This is going to be a weedy post in which I look at a key detail revealed by 2010 NSA Inspector General reviews of the Section 215 phone dragnet. The document was liberated by Charlie Savage last year.

At issue is the government’s description, in the period after the Snowden leaks, of what kind of searches it did on the Section 215 phone dragnet. The searches the government did on Section 215 dragnet data are critical to understanding a number of things: the reasons the parallel Internet dragnet probably got shut down in 2011, the squeals from people like Marco Rubio about things the government lost in shutting down the dragnet, and the likely scope of collection under USA Freedom Act.

Throughout the discussion of the phone dragnet, the administration claimed it was used for “contact chaining” — that is, exclusively to show who was within 3 (and starting in 2014, 2) degrees of separation, by phone calls [or texts, see update] made, from a suspected terrorist associate.

Here’s how the administration’s white paper on the program described it in 2013.

This telephony metadata is important to the Government because, by analyzing it, the Government can determine whether known or suspected terrorist operatives have been in contact with other persons who may be engaged in terrorist activities, including persons and activities within the United States. The program is carefully limited to this purpose: it is not lawful for anyone to query the bulk telephony metadata for any purpose other than counterterrorism, and Court-imposed rules strictly limit all such queries.

Though some claims to Congress and the press were even more definitive that this was just about contact chaining.

The documents on the 2009 violations released under FOIA made it clear that, historically at least, querying wasn’t limited to contact chaining. Almost every reference in these documents to the scope of the program includes a redaction after “contact chaining” in the description of the allowable queries. Here’s one of many from the government’s first response to Reggie Walton’s questions about the program.

The redaction is probably something like “pattern analysis.”

Because the NSA was basically treating all Section 215 data according to the rules governing EO 12333 in 2009 (indeed, at the beginning of this period, analysts couldn’t distinguish the source of the two authorizations), it subjected the data to a number of processes that did not fit under the authorization in the FISC orders — things like counts of all contacts and automatic chaining on identifiers believed to be the same user as one deemed to have met the Reasonable Articulable Standard. The End to End report finished in summer 2009 described one after another of these processes being shut down (though making it clear it wanted to resume them once it obtained FISC authorization). But even in these discussions, that redaction after “contact chaining” remained.

Even in spite of this persistent redaction, the public claims this was about contact chaining gave the impression that the pattern analysis not specifically authorized by the dragnet orders also got shut down.

The IG Reports that Savage liberated gives a better sense of precisely what the NSA was doing after it cleared up all its violations in 2009.

The Reports were ordered up by the FISC and covered an entire year of production (there was a counterpart of the Internet dragnet side, which was largely useless since so much of that dragnet got shut down around October 30, 2009 and remained shut down during this review period).

The show several things:

- NSA continued to disseminate dragnet results informally, even after Reggie Walton had objected to such untrackable dissemination

- Data integrity techs could — and did on one occasion, which was the most significant violation in the period — access data directly and in doing so bypass minimization procedures imposed on analysts (this would be particularly useful in bypassing subject matter restrictions)

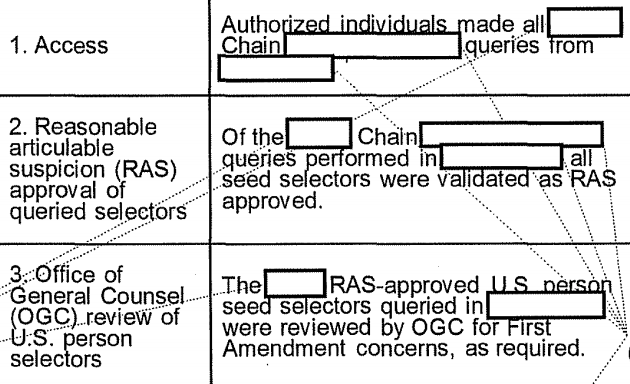

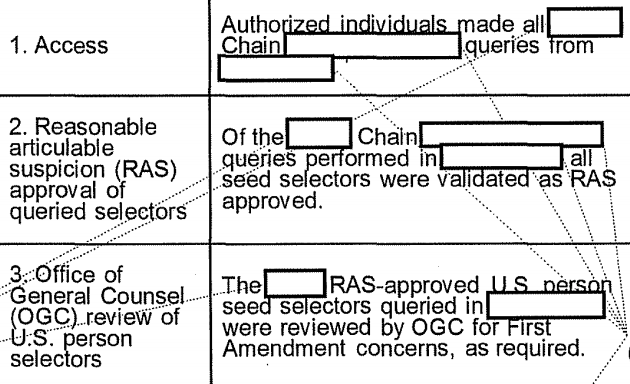

- Already by 2010, NSA did at least three different kinds of queries on the database data: in addition to contact chaining, “ident lookups,” and another query still considered Top Secret

It’s the last item of interest here.

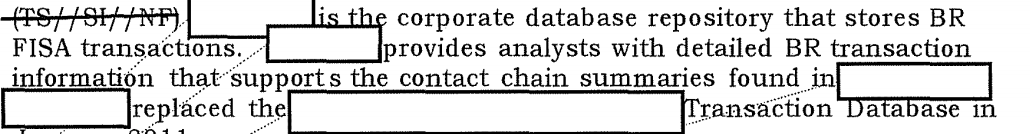

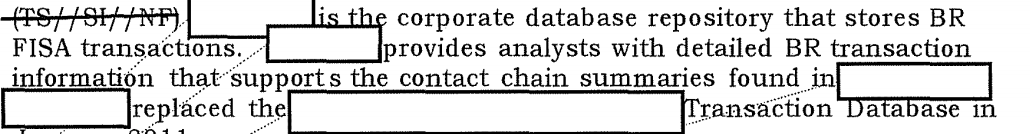

The first thing to understand about the phone dragnet data is it could be queried two places: the analyst front-end (the name of which is always redacted), and a “Transaction Database” that got replaced with something else in 2011. (336)

Basically, when the NSA did intake on data received from the telecoms, it would create a table of each and every record (which is I guess where the “transaction” name came from), while also making sure the telecoms didn’t send illegal data like credit card information.

