NSA Tried to Roll Out Its Automated Query Program Between Debates about Killing It

As I noted earlier, after reporting in November that there was a debate in 2009 about ending the phone dragnet…

To address their concerns, the former senior official and other NSA dissenters in 2009 came up with a plan that tracks closely with the Obama proposal that the Senate failed to pass on Tuesday. The officials wanted the NSA to stop collecting the records, and instead fashion a system for the agency to quickly send queries to the telephone companies as needed, letting the companies store the records as they are required to do under telecommunications rules.

In a departure from the bill that failed Tuesday, however, they wanted to require the companies to provide the metadata in a standardized manner, to allow speedy processing and analysis in cases of an imminent terror plot. The lack of such a provision was among the reasons many Republicans and former intelligence officials said they opposed the 2014 legislation.

By the end of 2009, Justice Department lawyers had concluded there was no way short of a change in law to make the program work while keeping the records in the hands of the companies, the former officials said.

The AP reported today that there was also a debate about ending the dragnet in 2013 (and if I’m not mistaken, the story has been updated to note that these were two separate debates)….

The proposal to halt phone records collection that was circulating in 2013 was separate from a 2009 examination of the program by NSA, sparked by objections from a senior NSA official, reported in November by The Associated Press. In that case, a senior NSA code breaker learned about the program and concluded it was wrong for the agency to collect and store American records. The NSA enlisted the Justice Department in an examination of whether the search function could be preserved with the records stores by the phone companies.

That would not work without a change in the law, the review concluded. Alexander, who retired in March 2014, opted to continue the program as is.

But the internal debate continued, current and former officials say, and critics within the NSA pressed their case against the program. To them, the program had become an expensive insurance policy with an increasing number of loopholes, given the lack of mobile data. They also knew it would be deeply controversial if made public.

By 2013, some NSA officials were ready to stop the bulk collection even though they knew they would lose the ability to search a database of U.S. calling records. As always, the FBI still would be able to obtain the phone records of suspects through a court order.

Between these two debates (indeed, between the time the NSA shut down the PATRIOT-authorized Internet dragnet and the second debate), on November 8, 2012, the NSA got FISC to approve an automated query.

In 2012, the FISA court approved a new and automated method of performing queries, one that is associated with a new infrastructure implemented by the NSA to process its calling records.68 The essence of this new process is that, instead of waiting for individual analysts to perform manual queries of particular selection terms that have been RAS approved, the NSA’s database periodically performs queries on all RAS-approved seed terms, up to three hops away from the approved seeds. The database places the results of these queries together in a repository called the “corporate store.”

The ultimate result of the automated query process is a repository, the corporate store, containing the records of all telephone calls that are within three “hops” of every currently approved selection term.69 Authorized analysts looking to conduct intelligence analysis may then use the records in the corporate store, instead of searching the full repository of records.70

The January 3, 2014 dragnet order revealed that over the year-plus since FISC authorized this automated query, NSA still had not gotten it working.

The Court understands that to date NSA has not implemented, and for the duration of this authorization will not as a technical matter be in a position to implement, the automated query process authorized by prior orders of this Court for analytical purposes. Accordingly, this amendment to the Primary Order authorizes the use of this automated query process for development and testing purposes only. No query results from such testing shall be made available for analytic purposes. Use of this automated query process for analytical purposes requires further order of this Court.

On March 27, 2014, Obama said he would move the dragnet to the telecoms.

The reauthorization signed the following day — dated March 28, 2014 — eliminated all approval for automated queries.

I suggested then — and given these stories, suspect may have been correct — that Obama agreed to move the dragnet to the telecoms because NSA never managed to do what they wanted to do (and probably, had done until 2009), automated queries, but they could achieve the same desired result by moving production to the telecoms.

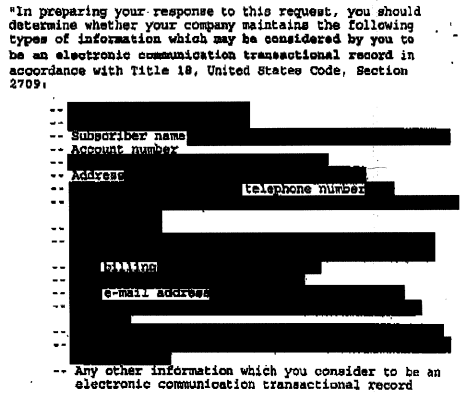

All proposed plans to move production to the telecoms shared several features, including the compelled assistance of the telecoms (like Section 702, in some ways), production of records in the form the government wanted, expansive immunity, and compensation. All also used “connection chaining” that didn’t explicitly describe what made a (non-call or text) connection or how the telecom would establish such connections. I speculated last year that may have permitted the government to make use of the telecoms’ access to geolocation in a way they couldn’t do at NSA. I increasingly believe they also want telecoms to match all chaining through smart phones in what they’ve adopted as “connection chaining;” automated correlations, specifically, is something the government shut down in 2009 but which would be very productive if it could draw on everything the telecoms have.

None of that explains why the NSA wasn’t able to ingest some cell phone production. But it may explain why NSA accepts moving the phone dragnet to the telecoms.