On November 24, Judge Michael Mosman approved the government’s request to hold onto the Section 215 phone dragnet data for technical assurance purposes for three months, as well as to hold the data to comply with a preservation order in EFF’s challenge to the phone dragnet (though as with one earlier order in this series, Thomas Hogan signed the order for Mosman, who lives in Oregon). While the outcome of the decision is not a surprise, the process bears some attention, as it’s the first time a truly neutral amicus has been involved in the FISC process (though corporations, litigants, and civil rights groups have weighed in various decisions as amici).

In addition to Mosman’s opinion, the FISC released amicus Preston Burton’s memo and the government’s response on December 2; I suspect there may be a Burton reply they have not released.

Minimization procedures

As I noted in September when Mosman first appointed Burton, it wasn’t entirely clear what the FISC was asking him to review. In his order, Mosman explains that he “directed him to address whether the government’s above-described requests to retain and use BR metadata after November 28, 2015, are precluded by section 103 of the USA FREEDOM Act or any other provision of that Act.”

Burton took this to be largely a question about minimization procedures.

Instead, the Act provides that the Court shall decide issues concerning the use, retention, dissemination, and eventual destruction of the tangible things collected under the FISA business records statute as part of its oversight of the statutorily mandated minimization procedures.

He then pointed to a number of the FISC’s more assertive oversight moments over the NSA to argue that the FISC has fairly broad authorities to review minimization procedures.

Although the government is required to enumerate minimization procedures addressing the use, retention, dissemination, and (now) ultimate destruction of the metadata in its applications to the Court, the Court’s review of those procedures is not simply ministerial. And, indeed, Judge Walton’s 2009 orders, cited above, addressing deficiencies in the administration of the call detail record program made clear that the FISA Court may impose more robust minimization procedures. See also Kris, Bulk Collection at 15-17 (discussing FISA Court’s imposition of new restrictions to the telephony program). Likewise, the Court may decline to endorse procedures sought by the government See Opinion at 11-2, In re Application of the FBI for an Order Requiring the Production of Tangible Things, Docket No. BR 14-01 (March 7, 2014) (denying the government’s motion to modify the minimization procedures), amended, Opinion at S, Jn re Application of the FBI/or an Order Requiring the Production a/Tangible Things, Docket No. BR 14-01(March12, 2014). Similarly, Judge Bates found substantial deficiencies in the NSA’ s minimization procedures in Jn Re [Redacted}, 2011 WL l 0945618, at *9 (FISA Ct. Oct. 3, 2011) (Bates J.) (fmding NSA minimization procedures insufficient and inconsistent with the Fourth Amendment). As a result, the NSA amended its procedures, including reducing the data retention in issue in that case (under a differentFISA statute) from five to two years. See In Re [Redacted], 2011WL10947772, at •s (FISA Ct. Nov. 30, 2011) (Bates J.).

Particularly in the case of the two PRTT orders, the government has actually challenged FISC’s roles in imposing minimization procedures (though admittedly FISC’s role under that authority is less clear cut than under Section 215).

Burton argued that USA Freedom Act (which he abbreviated USFA) made that role even stronger.

But the USFA augmented this minimization review authority even more and dispels any suggestion that the Court may not modify the minimization procedures articulated in the government’s application. The statute’s fortification of Judicial Review provisions makes clear that Congress intended for the FISA Court to oversee these issues in the context of imposing minimization procedures that balance the government’s national security interests with privacy interests, including specifically providing for the prompt destruction of tangible things produced under the business records provisions.10 Significantly, USF A § 104 empowers the Court to assess and supplement the government’s proposed minimization procedures:

Nothing in this subsection shall limit the authority of the court established under section 103(a) to impose additional, particularized minimization procedures with regard to the production, retention, or dissemination of nonpublicly available information concerning unconsenting United States persons, including additional particularized procedures related to the destruction of information within a reasonable time period. USFA § 104 (a)(3) (now codified at 50 U.S.C. §1861(g)(3)(emphasis supplied).

That provision applies to all information the government obtains under the business records procedure, not just call detail records. u Moreover, that amendment, set forth in USFA § 104, went into effect immediately, unlike the 180-day transition period for the revisions to the business records sections. See USFA § 109 (amendments made by §§ 101-103 take effect 180 days after enactment).12

As I said, that’s the kind of argument the government has been arguing against for 11 years, most notably in the two big Internet dragnet reauthorizations (admittedly, FISC’s role in minimization procedures there is less clear, but there is similar language about not limiting the authority of the court).

