On 702, NSA Wants to Assure You You’re Not a Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target Target

NSA just released a touchy-feely Q&A, complete with a touchy-feely image of the NSA, explaining “the Impact of Section 702 on the Typical American.”

I shall now shred it.

First note that this document deals with 702? It should be dealing with Title VII, because the entire thing gets reauthorized by 702 reauthorization. That means Sections 704 and 705(b), which are used to target Americans, will be reauthorized. And they have had egregious problems in recent years (even if the problems only affect some subset of around 300 Americans). Sure, Paul Manafort and Carter Page are not your “typical” Americans, but abuses against them would be problematic for reasons that could affect Americans (not least that they could fuck up the Mueller probe if FISA disclosure for defendants weren’t so broken).

The piece starts by talking about how the IC uses 702 to “hunt” for information on “adversaries,” which it suggests include terrorists and hackers.

The U.S. Intelligence Community relies on Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in the constant hunt for information about foreign adversaries determined to harm the nation or our allies. The National Security Agency (NSA), for example, uses this law to target terrorists and thwart their plans. In a time of increasing cyber threats, Section 702 also aids the Intelligence Community’s cybersecurity efforts.

Somehow, it neglects to mention the foreign government certificate — which can target people who aren’t “adversaries” at all, but instead foreign muckety mucks we want to know about — or the counterproliferation certificate — which can target businesses of all kinds that deal in dual use technologies. Not to mention the SysAdmins that it might target for all these purposes.

The piece then lays out in two paragraphs and six questions (I include just one below) the basic principles that 702 can only “target” foreigners overseas.

Under Section 702, the government cannot target a U.S. person anywhere in the world, or any person located in the United States.

Under Section 702, NSA can target foreigners reasonably believed to be located outside the United States only if it has a basis to believe it will acquire certain types of foreign intelligence information that have been authorized for collection.

[snip]

Q: Can I, as an American, be the target of Section 702 surveillance?

A: No. As an American citizen, you cannot be the target of surveillance under Section 702. Even if you were not an American, you could not be targeted under Section 702 if you were located in the United States.

Effectively, this passage might as well say, “target target target target target target target target target target

target target target target target target target target target,” which is how many times (19) the word is used in the touchy-feely piece. The word “incidental” appears just once, where it entertains what happens if one of “Mary’s” foreign relatives were in a terrorist organization.

Q: One of Mary’s foreign relatives in South America is a member of an international terrorist group. Could Mary’s conversations with that relative be collected under Section 702?

A: Yes, it’s possible, if the U.S. government is aware of the relative’s membership in a terrorist group and the relative is one of the 106,000 targets under Section 702. However, even if this scenario occurred, there would still be protections in place for Mary, a U.S. citizen, if her conversations with that target were incidentally intercepted. For example:

U.S. intelligence agencies’ court-approved minimization procedures are specifically designed to protect the privacy of U.S. persons by, among other things, limiting the circumstances in which NSA can include the identity of a U.S. person in an intelligence report. Moreover, even where those procedures allow the NSA to include the identity of a U.S. person in an intelligence report, NSA frequently substitutes the U.S. person identity with a generic phrase or term, such as “U.S. person 1” or “a named U.S. person.” NSA calls this “masking” the identity of the U.S. person.

There are also what’s known as “age-off requirements”: After a certain period of time, the IC must delete any unminimized Section 702 information, regardless of the nationality of the communicants.

I guess the NSA figured if they used “Fatima,” whose relatives were in Syria, this scenario would be too obvious?

Yet in this, the only discussion of “incidental” collection, the NSA doesn’t explain how it is used — for example to find informants (meaning Fatima might be coerced into informing on her mosque if she discussed her tax dodging with her cousin) or to find 2nd degree associates (meaning Fatima’s friend in the US, Mohammed, might get an FBI visit because Fatima’s cousin in Syria is in ISIS). It also doesn’t explain that the “age-off” is five years, if Fatima is lucky enough to avoid having the FBI deem her conversations with her cousin in Syria interesting. If not, the data will sit on an FBI server for 30 years, ready to provide an excuse to give Fatima extra attention next time some bigot gets worried because he sees her taking pictures at Disney World.

Curiously, while the NSA doesn’t address the disproportionate impact of 702 on Muslims, it does pretend to address the disproportionate impact on Asians or their family members — people like like Xiaoxiang Xi and Keith Gartenlaub.

Q: Could the government target my colleague, who is a citizen of an Asian country, as a pretext to collect my communications under Section 702?

A: No. That would be considered “reverse targeting” and is prohibited.

