BREAKING: What emptywheel Reported Two Years Ago

The NYT today:

The National Security Agency has used its bulk domestic phone records program to search for operatives from the government of Iran and “associated terrorist organizations” — not just Al Qaeda and its allies — according to a document obtained by The New York Times.

[snip]

The inclusion of Iran and allied terrorist groups — presumably the Shiite group Hezbollah — and the confirmation of the names of other participating companies add new details to public understanding of the once-secret program. The Bush administration created the program to try to find hidden terrorist cells on domestic soil after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and government officials have justified it by using Al Qaeda as an example.

emptywheel, 15 months ago:

I want to post Dianne Feinstein’s statement about what Section 215 does because, well, it seems Iran is now a terrorist. (This is around 1:55)

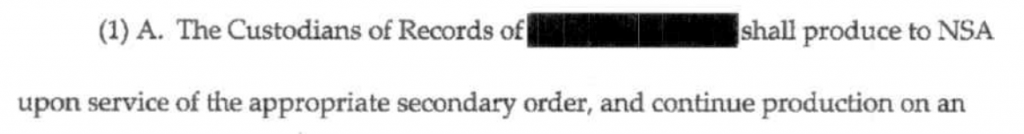

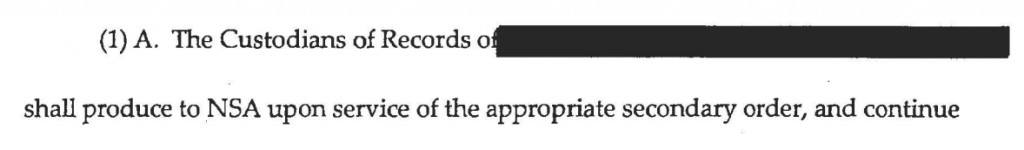

The Section 215 Business Records provision was created in 2001 in the PATRIOT for tangible things: hotel records, credit card statements, etcetera. Things that are not phone or email communications. The FBI uses that authority as part of its terrorism investigations. The NSA only uses Section 215 for phone call records — not for Google searches or other things. Under Section 215, NSA collects phone records pursuant to a court record. It can only look at that data after a showing that there is a reasonable, articulable that a specific individual is involved in terrorism, actually related to al Qaeda or Iran. At that point, the database can be searched. But that search only provides metadata, of those phone numbers. Of things that are in the phone bill. That person, um [flips paper] So the vast majority of records in the database are never accessed, and are deleted after a period of five years. To look at, or use content, a court warrant must be obtained.

Is that a fair description, or can you correct it in any way?

Keith Alexander: That is correct, Senator. [underline/italics added]

Some time after this post Josh Gerstein reported on Keith Alexander confirming the Iran targeting.

The NYT today:

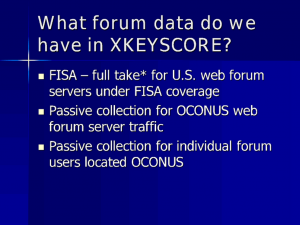

One document also reveals a new nugget that fills in a timeline about surveillance: a key date for a companion N.S.A. program that collected records about Americans’ emails and other Internet communications in bulk. The N.S.A. ended that program in 2011 and declassified its existence after the Snowden disclosures.

In 2009, the N.S.A. realized that there were problems with the Internet records program as well and turned it off. It then later obtained Judge Bates’s permission to turn it back on and expand it.

When the government declassified his ruling permitting the program to resume, the date was redacted. The report says it happened in July 2010.

emptywheel in November 2013:

I’ve seen a lot of outright errors in the reporting on the John Bates opinion authorizing the government to restart the Internet metadata program released on Monday.

Bates’ opinion was likely written in July 2010.

[snip]

It had to have been written after June 21, 2010 and probably dates to between June 21 and July 23, 2010, because page 92 footnote 78 cites Holder v. HLP (which was released on June 21), but uses a “WL” citation; by July 23 the “S. Ct.” citation was available. (h/t to Document Exploitation for this last observation).

So: it had to have been written between June 21, 2010 and October 3, 2011, but was almost certainly written sometime in the July 2010 timeframe.

The latter oversight is understandable, as this story — which has been cited in court filings — misread Claire Eagan’s discussions of earlier bulk opinions, which quoted several sentences of Bates’ earlier one (though it was not the among the stories that really botched the timing of the Bates opinion).

In September, the Obama administration declassified and released a lengthy opinion by Judge Claire Eagan of the surveillance court, written a month earlier and explaining why the panel had given legal blessing to the call log program. A largely overlooked passage of her ruling suggested that the court has also issued orders for at least two other types of bulk data collection.

Specifically, Judge Eagan noted that the court had previously examined the issue of what records are relevant to an investigation for the purpose of “bulk collections,” plural. There followed more than six lines that were censored in the publicly released version of her opinion.

There have been multiple pieces of evidence to confirm my earlier July 2010 deduction since.

The big news in the NYT story (though not necessarily the NYT documents, which I’ll return to) is that in 2010, Verizon Wireless also received phone dragnet orders. I’ll return to what that tells us too.

But the news that Iran was targeted under the phone dragnet was confirmed publicly — and reported here — in a prepared statement from the Senate Intelligence Chair and confirmed by the Director of National Security Agency a week after the first Snowden leak story.