Bob Litt: No Contingency Plans for Section 215

A month into the new Congress, neither USA Freedom Act nor a replacement has been reintroduced. Which has led to a discussion of what will happen if Section 215 sunsets in June.

I hope to do my own piece on all of what happens if Section 215 sunsets in the June. But in the meantime, I want to point to three things Bob Litt said in his speech on the topic yesterday. In his prepared speech, Litt defended the program and then re-endorsed USA Freedom with the caveats of his letter to Patrick Leahy on it. First, note a few details here.

Finally, the President directed specific steps to address concerns about the bulk collection of telephone metadata pursuant to FISA Court order under Section 215 of the USA PATRIOT Act. You’ll recall that this was the program set up to fix a gap identified in the wake of 9/11, to provide a tool that can identify potential domestic confederates of foreign terrorists. I won’t explain in detail this program and the extensive controls it operates under, because by now most of you are familiar with it, but there is a wealth of information about it available at IContheRecord.

Litt doubles down on the claim the phone dragnet closes a “gap” that never existed. And he suggests this is solely about “identifying potential domestic confederates” of foreigners. Not only does that obscure that it also serves to identify networks here in the US (as it did after the Marathon bombing, and with Najibullah Zazi) but that two court filings admit that it is also about identifying potential informants on networks of interest, not finding confederates. It also helps NSA to identify which conversations to prioritize for translation or other analysis (meaning it necessarily ties directly to content).

Which is why I find it interesting that Litt follows that disingenuous description of the use of the phone dragnet.

Some have claimed that this program is illegal or unconstitutional, though the vast majority of judges who have considered it to date have determined that it is lawful. People have also claimed that the program is useless because they say it’s never stopped a terrorist plot. While we have provided examples where the program has proved valuable, I don’t happen to think that the number of plots foiled is the only metric to assess it; it’s more like an insurance policy, which provides valuable protection even though you may never have to file a claim. And because the program involves only metadata about communications and is subject to strict limitations and controls, the privacy concerns that it raises, while not non-existent, are far less substantial than if we were collecting the full content of those communications.

Twenty months after Snowden first revealed the phone dragnet, the IC is not admitting what or how this is used (and is maintaining the charade that there aren’t legal problems with having proclaimed everything relevant to terrorism in secret).

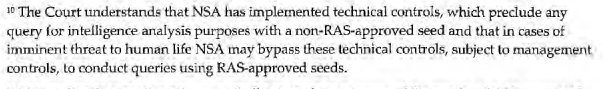

Even so, the President recognized the public concerns about this program and ordered that several steps be taken immediately to limit it. In particular, except in emergency situations NSA must now obtain the FISA court’s advance agreement that there is a reasonable articulable suspicion that a number being used to query the database is associated with specific foreign terrorist organizations. And the results that an analyst actually gets back from a query are now limited to numbers in direct contact with the query number and numbers in contact with those numbers – what we call “two hops” instead of three, as it used to be.

Fact check: The current language of the dragnet orders permits chaining on “connections,” not “contacts.”

Longer term, the President directed us to find a way to preserve the essential capabilities of this program without having the government hold the metadata in bulk. In furtherance of this direction, we worked extensively with Congress, on a bipartisan basis, and with privacy and civil liberties groups, on the USA FREEDOM Act. This was not a perfect bill. It went further than some proponents of national security would wish, and it did not go as far as some advocacy groups would wish. But it was the product of a series of compromises, and if enacted it would have accomplished the President’s goal: it would have prohibited bulk collection under Section 215 and several other authorities, while authorizing a new mechanism that – based on telecommunications providers’ current practice in retaining telephone metadata – would have preserved the essential capabilities of the existing program. Having invested a great deal of time in those negotiations, I was personally disappointed that the Senate failed by two votes to advance this bill, and with Section 215 sunsetting on June 1 of this year, I hope that the Congress acts expeditiously to pass the USA FREEDOM Act or another bill that accomplishes the President’s goal.

As a reminder, when Bob Litt says, “bulk collection,” he is not using common English usage. He is instead referring to the collection of stuff with no discriminators. So the aspiration to collect “all” phone records is bulk under his definition, but the aspiration to collect all US-to-foreign money transfers is not because the latter uses a discriminator (US-to-foreign).

