There’s a whiff of panic in DOJ’s response to ACLU’s latest brief in the common commercial services OLC memo, which was submitted last Thursday. They really don’t want to release this memo.

As you recall, this is a memo Ron Wyden has been hinting about forever, stating that it interprets the law other than most people understand it to be. After I wrote about it a bunch of times and pointed out it was apparently closely related to cybersecurity, ACLU finally showed some interest and FOIAed, then sued, for it. In March, DOJ made some silly (but typical) claims about it, including that ACLU had already tried but failed to get the memo as part of their suit for Stellar Wind documents (which got combined with EPIC’s suit for electronic surveillance documents). In response, Ron Wyden wrote a letter to Attorney General Loretta Lynch, noting a lie DOJ made in DOJ’s filings in the case, followed by an amicus brief asking the judge in the case to read the secret appendix to the letter he wrote to Lynch. In it, Wyden complained that DOJ wouldn’t let him read his secret declaration submitted in the case (making it clear they’re being kept secret for strategic reasons more than sources and methods), but asking that the court read his own appendix without saying what was in it.

Which brings us to last week’s response.

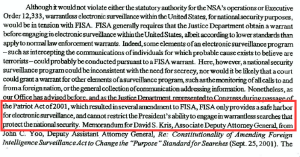

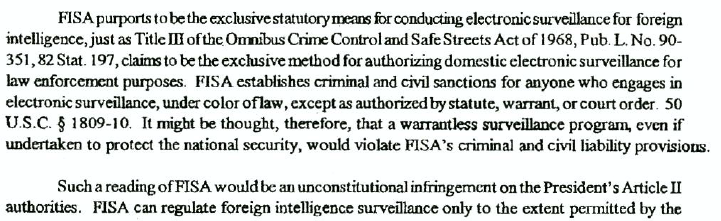

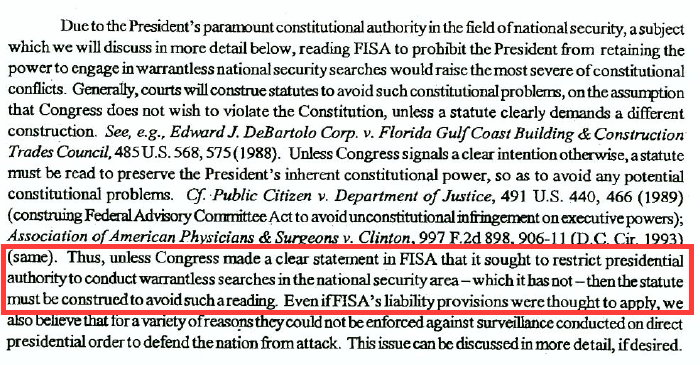

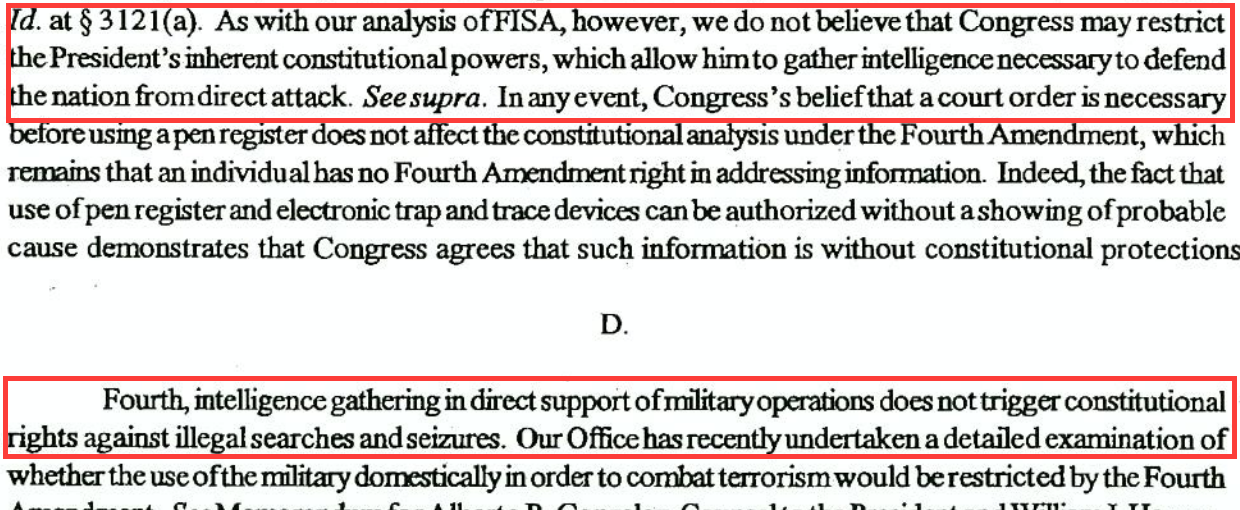

DOJ is relying on an opinion the 2nd circuit released last year in ACLU’s Awlaki drone memo case that found that if a significant delay passed between the time an opinion was issued and executive branch officials spoke publicly about it — as passed between the time someone wrote a memo for President Bush’s “close legal advisor” in 2002 about drone killings (potentially of American citizens) and the time Executive branch officials stopped hiding the fact they were planning on drone-killing an American citizen in 2010, then the government can still hide the memo.(I guess we’re not allowed to learn that Kamal Derwish was intentionally, not incidentally, drone-killed in 2002?)

