Asha Rangappa Demands Progressive Left Drop Bad Faith Beliefs in Op-Ed Riddled with Errors Demonstrating [FBI’s] Bad Faith

It’s my fault, apparently, that surveillance booster Devin Nunes attacked the FBI this week as part of a ploy to help Donald Trump quash the investigation into Russian involvement in his election victory. That, at least, is the claim offered by the normally rigorous Asha Rangappa in a NYT op-ed.

It’s progressive left privacy defenders like me who are to blame for Nunes’ hoax, according to Rangappa, because — she claims — “the progressive narrative” assumes the people who participate in the FISA process, people like her and her former colleagues at the FBI and the FISA judges, operate in bad faith.

But those on the left denouncing its release should realize that it was progressive and privacy advocates over the past several decades who laid the groundwork for the Nunes memo — not Republicans. That’s because the progressive narrative has focused on an assumption of bad faith on the part of the people who participate in the FISA process, not the process itself.

And then, Ragappa proceeds to roll out a bad faith “narrative” chock full of egregious errors that might lead informed readers to suspect FBI Agents operate in bad faith, drawing conclusions without doing even the most basic investigation to test her pre-conceived narrative.

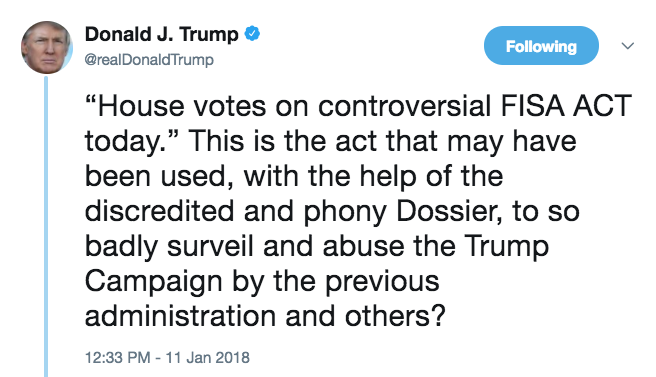

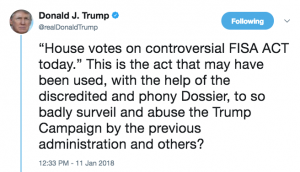

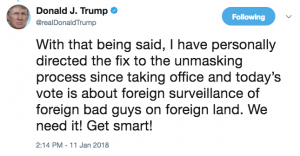

Rangappa betrays from the very start that she doesn’t know the least bit about what she’s talking about. Throughout, for example, she assumes there’s a partisan split on surveillance skepticism: the progressive left fighting excessive surveillance, and a monolithic Republican party that, up until Devin Nunes’ stunt, “has never meaningfully objected” to FISA until now. As others noted to Rangappa on Twitter, the authoritarian right has objected to FISA from the start, even in the period Rangappa used what she claims was a well-ordered FISA process. That’s when Republican lawyer David Addington was boasting about using terrorist attacks as an excuse to end or bypass the regime. “We’re one bomb away from getting rid of that obnoxious [FISA] court.”

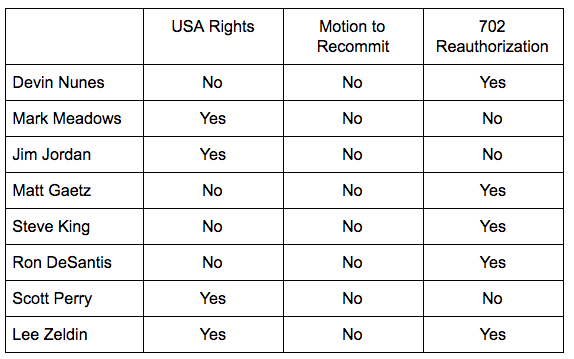

I’m more peeved, however, that Rangappa is utterly unaware that for over a decade, the libertarian right and the progressive left she demonizes have worked together to try to rein in the most dangerous kinds of surveillance. There’s even a Congressional caucus, the Fourth Amendment Caucus, where Republicans like Ted Poe, Justin Amash, and Tom Massie work with Rangappa’s loathed progressive left on reform. Amash, Mike Lee, and Rand Paul, among others, even have their name on legislative attempts to reform surveillance, partnering up with progressives like Zoe Lofgren, John Conyers, Patrick Leahy, and Ron Wyden. This has become an institutionalized coalition that someone with the most basic investigative skills ought to be able to discover.

Since Rangappa has not discovered that coalition, however, it is perhaps unsurprising she has absolutely no clue what the coalition has been doing.

In criticizing the FISA process, the left has not focused so much on fixing procedural loopholes that officials in the executive branch might exploit to maximize their legal authority. Progressives are not asking courts to raise the probable cause standard, or petitioning Congress to add more reporting requirements for the F.B.I.

Again, there are easily discoverable bills and even some laws that show the fruits of progressive left and libertarian right efforts to do just these things. In 2008, the Democrats mandated a multi-agency Inspector General on Addington’s attempt to blow up FISA, the Stellar Wind program. Progressive Pat Leahy has repeatedly mandated other Inspector General reports, which forced the disclosure of FBI’s abusive exigent letter program and that FBI flouted legal mandates regarding Section 215 for seven years (among other things). In 2011, Ron Wyden started his thus far unsuccessful attempt to require the government to disclose how many Americans are affected by Section 702. In 2013, progressive left and libertarian right Senators on the Senate Judiciary Committee tried to get the Intelligence Community Inspector General to review how the multiple parts of the government’s surveillance fit together, to no avail.

