Ben Wittes’ Delusion: FBI IS the Intelligence Community

Ben Wittes has started a series of posts on how to tyrant-proof the presidency. His first post argues that Jennifer Granick’s worries about surveillance and Conor Friedersdorf’s worries about drone-killing are misplaced. The real risk, Wittes argues, comes from DOJ.

What would a president need to do to shift the Justice Department to the crimes or civil infractions committed—or suspected—by Trump critics and opponents? He would need to appoint and get confirmed by the Senate the right attorney general. That’s very doable. He’d want to keep his communications with that person limited. An unspoken understanding that the Justice Department’s new priorities include crimes by the right sort of people would be better than the sort of chortling communications Richard Nixon and John Mitchell used to have. Want to go after Jeff Bezos to retaliate for the Washington Post‘s coverage of the campaign? Develop a sudden trust-busting interest in retailers that are “too big”; half the country will be with you. Just make sure you state your non-neutral principles in neutral terms.

[snip]

There are other reasons to expect a politically abusive president to focus on the Justice Department and other domestic, civilian regulatory and law enforcement agencies: one is that the points of contact between these agencies and the American people are many, whereas the population’s points of contact with the intelligence community are few. The delusions of many civil libertarians aside, the intelligence community really does focus its activities overseas. To reorient it towards domestic oppression would take a lot of doing. It also has no legal authority to do things like arresting people, threatening them with long prison terms, fining them, or issuing subpoenas to everyone they have ever met. By contrast, the Justice Department has outposts all over the country. Its focus is primarily domestic. It issues authortitative legal guidance within the executive branch to every other agency that operates within the country. And it has the ability to order people to produce material and testify about whatever it wants to investigate.

What’s more, when it receives such material, it is subject to dramatically laxer rules as to its use than is the intelligence community. Unlike, say, when NSA collects material under Section 702, when the Justice Department gets material under a grand jury subpoena, there aren’t a lot of use restrictions (other than Rule 6(e)’s prohibition against leaking it); and there is no mandatory period after which DOJ has to destroy it. It has countless opportunities, in other words, to engage in oppressive activities, and it is largely not law but norms and human and institutional decency that constrain it.

I don’t necessarily disagree with the premise. Indeed, I’ve argued it for years — noting, for example, that a targeted killing in the US would look a lot more like the killing of Imam Luqman Abdullah in 2009 (or the killing of Fred Hampton in 1969) than drone killing of Anwar al-Awlaki in 2011 (given that Abdullah’s selling of stolen items got treated as terrorism in part because of his positive statements about Awlaki, it is not inconceivable FBI started infiltrating his mosque because of SIGINT).

My gripe (I have to have gripes because it is Wittes) is on two points. First, Wittes far overestimates how well the protections against abuse currently work. He seems to believe the Levi Guidelines remain in place unchanged, that the 2008 and 2011 and serial secret changes to the Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide since then have not watered down limits on investigations for protected activities. He suggests it was a good thing to use prosecutorial discretion to chase drugs in the 1990s and terrorism in the 2000s, and doesn’t consider why the rich donors who’ve done as much damage as terrorists to the country — the banksters, even those that materially supported terrorists — have gotten away with wrist-slap fines. It was not a good thing to remain obsessed with terrorists while the banksters destroyed our economy through serial global fraud (a point made even by former FBI agents).

We already have a dramatically unequal treatment of homegrown extremists in this country based on religion (compare the treatment of the Malheur occupiers with that of any young Muslim guy tweeting about ISIS who then gets caught in an FBI sting). We already treat Muslims (and African Americans and — because we’re still chasing drugs more than we should — Latinos) differently in this country, even though the guy running for President on doing so as a campaign plank isn’t even in office yet!