Also note that Litt claims this is based on “telecommunications providers’ current practices,” which is when (during the speech) I started tweeting requests for a divorce lawyer to subpoena some 20-month old Verizon records. Last summer, Verizon said in sworn testimony they only kept records 12 to 18 months, though during the debate Dianne Feinstein revealed they and another carrier had agreed “voluntarily” to keep their phone records 2 years. So has Verizon already extended how long it keeps these records? Or is Bob Litt fibbing here? (My bet is they haven’t because my bet is that “voluntary” retention would have been worked into the new compensation mechanisms of USA Freedom Act.)

After that endorsement for USAF or another bill to pass before the Section 215 sunset, Litt got two more questions on the topic (in addition to one on the FISC advocate, to which he responded he’d like the weak tea advocate of his interpretation of the bill).

In the first question, Cameron Kerry asked what happens if Section 215 sunsets. Litt responded (my transcription):

Good question. The President said he wants to have a mechanism that preserves the essential capabilities of the bulk collection program that we have now without the bulk collection. There’s a proposal up there that would accomplish that. I’m hopeful that we will get that passed. If it sunsets, if it goes away, obviously the program will end. We’ll also lose other authorities that are under the same section, which have nothing to do with bulk collection whatsoever. So at this point we’re still far enough away that I think that we’re not doing extensive contingency planning other than trying to map out the legislative way to get something passed that will accomplish the President’s goals.

One thing to emphasize here — which no one I saw noted — is Litt focuses on the “essential capabilities” of the existing program. That’s not just phone records for contact chaining, as I pointed out above. It includes connection chaining, which I strongly suspect is part of the problem with current compliance.

That is, it would not be enough to just get phone records, because that likely doesn’t give all the parameters for “connections” that are currently in place.

Furthermore, as Litt points out but others have not, if Section 215 sunsets, the IC loses the current authorization they’re using for the phone dragnet, but also the authorizations for what are probably several other bulky programs (the aforementioned money transfer one, one targeted at hotel rooms which might be imperiled anyway because of a pending SCOTUS case, and one or ones targeted at the purchase records of explosive precursors like fertilizer, acetone, hydrogen peroxide, and possibly pressure cookers). In addition, the FBI would lose the ability to get certain Internet records that providers have been able to refuse NSLs for; these currently make up the majority of Section 215 orders (given that I Con the Record said the IC had had 161 phone dragnet targets last year and there were around 180 Section 215 orders, there may well have been more of these Internet requests last year than phone dragnet targets).

Even if there are alternatives for the phone dragnet (I see problems with meeting the government’s goals, rather than just getting phone records, using either PRTT or NSLs), alternatives would be more difficult for the others, including the Internet one (for reasons I don’t understand). That is, a sunset of Section 215 comes with additional costs for the government that not passing USAF (which would close existing gaps) doesn’t.

Not long after this exchange, another questioner asked, “Does this mean government won’t take advantage of ways to extend phone dragnet,” apparently referring to this Charlie Savage report suggesting the government could just continue because the underlying investigations are.

Litt responded by saying there’d be problems to continue to do the dragnet “under this authority.”

I don’t think we’ve thought a lot about contingency plans. I think that if, there’s obviously, I don’t think I’m revealing any deep secrets here. There’s obviously a somewhat more substantial political hurdle in saying, Yes Congress, we know you didn’t reauthorize this but we’re going to go ahead and do it anyway under this authority. We’ll just — I’m hopeful we’ll never have to confront those issues.

While that definitely suggests Litt would advise against continuing the dragnet under Section 215, he was very specific about using Section 215 here, as opposed to some other authority.

Which brings me back to my take. I do believe the government could get some subset of phone records using PRTT or NSLs. But there is a reason why the Administration has resisted calls — specifically saying there are non-technical (suggesting legal) problems with doing so. At the very least, they’re holding out to get the immunity and compensation and provider assistance Congress would be trading for a few small reforms.

But I think they need that package — immunity, compensation, and provider assistance — to do what they want to be done. And they’re not going to get it under PRTT or NSL.