Rangappa’s apparent ignorance of this legislative history is all the more remarkable regarding the last several surveillance fights in Congress, USA Freedom Act and this year’s FISA Amendments Act reauthorization (the latter of which she has written repeatedly on). In both fights, the bipartisan privacy coalition fought for — but failed — to force the FBI to comply with the same kind of reporting requirements that the bill imposed on the NSA and CIA, the kind of reporting requirements Rangappa wishes the progressive left would demand. When a left-right coalition in the House Judiciary Committee tried again this year, the FBI stopped negotiating with HJC’s staffers, and instead negotiated exclusively with Devin Nunes and staffers from HPSCI.

With USAF, however, the privacy coalition did succeed in a few reforms (including those reporting requirements for NSA and CIA). Significantly, USAF included language requiring the FISA Court to either include an amicus for issues that present “a novel or significant interpretation of the law,” or explain why it did not. That’s a provision that attempts to fix the “procedural loophole” of having no adversary in the secret court, though it’s a provision of law the current presiding FISC judge, Rosemary Collyer, blew off in last year’s 702 reauthorization. (Note, as I’ve said repeatedly, I don’t think Collyer’s scofflaw behavior is representative of what FISC judges normally do, and so would not argue her disdain for the law feeds a “progressive narrative” that all people involved in the FISA process operated in bad faith.)

Another thing the progressive left and libertarian right won in USAF is new reporting requirements on FISA-related approvals for FISC, to parallel those DOJ must provide. Which brings me to Rangappa’s most hilarious error in an error-ridden piece (it’s an error made by multiple civil libertarians earlier in the week, which I corrected on Twitter, but Rangappa appears to mute me so wouldn’t have seen it).

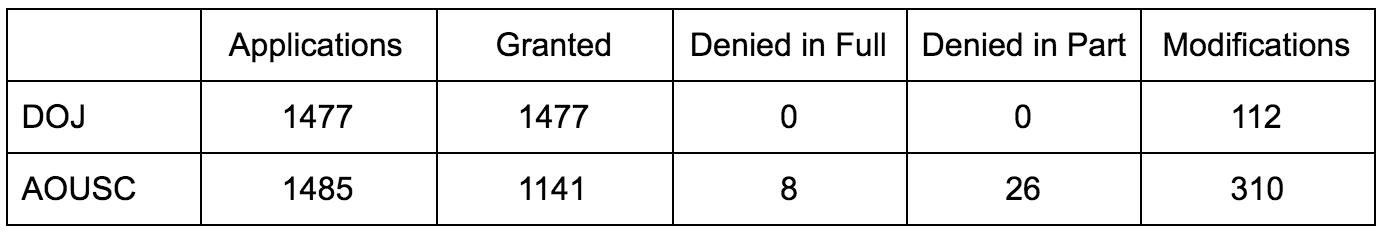

To defend her claim that the FISC judge who approved the surveillance of Carter Page was operating, if anything, with more rigor than in past years, Rangappa points to EPIC’s tracker of FISA approvals and declares that the 2016 court rejected the highest number of applications in history.

We don’t know whether the memo’s allegations of abuse can be verified. It’s worth noting, however, that Barack Obama’s final year in office saw the highest number of rejected and modified FISA applications in history. This suggests that FISA applications in 2016 received more scrutiny than ever before.

Here’s why this is a belly-laughing error. As noted, USAF required the FISA Court, for the first time, to release its own record of approving applications. It released a partial report (for the period following passage of USAF) covering 2015, and its first full report for 2016. The FISC uses a dramatically different (and more useful) counting method than DOJ, because it counts what happens to any application submitted in preliminary form, whereas DOJ only counts applications submitted in final form. Here’s how the numbers for 2016 compare.

Rangappa relies on EPIC’s count, which for 2016 not only includes an error in the granted number, but adopts the AOUSC counting method just for 2016, making the methodology of its report invalid (it does have a footnote that explains the new AOUSC numbers, but not why it chose to use that number rather than the DOJ one or at least show both).

Using the only valid methodology for comparison with past years, DOJ’s intentionally misleading number, FISC rejected zero applications, which is consistent or worse than other years.

It’s not the error that’s the most amusing part, though. It’s that, to make the FISC look good, she relies on data made available, in significant part, via the efforts of a bipartisan coalition that she claims consists exclusively of lefties doing nothing but demonizing the FISA process.

If anyone has permitted a pre-existing narrative to get in the way of understanding the reality of how FISA currently functions, it’s Rangappa, not her invented progressive left.

Let me be clear. In spite of Rangappa’s invocation (both in the body of her piece and in her biography) of her membership in the FBI tribe, I don’t take her adherence to her chosen narrative in defiance of facts that she made little effort to actually learn to be representative of all FBI Agents (which is why I bracketed FBI in my title). That would be unfair to a lot of really hard-working Agents. But I can think of a goodly number of cases, some quite important, where that has happened, where Agents chased a certain set of leads more vigorously because they fit their preconceptions about who might be a culprit.

That is precisely what has happened here. A culprit, Devin Nunes — the same guy who helped the FBI dodge reporting requirements Rangappa thinks the progressive left should but is not demanding — demonized the FISA process by obscuring what really happens. And rather than holding that culprit responsible, Rangappa has invented some other bad guy to blame. All while complaining that people ever criticize her FBI tribe.

![[Photo: National Security Agency, Ft. Meade, MD via Wikimedia]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/NationalSecurityAgency_HQ-FortMeadeMD_Wikimedia.jpg)