NSA’s Unsatisfying Response to Rosemary Collyer’s “Lack of Candor” Accusations

In yesterday’s 702 hearing, Chuck Grassley asked NSA and FBI to explain why Rosemary Collyer (who I believe is the worst presiding FISA judge of the modern tennis era) accused them of a lack of candor.

FBI’s Carl Ghattas dodged one such accusation, but basically admitted what I laid out here with regards to the other — that FBI really wasn’t set up to fulfill Thomas Hogans 2015 order to report on any queries that return criminal information. Ghattas promised FBI would fix that; I’m skeptical the current structure of FBI audits will facilitate that happening but I’m happy to be proven wrong.

I want to look more closely at how Paul Morris, NSA’s Deputy General Counsel for Operations, explained the 10-month delay in informing the FISC about the NSA’s prohibited searches of upstream content.

We had initially identified that we had made some errors of US person queries against our upstream collection. So since 2011, our minimization procedures had prohibited outright any US person queries running against upstream 702 collection, largely because of abouts communications. We had reported the initial query errors — I believe it was in 2015 when we made the initial report, but our Office of Inspector General as well as our compliance group had separate reviews ongoing to try to determine the scope and scale of the problem. So during the course of filing the renewal for the 702 certifications that were pending, the court held a hearing in early October 2016 when it asked about various compliance matters to include the improper queries and we reported on the status of those investigations as we knew them to be at that time. On about two, I think, two or three weeks later, the Office of Inspector General completed its follow-up review of the US person query and discovered that the scope of the problem was larger than we’d originally reported. Soon as we identified that the problem was larger than we thought it was, we notified the Justice Department and the ODNI, in turn the court was notified and the court held a hearing on October 26 to go into further detail about the problem and it ultimately led to a couple of extensions of the certifications and ultimately our decision to terminate abouts collection in order to remedy the compliance problem. So my sense is that the institutional lack of candor that the court was referring to was really frustration that when we had the hearing on October 6 [sic] we did not know the full scope and scale of the problem until later which was reported roughly, again, October 24, which led to a hearing on October 26, which was the day before the court was supposed to rule on extending the certification.

As a reminder, this problem actually extends back to at least 2013. As I’ll eventually show, NSA obtained back door search authority in 2011 after a series of unauthorized back door searches, meaning they were just approving something that was already being done, just as this year’s opinion just approved searches that were going on in uncontrolled fashion.

Furthermore, while NSA surely informed the FISC of some of these problems along the way (otherwise I wouldn’t have known about them when I called them out last August), it did not deal with the ongoing problems in its application, which would have flagged an ongoing compliance problem of the magnitude shown even by the 2016 IG Report.

Morris’ claim that NSA’s IG reached some kind of conclusory decision between the first hearing on October 4 and the notice of the further problems on October 24 is dubious, given that the NSA said that follow-up study was still ongoing in a January 3 filing.

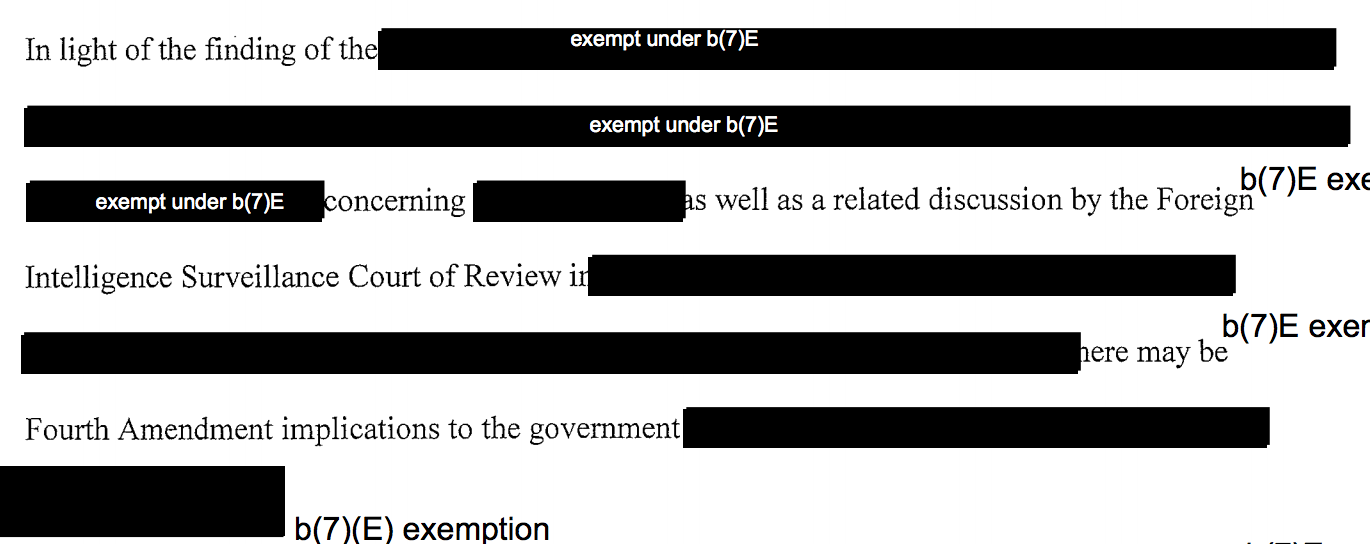

In anticipation of the January 31 deadline, the government updated the Court on these querying issues in the January 3, 2017 Notice. That Notice indicated that the IG’s follow-on study (covering the first quarter of 2016) was still ongoing.

As Collyer noted, at that point the NSA was still identifying all the systems implicated, notably finding queries that elude NSA’s query audit system.

It also appeared that NSA had not yet fully assessed the scope of the problem: the IG and OCO reviews “did not include systems through which queries are conducted of upstream data but that do not interface with NSA’s query audit system.” Id. at 3 n.6. Although NSD and ODNI undertook to work with NSA to identify other tools and systems in which NSA analysts were able to query upstream data, id., and the government proposed training and technical measures, it was clear to the Court that the issue was not yet fully scoped out.

Also at this point, NSA was “disclosing” the root cause of the problem as the same one identified back in 2013 and 2014, when NSA dismissed the possibility of a technical fix to the opt-out problem.

The January 3, 2017 Notice stated that “human error was the primary factor” in these incidents, but also suggested that system design issues contributed. For example, some systems that are used to query multiple datasets simultaneously required analysts to “opt-out” of querying Section 702 upstream Internet data rather than requiring an affirmative “opt-in,” which, in the Court’s view, would have been more conducive to compliance. See January 3, 2017 Notice at 5-6.

Ultimately, this chronology — and Morris’ unsatisfactory explanation for it — ought to raise real questions about what the bar is for the NSA declaring systems to be totally out of control, requiring immediate corrective action. I believe the NSA had reached that point on upstream searches at least by 2015. But it kept doing prohibited back door searches (which Collyer, because she’s the worst presiding FISC judge in recent memory, retroactively blessed) on abouts collection for another two years before the front end of about collection was shut down.

So perhaps the problem isn’t a lack of candor? Perhaps the problem is NSA can continue spying on entirely domestic communications for two years after identifying the problem before any fix is put in place?

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)