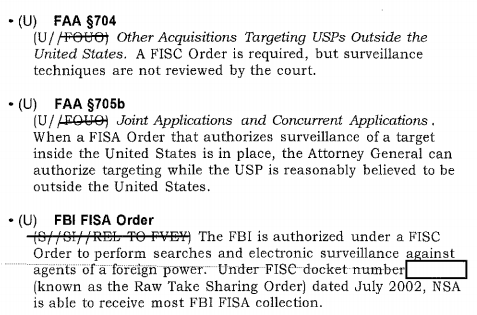

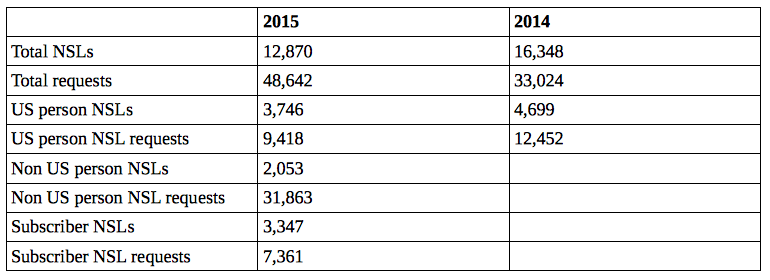

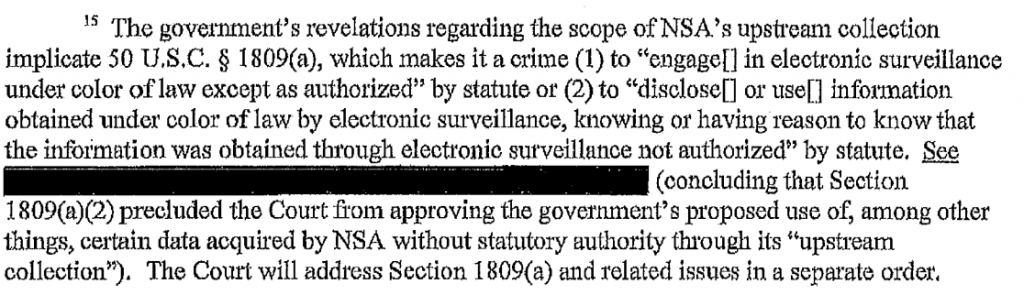

The other critical point Wittes missed in his claim that “delusional” civil libertarians don’t know that “the intelligence community really does focus its activities overseas” is that DOJ, in the form of FBI and DEA, is the Intelligence Community, and their intelligence focus is not exclusively overseas (nor is the intelligence focus of other IC members DHS — which has already surveilled Black Lives Matter activists — and Treasury). The first dragnet was not NSA’s, but the DEA one set up under Bill Clinton. One big point of Stellar Wind (which is what Wittes mocked Granick for focusing on) was to feed FBI tips of people the Bureau should investigate, based solely on their associations. And while Wittes is correct that “when the Justice Department gets material under a grand jury subpoena, there aren’t a lot of use restrictions (other than Rule 6(e)’s prohibition against leaking it); and there is no mandatory period after which DOJ has to destroy it,” it is equally true of when FBI gets raw 702 data collected without grand jury scrutiny.

FBI can conduct an assessment to ID the racial profile of a community with raw 702 data, it can use it to find and coerce potential informants, and it can use it for non-national security crimes. That’s the surveillance Wittes says civil libertarians are delusional to be concerned about, being used with inadequate oversight in the agency Wittes himself says we need to worry about.

Four different times in his post, Wittes contrasts DOJ with the intelligence community, without ever considering what it means that DOJ’s components FBI and DEA are actually part of it, that part of it that takes data obtained from NSA’s surveillance and uses it (laundered through parallel construction) against Americans. You can’t contrast the FBI’s potential impact with that of the IC as Wittes does, because the FBI is (one of) the means by which IC activities impact Americans directly.

Yes, DOJ is where President Trump (and President Hillary) might abuse their power most directly. But in arguing that, Wittes is arguing that the President can use the intelligence community abusively.