Stingrays and Public Safety Operations

In my piece on the loopholes in the new Stingray policy, I noted that public safety applications for Stingray use might fall under what the policy calls the “exceptional circumstances” that aren’t exigent but nevertheless don’t require a warrant.

I’m not sure whether the exigent/emergency use incorporates the public safety applications mentioned in the non-disclosure agreements localities sign with the FBI, or if that’s included in this oblique passage.

There may also be other circumstances in which, although exigent circumstances do not exist, the law does not require a search warrant and circumstances make obtaining a search warrant impracticable. In such cases, which we expect to be very limited, agents must first obtain approval from executive-level personnel at the agency’s headquarters and the relevant U.S. Attorney, and then from a Criminal Division DAAG. The Criminal Division shall keep track of the number of times the use of a cell-site simulator is approved under this subsection, as well as the circumstances underlying each such use.

In short, many, if not most, known uses are included in exceptions to the new policy.

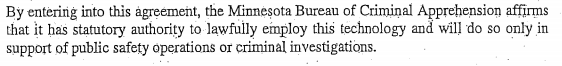

We know there are public safety applications, because they are permitted even to localities by FBI’s Non-Disclosure Agreements.

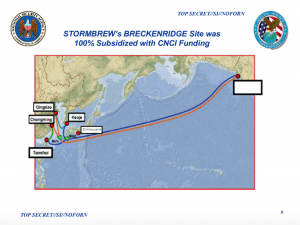

I suspect these uses are for public events to both track the presence of known targets and to collect who was present in case of any terrorist event or other serious disruption. Indeed, for a lot of reasons — notably the odd testimony of FBI’s telecom forensics witness, the way FBI’s witnesses were bracketed off from investigators, and some oddness about when and how they found the brothers’ phones (and therefore the brothers) — I suspect someone was running Stingrays at the Boston Marathon. A Stingray (or many) deployed at public events to help protect them (assuming, of course, the terrorists that attack such an event aren’t narcs for the DEA, as people have speculated Tamerlan Tsarnaev was).

Newsweek asked DOJ whether that exceptional circumstances paragraph covered the use of Stingrays in public places included in a policy released by the FBI in December and they confirmed it is (here’s my post on the December release, which anticipates all the loopholes in the policy I IDed the other day).

In December 2014, the FBI, which falls under Justice Department’s new policy, explained to members of Congress the situations in which it does not need a warrant to deploy the technology. They include: “(1) cases that pose an imminent danger to public safety, (2) cases that involve a fugitive, or (3) cases in which the technology is used in public places or other locations at which the FBI deems there is no reasonable expectation of privacy.”

Newsweek reached out to the Justice Department to determine whether its new policy allows the FBI to continue using stingrays without warrants in public places. In short, it does, fitting within the policy’s “exceptional circumstances” category.

“If somebody is in a public park, that is a public space,” Patrick Rodenbush, a Justice Department spokesman, says as an example, adding the condition that “circumstances on the ground make obtaining a warrant impracticable,” though he did not elaborate on what “impracticable” entails. But the dragnet nature of stingray collection means cellphone data of a person sitting in a nearby house may be picked up as well. “That’s why we have the deletion policy that we do,” Rodenbush responds. “In some cases it’s everyday that [bystander information] is deleted, it depends what they are using it for.… In some cases it is a maximum of 30 days.”

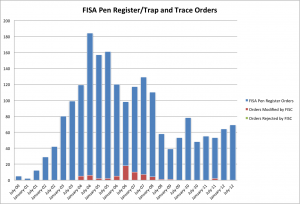

He adds: “The circumstances under which this exception will be granted will be very limited. Agents operating under this exception are still required to obtain a court order pursuant to the Pen Register Statute, and comply with the policy’s requirements to obtain senior-level department approval.”

Equally important as admitting that DOJ will use this in public places (like big sporting events) is Rodenbush’s confirmation that DOJ will obtain only Pen Registers for these uses.

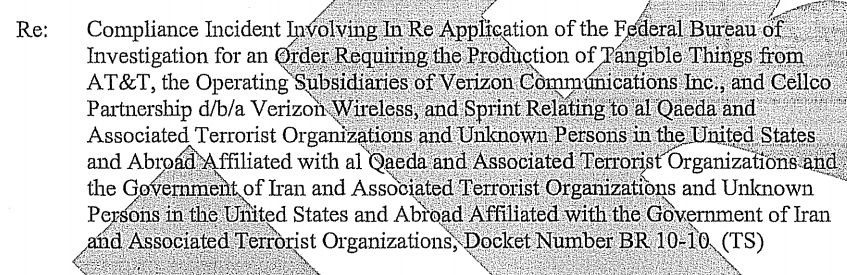

That means they’ll virtually never get noticed to defendants, because the government will claim the evidence did not get introduced in court (just as no evidence collected from a Stingray was introduced, if they were used, in Dzhokhar’s case; in Dzhokhar’s case there was always another GPS device that showed his location).

The more I review this new policy and the December one the more I’m convinced they change almost nothing except the notice to the judge and the minimization (both still important improvements), except insofar as they recreate ignorance of Stingray use precisely in cases like public safety operations.