More Thoughts on the Yahoo Scan

I want to lay out a few more thoughts about the still conflicting stories about the scan the government asked Yahoo to do last year.

The three different types of sources and their agenda

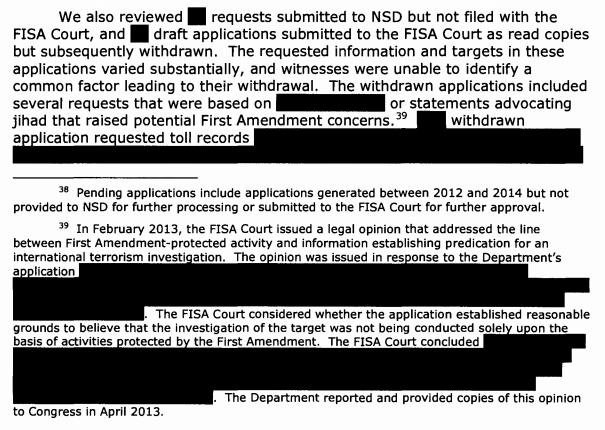

First, a word about sourcing. The original three stories have pretty identifiable sources. The first Reuters story, by tech security writer Joseph Menn and describing the scan as “a program to siphon off messages” that the security team believed might be a hacker, cited three former Yahoo employees and someone apprised of the events (though I think the original may have relied on just two former Yahoo employees).

NYT had a story, by legal reporter Charlie Savage and cyber reporter Nicole Perloth and relying on “two government officials” and another without much description, that seems to have gotten the legal mechanism correct — an individual FISA order — but introduced the claim that the scan used Yahoo’s existing kiddie porn filter and that “the technical burden on the company appears to have been significantly lighter” than the request earlier this year to Apple to unlock Syed Rezwan Farook’s iPhone.

A second Reuters story, by policy reporter Dustin Volz and spook writer Mark Hosenball, initially reported that the scan occurred under Section 702 authority, though has since corrected that to match the NYT report. It initially relied on government sources and reported that the “intelligence committees of both houses of Congress … are now investigating the exact nature of the Yahoo order,” which explains a bit about sourcing.

Motherboard’s tech writer Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchieri later had a story, relying on ex-Yahoo employees, largely confirming Reuters’ original report and refuting the NYT’s technical description. It described the tool as “more like a ‘rootkit,’ a powerful type of malware that lives deep inside an infected system and gives hackers essentially unfettered access.”

A followup story by Menn cites intelligence officials reiterating the claim made to NYT — that this was a simple tweak of the spam filter. But then it goes on to explain why that story is bullshit.

Intelligence officials told Reuters that all Yahoo had to do was modify existing systems for stopping child pornography from being sent through its email or filtering spam messages.

But the pornography filters are aimed only at video and still images and cannot search text, as the Yahoo program did. The spam filters, meanwhile, are viewable by many employees who curate them, and there is no confusion about where they sit in the software stack and how they operate.

The court-ordered search Yahoo conducted, on the other hand, was done by a module attached to the Linux kernel – in other words, it was deeply buried near the core of the email server operating system, far below where mail sorting was handled, according to three former Yahoo employees.

They said that made it hard to detect and also made it hard to figure out what the program was doing.

Note, to some degree, the rootkit story must be true, because otherwise the security team would not have responded as it did. As Reuters’ sources suggest, the way this got implemented is what made it suspicious to the security team. But that doesn’t rule out an earlier part of the scan involving the kiddie porn filter.

To sum up: ex-Yahoo employees want this story to be about the technical recklessness of the request and Yahoo’s bureaucratic implementation of it. Government lawyers and spooks are happy to explain this was a traditional FISA order, but want to downplay the intrusiveness and recklessness of this by claiming it just involved adapting an existing scan. And intelligence committee members mistakenly believed this scan happened under Section 702, and wanted to make it a 702 renewal fight issue, but since appear to have learned differently.

The ungagged position of the ex-Yahoo employees

Three comments about the ex-Yahoo sources here. First, the stories that rely on ex-Yahoo employees both include a clear “decline to comment” from Alex Stamos, the Yahoo CISO who quit and moved to Facebook in response to this event. If that decline to comment is to be believed, these are other former Yahoo security employees who have also since left the company.

Another thing to remember is that ex-Yahoo sources were already chatting to the press, though about the 2014 breach that exposed upwards of 500 million Yahoo users. This Business Insider piece has a former Yahoo person explaining that the architecture of Yahoo’s systems is such that billions of people were likely exposed in the hack.

“I believe it to be bigger than what’s being reported,” the executive, who no longer works for the company but claims to be in frequent contact with employees still there, including those investigating the breach, told Business Insider. “How they came up with 500 is a mystery.”

[snip]

According to this executive, all of Yahoo’s products use one main user database, or UDB, to authenticate users. So people who log into products such as Yahoo Mail, Finance, or Sports all enter their usernames and passwords, which then goes to this one central place to ensure they are legitimate, allowing them access.

That database is huge, the executive said. At the time of the hack in 2014, inside were credentials for roughly 700 million to 1 billion active users accessing Yahoo products every month, along with many other inactive accounts that hadn’t been deleted.

[snip]

“That is what got compromised,” the executive said. “The core crown jewels of Yahoo customer credentials.”

