I’m going to make an unpopular argument.

Most observers of USA F-ReDux point to weakened transparency provisions as one of the biggest drawbacks of the latest version of the bill. They’re not wrong: transparency procedures are worse, remarkably so.

But given that I already thought they were not only inadequate but dangerously misleading,* I’m actually grateful to have had the Intelligence Community do another version of transparency provisions, which shows what they’re most intent on hiding and/or hints at what they will really be doing behind the carefully scripted words they’re getting Congress to rubber-stamp.

For comparison, I’ve put the bulk of the required transparency provisions for USA F-ReDux and Leahy’s USA Freedom below the rules below.

Hiding how 702 numbers will explode

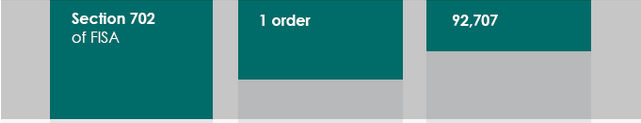

The most remarkable of the changes in the transparency provision is that they basically took out this language requiring a top level count of Section 702 targets and persons whose communications were affected — this language.

(i) the number of targets of such orders;

(ii) the number of individuals whose communications were collected pursuant to such orders; [sub 500 range]

(iii) the number of individuals whose communications were collected pursuant to such orders who are reasonably believed to have been located in the United States at the time of collection; [sub 500 range]

This leaves — in addition to the “number of 702 orders” requirement — just this reporting requirement for back door content and metadata searches which (like the Leahy bill) exempts the gross majority of the back door searches, because they are done by the FBI.

(A) the number of search terms concerning a known United States person used to retrieve the unminimized contents of electronic communications or wire communications obtained through acquisitions authorized under such section, excluding the number of search terms used to prevent the return of information concerning a United States person; and [FBI Exemption]

(B) the number of queries concerning a known United States person of unminimized noncontents information relating to electronic communications or wire communications obtained through acquisitions authorized under such section, excluding the number of queries containing information used to prevent the return of information concerning a United States person; [FBI Exemption]

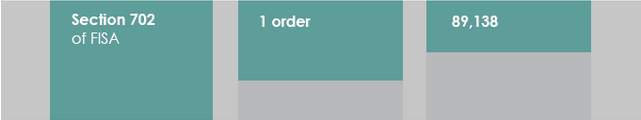

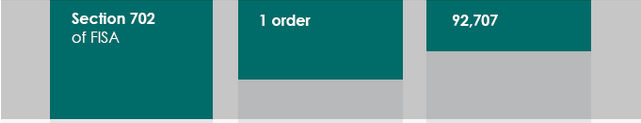

This is all the more remarkable given that ODNI has given us the topline number (though not the number of people sucked in) in each of its last two transparency reports.

In other words, ODNI was happy to tell us that the number of FISA 702 targets went up by 4% between 2013 and 2014, but not how much those numbers of targets will go up in 2015, when they presumably begin to roll out the new call chaining provision.

I suspect — and these are well educated but nevertheless wildarseguesses — there are several reasons.

The number of unique identifiers collected under 702 is astronomical

First, the reporting provisions as a whole move from tracking “individuals whose communications were collected” to “unique identifiers used to communicate information.” They probably did that because they don’t really have a handle on which of the identifiers all represent the same natural person (and some aren’t natural persons), and don’t plan on ever getting a handle on that number. Under last year’s bill, ONDI could certify to Congress that he couldn’t count that number (and then as an interim measure I understand they were going to let them do that, but require a deadline on when they would be able to count it). Now, they’ve eliminated such certification for all but 702 metadata back door searches (that certification will apply exclusively to CIA, since FBI is exempted). In other words, part of this is just an admission that ODNI does not know and does not planning on knowing how many of the identifiers they target actually fit together to individual targets.