Burton sneaks in some real privacy questions

Having laid out the (as he sees it) expansive authority to review minimization procedures, Burton then does something delightful.

He poses a lot of questions that should have been asked 9 years ago.

Because of the significant privacy concerns that motivated Congress to amend the bulk collection provisions of the statute, however, the undersigned respectfully submits that, the Court should consider requiring the government to answer more fully fundamental questions regarding:

- The current conditions, location, and security for the data archive.

- The persons and entities to whom the NSA has given access to information provided under this program and whether that shared information will also be destroyed under the NSA destruction plan (and, if not, why not?).

- What oversight is in place to ensure that access to the database is not “analytical” and what the government means by “non-analytical.”

- Why testing of the adequacy of new procedures was not completed by the NSA (and whether it was even initiated) during the 180-day transition period.

- How the government intends to destroy such information after February 29, 2016, (its proposed extinction date for the database) independent of the resolution of any litigation holds.

- Whether the contemplated destruction will include only data that the government has collected or will include all data that it has analyzed in some fashion.

Remember, by the time Burton wrote this, he had read at least the application for the final dragnet order, and the answers to these questions were not clear from that (which is where the government lays out its more detailed minimization procedures). Public releases have made me really concerned about some of them, such as how to protect non-analytical queries from being used for analytical purposes. NSA has had tech people do analytical queries in the past, and it doesn’t audit tech activities. Similarly, when the NSA destroyed the Internet dragnet data in 2011, NSA’s IG wasn’t entirely convinced it all got destroyed, because he couldn’t see the intake side of things. So these are real issues of concern.

Burton also asked questions about the necessity behind keeping data for the EFF challenges rather than just according the plaintiffs standing.

If this Court chooses to follow Judge Walton’s approach and defer to the preservation orders issued by the other courts, the Court nonetheless should address a number of questions before deciding whether to grant the government’s preservation request:

- Why has the government been unable to reach some stipulation with the plaintiffs to preserve only the evidence necessary for plaintiffs to meet their standing burden? Consider whether it is appropriate for the government to retain billions of irrelevant call detail records involving millions of people based on, what undersigned understands from counsel involved in that litigation, the government’s stubborn procedural challenges to standing — a situation that the government has fostered by declining to identify the particular telecommunications provider in question and/or stipulate that the plaintiff is a customer of a relevant provided.

- As Judge Walton identified when he first denied the modification of the minimization procedures to extend the duration of preservation, the continued retention of the data at issue subjects it to risk of misuse and improper dissemination. The government should have to satisfy the Court of the security of this information in plain and meaningful terms.

(Notice how he assumes the plaintiffs might have standing which, especially for First Unitarian Church plaintiff CAIR, they should.)

Finally, perhaps channeling the justified complaint of all the tech people who review these kinds of policy questions, Burton suggested the FISC really ought to be consulting with a tech person.

This case, due to the relatively limited period of time sought by the government to accomplish its stated narrow purpose, likely does not require a difficult assessment of the reasonableness of the government’s technical retention request. To evaluate even such a limited request, however, the Court may wish to consider availing itself of technical expertise from national security experts or computer technology experts. Technical expertise is an amicus category contemplated by Congress in its reform of the FISA statutes. 50 U.S.C. § 1803 (i)(2)(B), as amended by USF A Section 401. That section alone suggests congressional expectation of greater judicial oversight of the government’s surveillance program and requests. See USF A § 401; see also Kris, Bulk Collection at 3 7 (contemplating theoretical procedures for cross-examining NSA engineers as one example of the challenges in implementing a more adversarial system for the FISA Court).

Burton ended his memo reiterating his recommendation that FISC get more information.

In light of the significant privacy interests affected by the creation and retention of the database, the undersigned urges the Court as part of its statutory oversight of the minimization procedures to demand full and meaningful information concerning the condition of the data at issue, the data’s security, and its contemplated destruction as a condition of any retention beyond November 28, 2015.

The government is not amused

Predictably, the government balked at Burton’s invitation to use his expansive reading of the authority of the FISC to review minimization procedures to bolster the current ones.