I can understand why Yahoo security people who lost battles to improve Yahoo’s security but are now at risk of being scapegoated for a costly problem for Yahoo would want to make it clear that they fought the good fight only to be overruled by management. The FISA scan provides a really succinct example of how Yahoo didn’t involve its security team in questions central to the company’s security.

One more thing. While Stamos and maybe a few others at Yahoo presumably had (and still have) clearance tied to discussing cybersecurity with the government, because none of them were involved in the response to this FISA order, none of them were read into it. They probably had and have non-disclosure agreements tied to Yahoo (indeed, I believe one of these stories originally referenced an NDA but has since taken the reference out). But because Yahoo didn’t involve the security team in discussions about how to respond to the FISA request, none of them would be under a governmental obligation, tied to FISA orders, to keep this story secret. So they could be sued but not jailed for telling this story.

It wouldn’t be the first time that the government’s narrow hold on some issue made it easier for people to independently discover something, as Thomas Tamm and Mark Klein did with Stellar Wind and the whole world did with StuxNet.

Stories still conflict about what happened after the scan was found

Which brings me to one of the most interesting conflicts among the stories now. I think we can assume the scan involved a single FISA order served only on Yahoo that Yahoo, for whatever reason, implemented in really reckless fashion.

But the stories still conflict on what happened after the security team found the scan.

Yahoo’s non-denial denial (issued after an initial, different response to the original Reuters story) emphasizes that no such scan currently remains in place.

We narrowly interpret every government request for user data to minimize disclosure. The mail scanning described in the article does not exist on our systems.

That could mean the scan was ended when the security team found it, but it could also mean Yahoo hurriedly removed it after Reuters first contacted it so it could claim it was no longer in place.

The original Reuters story doesn’t say what happened, aside from describing Stamos’ resignation. NYT’s spook and lawyer sources said, “The collection is no longer taking place.” The updated congressionally-sourced Reuters story says the scan was dismantled and not replaced before Stamos left.

Former Yahoo employees told Reuters that security staff disabled the scan program after they discovered it, and that it had not been reinstalled before Alex Stamos, the company’s former top security officer, left the company for Facebook last year.

The Motherboard story is the most interesting. It suggests that the security team found the scan, started a high severity response ticket on it, Stamos spoke with top management, and then that response ticket disappeared.

After the Yahoo security team discovered the spy tool and opened a high severity security issues within an internal tracking system, according to the source, the warning moved up the ranks. But when the head of security at the time, Alex Stamos, found out it was installed on purpose, he spoke with management; afterward, “somehow they covered it up and closed the issue fast enough that most of the [security] team didn’t find out,“ the source said.

The description of the disappearing ticket could mean a lot of things. But it doesn’t explain whether the scan itself (which the security team could presumably have found again if it worked in the same fashion) continued to operate.

Reuters’ latest story suggests the scan remained after the security team learned that Marissa Mayer had approved of it.

In the case of Yahoo, company security staff discovered a software program that was scanning email but ended an investigation when they found it had been approved by Chief Executive Officer Marissa Mayer, the sources said.

This seems to be consistent with Motherboard’s story about the disappearing ticket — that is, that the investigation ended because the ticket got pulled — but doesn’t describe how the scan continued to operate without more security people becoming aware of it.

But the implication of these varying stories is that the scan may have been operating (or restarted, after Stamos left), in a way that made Yahoo vulnerable to hackers, up until the time Reuters first approached Yahoo about the story. Even NYT’s best-spin sources don’t say when the scan was removed, which means it may have been providing hackers a back door into Yahoo for a year after the security team first balked at it.

Which might explain why this story is coming out now. And why ODNI is letting Yahoo hang on this rather than providing some clarifying details.

And what if the target of this scan is IRGC

As you know, I wildarse guessed that the target of this scan is likely to be Iran’s Revolutionary Guard. I said that because we know IRGC at least used to use Yahoo in 2011, we know the FISC long ago approved treating “Iran” as a terrorist organization, and because there are few other entities that could be considered “state-sponsored terrorist groups.” I think NYT’s best-spin sources might have used that term in hopes everyone would yell Terror!! and be okay with the government scanning all of Yahoo’s users’ emails.

But the apparent terms of this scan conflict with the already sketchy things the IC has told the European Union about our spying on tech companies. So the EU is surely asking for clarifying details to find out whether this scan — and any others like it that the FISC has authorized — comply with the terms of the Privacy Shield governing US tech company data sharing.

And while telling the NYT “state-sponsored terrorist group” might impress the home crowd, it might be less useful overseas. That’s because Europe doesn’t treat the best basis for the claim that IRGC is a terrorist group — its support of Hezbollah — the the same light we do. The EU named Hezbollah’s military wing a terrorist group in 2013, but as recently as this year, the EU was refusing to do so for the political organization as a whole.

That is, if my wildarseguess is correct, it would mean not only that an intelligence request for a back door exposed a billion users to hackers, but also that it did so to pursue an entity that not even all our allies agree is a top counterterrorism (as distinct from foreign intelligence) target.

Thus, it would get to the core of the problem with the claim that global tech companies can install back doors with no global ramifications, because there is no universally accepted definition of what a terrorist is.

Which, again, may be why ODNI has remained so silent.