But since they’re breaking things out into identifiers now, I suspect they’re unwilling to give that number because for each of the 93,000 targets they’re currently collecting on, they’re probably collecting on at least 10 unique identifiers and probably usually far, far more.

Just as an example (this is an inapt case because Hassanshahi, as a US person, could not be a PRISM target, but it does show the bare minimum of what a PRISM target would get), the two reports Google provided in response to administrative subpoenas for information on Shantia Hassanshahi, the guy caught using the DEA phone dragnet (these were subpoenas almost certainly used to parallel construct data obtained from the DEA phone dragnet and PRISM targeted at the Iranian, “Sheikhi,” they found him through), included:

- a primary gmail account

- two secondary gmail accounts

- a second name tied to one of those gmail accounts

- a backup email (Yahoo) address

- a backup phone (unknown provider) account

- Google phone number

- Google SMS number

- a primary login IP

- 4 other IP logins they were tracking

- 3 credit card accounts

- Respectively 40, 5, and 11 Google services tied to the primary and two secondary Google accounts, much of which would be treated as separate, correlated identifiers

So just for this person who might be targeted under the new phone dragnet (though they’d have to play the same game of treating Iran as a terrorist organization that they currently do, but I assume they will), you’d have upwards of 15 unique identifiers obtained just from Google. And that doesn’t include a single cookie, which I’ve seen other subpoenas to Google return.

In other words, one likely reason the IC has decided, now that they’re going to report in terms of unique identifiers, they can’t report the number of identifiers targeted under PRISM is because it would make it clear that those 93,000 targets represent, very conservatively, over a million identifiers — and once you add in cookies, maybe a billion identifiers — targeted. And reporting that would make it clear what kind of identifier soup the IC is swimming in.

Hiding new PRISM providers

There is another reason I think they’ve grown reluctant to show much transparency under 702. Implementing the USA F-ReDux system — in which each provider sets up facilities they can use to chain on non-call detail record session identifying information — means more providers (smaller phone companies, and some new Internet providers, for example) will have what amount to PRISM-lite portals that can also be used for PRISM production. If you build it they will come!

In addition, Verizon and Sprint may be providing more PRISM smart phone materials in addition to upstream collection (AT&T likely already provides a lot of this because that’s how they roll).

So I suspect that, whereas now there’s a gap between the cumulative numbers providers report in their own transparency reports and what we see from ODNI, that number will grow notably, which would lead to questions about where the additional 702 production was coming from. (Until Amazon starts producing transparency reports, though, I’ll just assume they’re providing it all).

Hiding the smart-phone-PRISM

Finally, I think that once USA F-ReDux rolls out, the government (read, FBI, where this data will first be sucked in) will have difficulty distinguishing between the 702 and 215 production from a number of providers — probably AT&T, Verizon, Apple, Google, and Microsoft, but that’s just a guess.

Going back to the case of Hassanshahi, for example (and assuming, as I do, that the government has been parallel constructing the fact that they also targeted the Iranian Sheikhi identifier under PRISM, which would have immediately led them to his GMail account, as they very very easily could), the Tehran phone to Google call between Sheikhi and Hassanshahi would likely come in via at least 3 sources: Sheihki PRISM collection, Google USA F-ReDux returns on the Sheikhi number, and AT&T backbone USA F-ReDux returns on the Sheikhi number. And all that’s before you’ve taken a single hop into Hassanshahi’s accounts.

In other words, what you’re actually getting with USA F-ReDux is a way to get to the metadata of US persons identified via incidental collection under PRISM (again, this should just before for targets of a somewhat loosey goosey definition of terrorism targets). It’s basically a way to get a metadata “hop” off of all the Americans already “incidentally” collected under PRISM (note, permission to do this for targets identified under a probable cause warrant is already written into every phone dragnet order; this just extends that, with FISC review, to PRISM targets). And for the big providers that have anything that might be considered “call” service, the portals from which that will derive will likely be very very closely related.

Read more →