannot do (the government even had to stop compensating telecoms after the first 2 dragnet orders). Finally, the bill requires assistance of providers, whereas the existing law can only collect existing business records (I believe the absence of all three things explains the big gaps in the government’s cell phone coverage). These three provisions are designed, I strongly suspect, to overcome Verizon’s disinterest in being an affirmative spy wing of the government, which is probably the real point of this bill. Possibly, they’re designed to get Verizon — the most important mobile provider — to do the kind of affirmative analysis for the government that AT&T currently does.

USAF may have the effect of weakening existing minimization procedures

In at least 3 areas, I worry that USAF will actually weaken existing minimization procedures. Under both the PRTT and Section 215 authority, the FISC currently imposes minimization procedures. For the former, the bill would put the authority to devise “privacy procedures” in the hands of the Attorney General (though says it doesn’t change the law; thing is, FISC minimization procedures aren’t in the law). The bill mandates minimization procedures for bulky collection, but it’s not clear whether those procedures are even as good as what the FISC currently imposes (they’re probably very similar). Most troubling of all, the bill doesn’t provide the FISC authority to require the government to destroy records collected under the emergency provision if found to have been improperly collected, a significant deterioration from the status quo, and one that it appears the FISC may have already needed to use.

USAF’s transparency provisions are bullshit

I don’t mean to be an asshole on this point, but I actually think many of USAF’s “transparency” provisions are counter-productive, because they are very obviously designed to hide the programs that we know exist, but that won’t be affected by USAF’s selection term provisions, because only communications dragnets get counted, sort of; financial dragnets won’t get counted and location dragnets won’t get counted. That will make it very very difficult to organize to eliminate any of the residual bulk programs (because the bill champions will have assured people they don’t exist and they won’t show up in transparency provisions). In addition, they tacitly permit the NSA and FBI to pretend they’re not conducting fairly bulky domestic wiretapping by providing them ways to avoid counting that illegal wiretapping. In addition, the FBI will be permitted to hide how much spying they’re doing on Americans (though for some, not all, provisions, their collection will be reported misleadingly as foreign collection). And the introduction of ranges will hide still more of they spying. See this post for my estimate of how the bill hides millions of Americans affected.

Other laudable provisions — like the Advocate — will easily be undercut

My other big warning about the bill is not meant to disqualify it, but is meant to suggest supporters are vastly overestimating its impact. James Clapper has made it very clear that he intends to ensure the Advocate (or amicus, as Clapper calls it) remains powerless. And the Yahoo documents make it clear that precedent at the FISCR says the ex parte procedures in FISA will be used to prevent the Advocate from reviewing materials she needs to do her job. As I said here, though, that’s not reason to oppose the bill; if PCLOB is any indication, the bill will start us down a 9-year process at the end of which we might have a functioning advocate. But it’s reason to be honest about how leaving ex parte provisions intact in FISA will make this Advocate very weak.

All this is before the things the bill doesn’t even claim to address: back door searches, EO 12333, spying on foreigners.

The bill will get phone records out of the hands of the government. But from that point on, I’m not sure how much of an improvement it is.