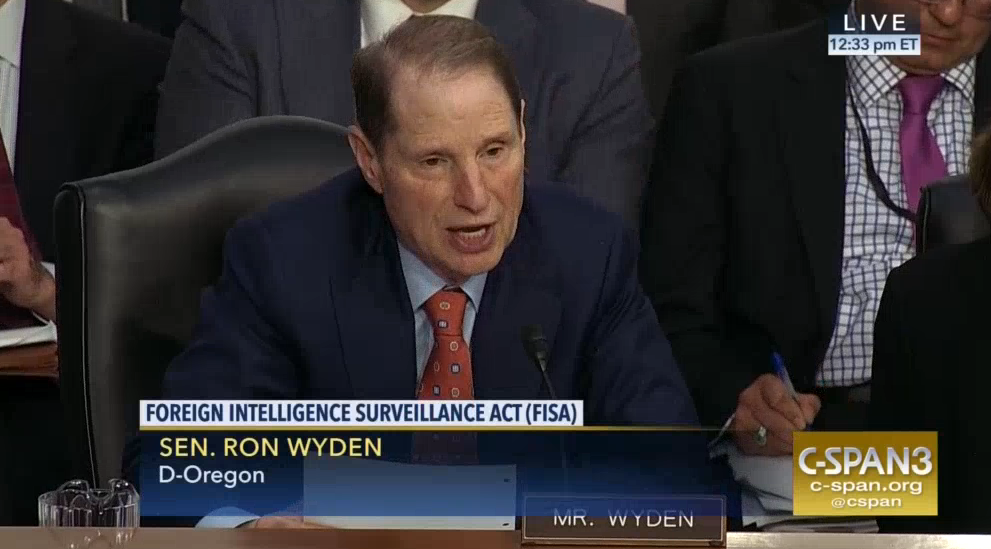

Thanks to Ron Wyden, we know how cynically misleading this answer is. He explained in the SSCI 702 reauthorization bill report that the government may,

conduct unlimited warrantless searches on Americans, disseminate the results of those searches, and use that information against those Americans, so long as it has any justification at all for targeting the foreigner.

Effectively, the government has morphed the “significant purpose” logic from the PATRIOT Act onto 702, meaning collecting foreign intelligence doesn’t have to be the sole purpose of targeting a foreigner; learning about what an American is doing, such as a scientist engaging in scientific discussion, can be one purpose of the targeting.

After dealing with unmasking, the NSA then performs the always cynical move of asking whether the NSA can query US person content.

Q: Can NSA use my information to query lawfully collected 702 data?

A: NSA can query already lawfully collected Section 702 information using a U.S. person’s name or identifier (such as an e-mail account or phone number) only if the query is reasonably designed to identify foreign intelligence information.

However, a U.S. person is still afforded protection. The justification for the query must be documented. The process for conducting a query is also subject to internal controls. Such queries are reviewed by the Department of Justice and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to ensure they meet the relevant legal requirements. Additionally, if the query was subsequently identified as being improper, it would be reported to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court and to Congress.

This passage is absolutely correct. But also absolutely beside the point, because NSA sends a significant chunk of its collection to the FBI where it can be searched to assess leads and search for evidence of crimes, and where queries get nowhere near the kind of oversight that NSA queries get.

Then the piece tries to explain the need for all the secrecy.

Q: Terrorists aim to hurt Americans and our allies, so why doesn’t the Intelligence Community share more Section 702 information about how the IC goes after them?

A: The Intelligence Community has dramatically enhanced transparency, especially regarding its implementation of Section 702. Thousands of pages of key documents have been officially released, and are available on IC on the Record. The public has more information than ever before on how the IC uses this critical foreign surveillance authority. That said, the IC must continue to protect classified information. This includes specifics on whether or not it has collected information about any particular individual.

If terrorists could find out that NSA had intercepted their communications, terrorists would likely change their communications methods to avoid further detection.

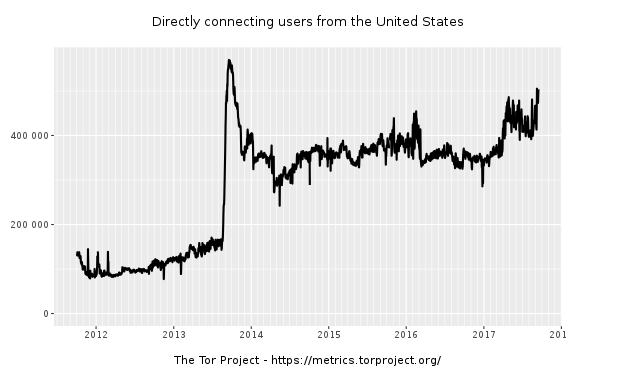

This is, partly, a straw man. People aren’t really asking to know NSA’s individual targets. They’re asking to know whether the government has back doored their iPhones via demands under FISA, or whether the NSA is collecting on the 430,000 Americans that use Tor every day, or if they’re also using this “foreign intelligence” collection program to hunt Americans buying drugs on Dark Markets or even BLM activists that our racist Attorney General has deemed a threat to national security. And in the name of keeping secrets from terrorists (who actually have the feedback mechanism of observing what gets their associates drone-killed to learn what gets collected), the government is refusing to admit that the answer to all those questions is yes: yes, the government has back doored our iPhones, yes, the government is spying on the 430,000 Americans that use Tor, and yes, for those who use Tor to buy drugs, they may even use 702 data to prosecute you.

Finally, the NSA pretends that everyone else in the world has a program just like this.

Q: Is the U.S. government the only one in the world with intercept programs like 702?

A: No. Many other countries have intelligence surveillance intercept programs, nearly all of which have far fewer privacy protections. Section 702 and its supporting policies and practices stand out in terms of strength of oversight, privacy protections, and public transparency.

It is true that other countries have “intercept programs,” but with the exception of China and Russia’s access to domestic Internet companies, no other country has a program “like 702” that, by virtue of the United States hosting the world’s most popular Internet companies, gives the US the luxury of spying on the rest of the world using a nice note to Google rather than having to hack users individually (or hack all users, as Russia did with Yahoo).

So, yes, the NSA has now offered a picture of itself, literally and metaphorically, that minimizes the scope, the thousands of spies it employs, and the reach, both domestic and global. But it’s a profoundly misleading picture.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)