Amicus curiae’ s analysis of Section 104 of the USA FREEDOM Act could be interpreted as suggesting an opportunity for the Court to re-examine the minimization procedures applicable for other business records productions in this proceeding. Consistent with the Court’s order appointing amicus curiae, the Government has limited its response to the issue identified in that order.

Frankly, I’m not sure what the government distinguishes between Burton’s proposal to reexamine existing minimization procedures and what is covered by the order in question, because they do respond to a number of the questions he raised in his brief.

For example, they provide these details about where the dragnet lives (which, as it turns out, is at Fort Meade, not the UT data center).

As described in the Application in docket number BR 15-99 and prior docket numbers, NSA stores and processes the bulk call detail records in repositories within secure networks under NSA’ s control. Those repositories (servers, networked storage devices, and backup tapes in locked containers) are located in NSA’s secure, access-controlled facilities at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland. As further described in those applications, NSA restricts access to the records to authorized personnel who have received appropriate and adequate training. Electronic access to the call detail records requires a user authentication credential. Physical access to the location where NSA stores and processes the call detail records requires an approval by NSA management and must be conducted in teams of no less than two persons.

Also note that there is currently a requirement that techs access the raw data in two person teams. That is likely a change that post-dates Snowden.

Curiously, the NSA says they can destroy all the phone dragnet data in a month.

NSA anticipates it can complete destruction of the bulk call detail records and related chain summaries within one month of being relieved of its litigation preservation obligations.

They appear to have taken far less time to destroy the Internet dragnet data, further supporting the appearance they did it very hastily to avoid having to report back to John Bates on the status of their dragnet.

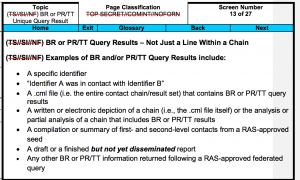

Finally, they make clear what had already been clear to me: the existing query results will remain at NSA.

Information obtained or derived from call detail records which has been previously disseminated in accordance with approved minimization procedures will not be recalled or destroyed.2 Also, select query results generated by pre-November 29, 2015, queries of the bulk records that formed the basis of a dissemination in accordance with approved minimization procedures will not be destroyed.

2 This practice does not differ from similar circumstances where, for example Court-authorized electronic surveillance and/or physical search authorities under Title I or III expire. While raw (unminimized) information is handled and destroyed in accordance with applicable minimization procedures, prior authorized disseminations and the material underpinning those disseminations are not recalled or otherwise destroyed.

This means that everyone within two or three degrees of a target that the NSA has found interesting — potentially over the last decade — will remain available and subject to NSA’s analytical toys from here on out.

Let’s hope CAIR gets standing to challenge what has happened to their IDs then.

Which may be why the government gets snippiest in response to Burton’s question about why they’re going to keep billions of phone records rather than just reach some accommodation with EFF.

The suggestions by amicus curiae that this Court address (or perhaps even resolve) significant substantive questions at issue in underlying civil litigation,, see Amicus Mem. of Law at 27, are exactly the kinds of inquiries the Court previously recognized were inappropriate for it to resolve. Opinion and Order, docket number BR 14-01at5 (“it is appropriate for [the district court for the Northern District of California], rather than the FISC, to determine what BR metadata is relevant to that litigation”). This Court should adopt the same view. In particular, the suggestion that the Government disclose national security information concerning the identity of providers, information subject to a pending state secrets privilege assertion, is inappropriate, and the suggestion by amicus that the government stipulate to Article III standing in those cases is unfounded as a matter of law. Finally, the suggestion that preservation of bulk call detail records can be limited solely to the plaintiffs in multiple pending putative class actions is entirely unworkable. For the reasons more particularly set out above, until the Government is relieved of its preservation obligations, the data is secure.

Which leads me to the detail that makes me suspect there’s a second Burton filing the government hasn’t released (I’ve asked NSD but gotten no answer, and in his opinion Mosman says only “Mr. Burton and the government submitted briefs addressing this question,” leaving open the possibility Burton submitted two): After finding no reason to hold a hearing on the issue of restarting the dragnet during the summer, Mosman did hold a hearing here (though it’s not clear whether Burton attended or not). At the hearing, Mosman ordered the government to try to come up with a way to destroy the dragnets, which it will do by January 8.

