FBI Rewrote the Backdoor Search Query Requirement

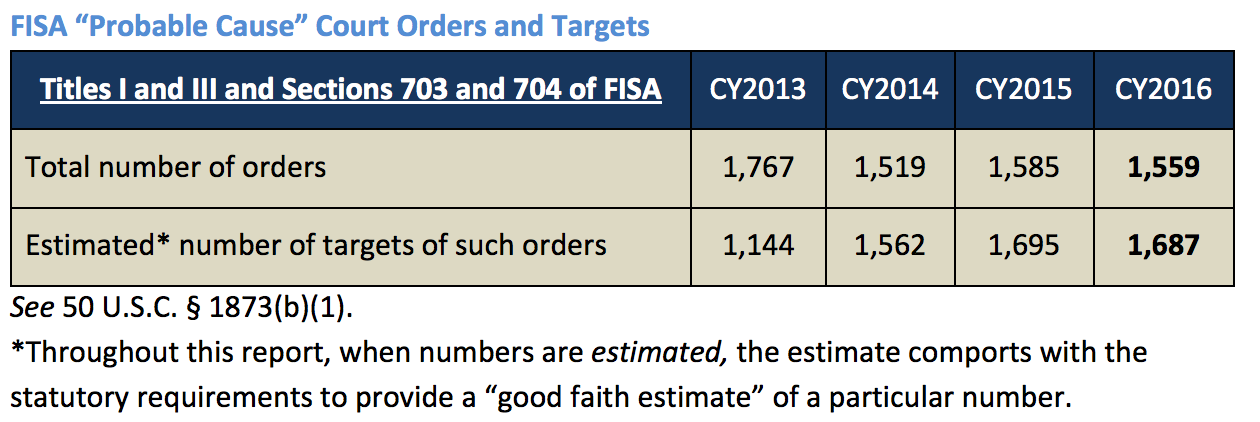

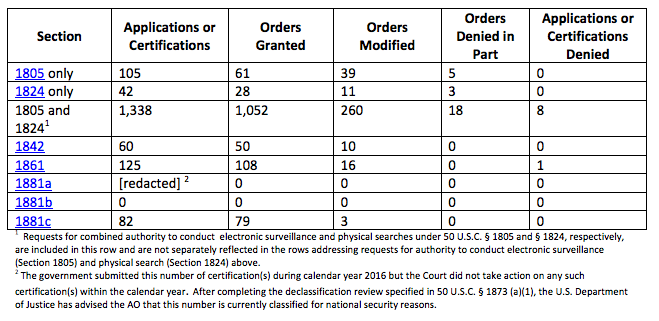

In her opinion approving the April 26 certifications (which may be one of the most unimpressive FISC opinions I’ve read), Rosemary Collyer borrowed heavily on the 2015 authorization in finding this year’s constitutional. As such she refers to Thomas Hogan’s imposition of a reporting requirement for any back door searches “in which FBI personnel receive and review Section 702-acquired information that the FBI identifies as concerning a United States person in response to a query that is not designed to find and extract foreign intelligence information.”

She then describes the one incident reported this year: basically an Agent seeing an email of someone referring to violence toward children. The Agent searched on the person who allegedly committed the violence and the names of the children, only to find the same email again. The Agent reported the suspected child abuse to the local child protective services.

But, she reveals, no one reported this until DOJ’s National Security Division asked about such reporting during their review.

The Court notes, however, that the FBI did not identify those queries as responsive to the Court’s reporting requirement until NSD asked whether any such queries had been made in the course of gathering information about the Section I.F dissemination. Notice at 2. The Court is carrying forward this reporting requirement and expects the government to take further steps to ensure compliance with it.

There are several reasons this is troublesome.

First, the incident would have gone unreported unless someone felt obliged to be honest when asked specifically about it (ODNI/DOJ don’t do reviews in all field offices, so not everyone will get asked).

Moreover, the incident got reported not because it was “receive[d] and reviewe[d],” but because it was disseminated. So there may be a great deal of back door searches that get received and reviewed but because they don’t constitute evidence of a crime, aren’t disseminated, with the consequent paper trail.

Finally, this means certain kinds of criminal searches won’t be reported: those where FBI gets a criminal tip, then looks on their 702 data, only to find something they might use to coerce informants. Information used to coerce informants would suddenly become foreign intelligence information, so no longer subject to the reporting requirement.

To meet the actual requirement from FISC — rather than the one they’re willing to comply with — FBI needs to dramatically restructure the compliance to this reporting requirement, to measure when a search is done for criminal purposes, and then — as soon as an agent conducts that review — gets noticed to the FISC.