This is, in my understanding, narrower protection for documents withheld under the b5 deliberative privilege exemption than exists in the DC Circuit, especially given that the 2nd circuit forced the government to turn over the Awlaki memos because they had been acknowledged.

In other words, they’re trying to use that 2nd circuit opinion to avoid releasing this memo.

To do that they’re making two key arguments that, in their effort to keep the memo secret, end up revealing a fair amount they’re trying to keep secret. First, they’re arguing (as they did earlier) that the ACLU has already had a shot at getting this memo (in an earlier lawsuit for memos relating to Stellar Wind) and lost.

There’s just one problem with that. As I noted earlier, the ACLU’s suit got joined with EPIC’s, but they asked for different things. ACLU asked for Stellar Wind documents, whereas EPIC asked more broadly for electronic surveillance ones. So when the ACLU argued for it, they were assuming it was Stellar Wind, not something that now appears to (also) relate to cybersecurity.

Indeed, the government suggests the ACLU shouldn’t assume this is a “Terrorist Surveillance Program” document.

7 Plaintiffs conclude that the OLC memorandum at issue here must relate to the Terrorist Surveillance Program and the reauthorization of that program because the attorney who authored the memorandum also authored memoranda on the Terrorist Surveillance Program. Pls.’ Opp. at 10. The fact that two OLC memoranda share an author of course establishes nothing about the documents’ contents, nature, purpose, or effect.

Suggesting (though not stating) the memo is not about TSP is not the same as saying it is not about Stellar Wind or the larger dragnets Bush had going on. But it should mean ACLU gets another shot at it, since they were looking only for SW documents the last time.

Which is interesting given the way DOJ argues, much more extensively, that this memo does not amount to working law. It starts by suggesting Wyden’s filing arguing a “key assertion” in the government’s briefs is wrong.

3 Senator Wyden asks the Court to review a classified attachment to a letter he sent Attorney General Loretta Lynch in support of his claim that a “key assertion” in the Government’s motion papers is “inaccurate.” Amicus Br. at 4. The Government will make the classified attachment available for the Court’s review ex parte and in camera. For the reasons explained in this memorandum, however, the Senator’s claim of inaccuracy is based not on any inaccurate or incomplete facts, but rather on a fundamental misunderstanding of the “working law” doctrine.

In doing so, it reveals (what we already expected but which Wyden, but apparently not DOJ, was discreet enough not to say publicly) that the government did whatever this John Yoo memo said government could do.

But, it argues (relying on both the DC and 2nd circuit opinions on this) that just because the government did the same thing a memo said would be legal (such as, say, drone-killing a US person with no due process), it doesn’t mean they relied on the memo’s advice when they took that action.

The mere fact that an agency “relies” on an OLC legal advice memorandum, by acting in a manner that is consistent with the advice, Pls.’ Opp. at 11, does not make it “working law.” OLC memoranda fundamentally lack the essential ingredient of “working law”: they do not establish agency policy. See New York Times, 806 F.3d at 687; Brennan Center, 697 F.3d at 203; EFF, 739 F.3d at 10. It is the agency, and not OLC (or any other legal adviser), that has the authority to establish agency policy. If OLC advises that a contemplated policy action is lawful, and the agency considers the opinion and elects to take the action, that does not mean that the advice becomes the policy of that agency. It remains legal advice. 5

5 Nor could the fact that any agency elects to engage in conduct consistent with what an OLC opinion has advised is lawful possibly constitute adoption of that legal advice, because taking such action does not show the requisite express adoption of both the reasoning and conclusion of OLC’s legal advice. See Brennan Center, 697 F.3d at 206; Wood, 432 F.3d at 84; La Raza, 411 F.3d at 358.

Effectively, DOJ is saying that John Yoo wrote another stupid memo just weeks before he left, the government took the action described in the stupid memo, but from that the courts should not assume that the government took Yoo’s advice, this time.

One reason they’re suggesting this isn’t TSP (which is not the same as saying it’s not Stellar Wind) is because it would mean the government did not (in 2005, when Bush admitted to a subset of things called TSP) confirm this action in the same way Obama officials danced around hailing that they had killed Anwar al-Awlaki, which led to us getting copies of the memos used to justify killing him.

In short, the government followed Yoo’s advice, just without admitting they were following his shitty logic again.