During the hearing held on November 20, 2015, the Court directed the government to submit its assessment of whether the cessation of bulk collection on November 28, 2015, will moot the claims of the plaintiffs in the Northern District of California litigation relating to the BR Metadata program and thus provide a basis for moving to lift the preservation orders. The Court further directed the government to address whether, even if the California plaintiffs’ claims are not moot, there might be a basis for seeking to lift the preservation orders with respect to the BR Metadata that is not associated with the plaintiffs. The government intends to make its submission on these issues by January 8, 2016.

And, as Mosman’s opinion makes clear, he ordered them to write up a free-standing copy of the minimization procedures that will govern the dragnet data retained from here on out.

The minimization procedures that the government proposes using after the production ceases on November 28, 2015 are in important respects substantially more restrictive than those currently in effect. The procedures that will apply after November 28, which were initially included as part of the broader set of procedures set forth in the application, were resubmitted by the government in a standalone document on November 24, 2015 (“November 24, 2015 Minimization Procedures”).

They would have submitted them on the day Mosman (via Hogan’s signature) approved the request to keep the data. In other words, Mosman made the government generate a document to make it crystal clear the more restrictive rules apply to the dragnet going forward.

The value of the amicus

Whether it was Mosman’s intent when he appointed Burton or not (remember, for better and worse, under USAF the amicus has to do what the FISC asks), his appointment served several purposes.

First, it set Mosman up to make it very clear that the FISC sees the minimization procedures required under USAF do give the FISC expanded authority.

The USA FREEDOM Act made several minimization-related changes to Section 1861. For instance, Section 1861 now provides that, before granting a business records application, the Court must expressly find that the minimization procedures put forth by the government “meet the definition ofminimiz.ation procedures under subsection (g).” See Pub. L. No. 114-23, § 104(a)(l), 129 Stat. at 272. This change is not substantive, however, as such a finding was previously implicit in the broader finding required by Section 1861 ( c )(1) – i.e, “that the application meets the requirements of subsection (a) and (b).” Among the requirements of subsection (b) was – and still is – the requirement that the application include an enumeration of Attorney General-approved minimization procedures that meet the definition set forth in subsection (g). Another change is the addition of a “rule of construction” confirming the Court’s authority “to impose additional, particularized minimization procedures with regard to the production, retention, or dissemination” of certain information regarding United States persons, including “procedures related to the destruction of information within a reasonable time period.” See id. § 104(a)(2), 129 Stat. at 272. A third new provision that takes effect on November 29, 2015, states that orders compelling the ongoing, targeted production of “call detail records” must direct the government to adopt minimization procedures containing certain requirements relating to the destruction of such records. See id Pub. L. No. 114-23, § 10l(b)(3)(F)(vii), 129 Stat. at 270-71.

Remember, it took 7 years — including 4 years of FISC-imposed minimization requirements and reviews — before the government met the requirements of the law as passed in 2006. Significantly, Burton got a classified version of the IG report laying out that delay to read, so he surely knows more about that delay than we do.

In addition, Burton set up the FISC to demand more assurances from the government and — potentially — to push it to come to some more reasonable accommodation with EFF than they otherwise might. Remember, when presiding over the criminal case of Raez Qadir Khan, Mosman was going to grant CIPA discovery on the surveillance used to catch Khan, some of which almost certainly included one (Stellar Wind) or another (the PRTT Internet dragnet) of the illegal dragnets, which led almost immediately to a plea deal.

I’m, frankly, pleasantly surprised. Whether it was Mosman’s intent or not, even picking someone without an obvious brief for privacy, Burton helped Mosman shore up the authority of the FISC to ride herd over government spying (and given Judge Hogan’s involvement along the way, he presumably did so with the assent of the presiding FISC judge).

In any case, Mosman was happy with how it all worked out, as he included this footnote in his opinion.

The Court wishes to thank Mr. Burton for his work in this matter. His written and oral presentations were extremely informative to the Court’s consideration of the issues addressed herein. The Court is grateful for his willingness to serve in this capacity.

John Bates, speaking inappropriately on behalf of the FISA Court during USAF debates, squealed mightily about the role an amicus had. Admittedly, the current form is closer to what Bates (who I’ve always suspected was speaking on behalf of John Roberts more than the court) wanted than what reformers wanted.

But at least in this instance, the amicus helped the FISC shore up its authority vis a vis the government.

Update: Richard Posey notes the reference to Burton’s “oral” presentations in the thank you footnote, which suggests he was at the November 20 hearing. Read more →