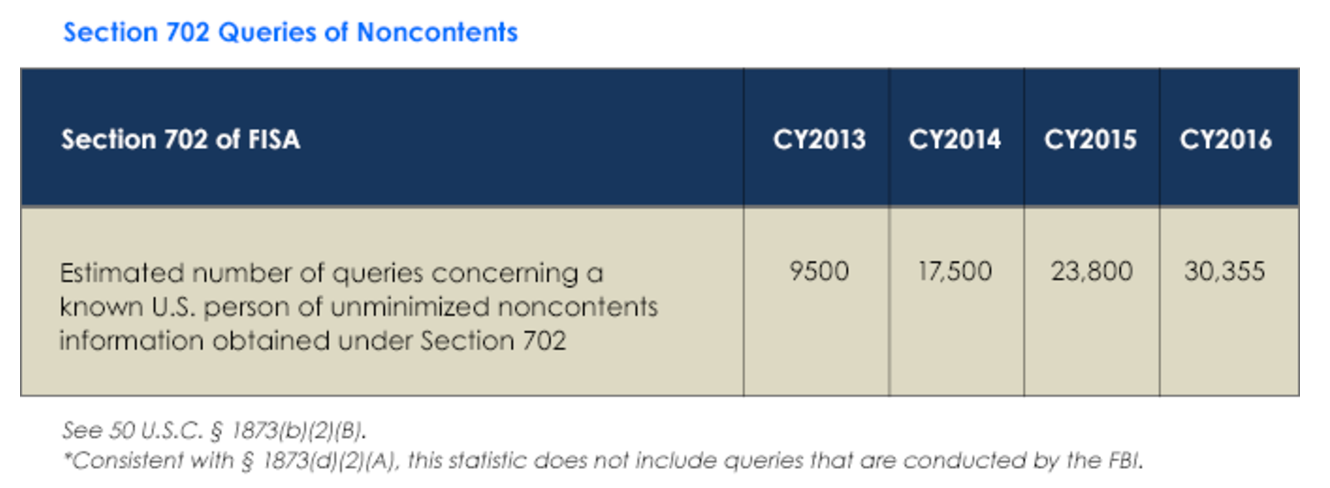

Of course, that would require precisely the kind of tracking the FBI has refused to do. Their arbitrary rewriting of this requirement demonstrates why.

Update: In application for certificates submitted on September 26, 2016, DOJ said this about its back door searches:

In a latter filed on December 4, 2015, the government noted that there is no automated way for the FBI to track whether a query is run solely for a foreign intelligence purpose, to extract evidence of a crime, or both. However, the December 4, 2015 letter detailed the processes the FBI put in place to attempt to identify those queries that are run in FBI systems containing raw 702-acquired information after December 4, 2015, that are designed to extract evidence of a crime. In addition, the December 4, 2015 letter explained that FBI had issued guidance to its personnel about this reporting requirement and the process to enable FBI to centrally track such scenarios and report any such queries to NSD that would fall under the reporting requirement described above. Additionally, NSD conducts minimization reviews in multiple FBI field offices each year. As part of these minimization reviews, NSD and FBI National Security Law Branch have emphasized the above requirements and processes during field office training. Further, during the minimization reviews, NSD audits a sample of queries performed by FBI personnel in the databases storing raw FISA-acquired information, including raw section 702-acquired information. Since December 2015, NSD has reviewed these queries to determine if any such queries were conducted solely for the purpose of retaining evidence of a crime. If such a query was conducted, NSD would seek additional information from the relevant FBI personnel as to whether FBI personnel received and reviewed section 702-acquired information of or concerning a U.S. person in response to such a query. Since the above processes were put in place in December 2015, FBI and NSD have not identified any instance in which FBI personnel have received and reviewed section 702-acquired information of or concerning a United States person in response to a query that is not designed to find and extract foreign intelligence information.

There are several key details here.

First, DOJ reported no queries on September 26, which means the query must have happened after that (though it’s not clear whether Collyer’s opinion would reflect the most recent reporting).

It’s also clear DOJ will only find these in spot checks. As DOJ makes clear here (and as was misrepresented at a recent hearing), NSD and ODNI don’t actually visit every FBI office (though I’m sure they hit SDNY, EDNY, DC, EDVA, MD, and NDCA routinely, which are the biggest national security offices). That means there’s not going to be a chance to find many possible queries.

There’s also some fuzzy language here. I’m particularly intrigued by this double usage of “FBI personnel,” as if someone from outside of FBI does review this, perhaps on an analytical contract.

If such a query was conducted, NSD would seek additional information from the relevant FBI personnel as to whether FBI personnel received and reviewed section 702-acquired information of or concerning a U.S. person in response to such a query.

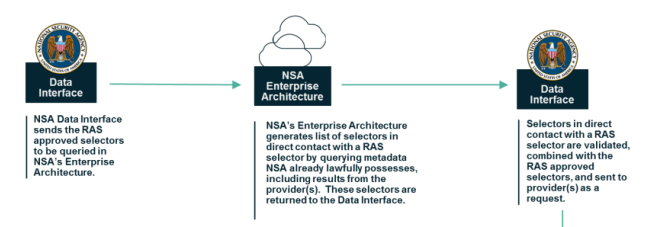

Or perhaps FBI calls up NSA and asks them to access the same content?

Finally, it’s clear the definition FBI is using, with respect to “foreign intelligence, crime, or both” permits generalized queries (in part to see if there’s intelligence to use to coerce someone to be an informant) that could serve either purpose. Such an approach cannot measure how much more often someone more likely to talk with a 702 target — like Muslims or Chinese-Americans — get pursued for crimes after a longer assessment decides against using the person as an informant.

Which is another way of saying that this metric is not measuring what Judge Hogan wanted it to measure.