Doing queries in the Transaction Database bypassed search restrictions. The March 2010 audit discovered a tech had done a query in the Transaction Database using a selector the RAS approval (meaning NSA had determined there was reasonable articulable suspicion that the selector had some tie to designated terrorist groups and/or Iran) of which had expired. The response to that violation, which NSA didn’t agree was a violation, was to move that tech function into a different department at NSA, away from the analyst function, which would do nothing to limit such restriction free queries, but would put a wall between analysts and techs, making it harder for analysts to ask techs to perform queries they would be unable to do.

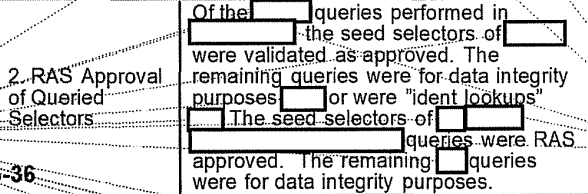

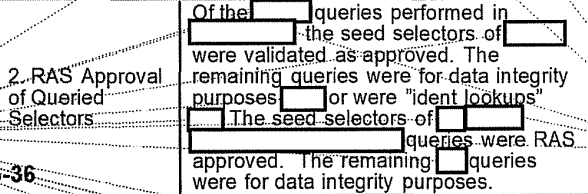

Because the direct queries done for data integrity purposes were not subject to auditing under the phone dragnet orders, the monthly reports distinguished between those and analyst queries, the latter of which were audited to be sure they were RAS approved. But as the April 2010 report and subsequent audits showed, analysts also would do an “ident lookup.” (83)

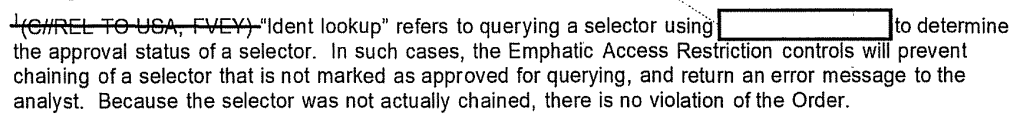

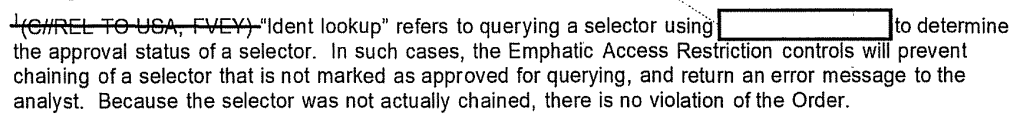

The report provided this classified/Five Eyes description of “ident lookups.”

The Emphatic Access Restriction was a tool implemented in 2009 to ensure that analysts only did queries on RAS-approved selectors. What this detail reveals is that, rather than consulting a running list somewhere to see whether a selector was RAS approved, analysts would instead try to query, and if the query failed, that’s how they would learn the selector was not RAS approved.

We can’t be sure, but that suggests RAS approval went beyond simple one-to-one matching of identifiers. It’s possible an ident lookup needed to query the database to see if the data showed a given selector (say, a SIM card) matched another selector (say, a phone number) which had been RAS approved. It might go even further, given that NSA had automatically done searches on “correlated” numbers (that is, on a second phone number deemed to belong to the same person as the approved primary number that had been RAS approved). At least, that’s something NSA had done until 2009 and said it wanted to resume.

In other words, the fact that an ident lookup query queried the data and not just a list of approved selectors suggests it did more than just cross-check the RAS approval list: at some level it must tested the multiple selectors associated with one user to see if the underlying selectors were, by dint of the user himself being approved, themselves approved.

Indent lookups appear fairly often in these IG reports. Less frequent is an entirely redacted kind of query such as described but redacted in the September 2010 report. (166)

The footnote description of that query is classified Top Secret NOFORN and entirely redacted.

I have no idea what that query would be, but it’s clear it is done on the analyst facing interface, and only on RAS approved selectors.

The timing of this third query is interesting. Such queries appear in the September and October 2010 audits. That was a period when, in the wake of the July 2010 John Bates approval to resume the Internet dragnet, they were aligning the two programs again (or perhaps even more closely than they had been in 2009). It also appears after a new selector tracking tool got introduced in June 2010. That said, I’m unaware of anything in the phone dragnet orders that would have expanded the kinds of queries permitted on the phone dragnet data.

We know they had used the phone dragnet until 2009 to track burner phones (that is, matching calling patterns of selectors unknown to have a connection to determine which was a user’s new phone). We know that in November 2012, FISC approved an automated query process, though NSA never managed to implement it technically before Obama decided to shut down the dragnet. We also know that in 2014 they started admitting they were also doing “connection” chaining (which may be burner phone matching or may be matching of selectors). All are changes that might relate to more extensive non-chain querying.

We also don’t know whether this kind of query persisted from 2010 until last year, when the dragnet got shut down. I think it possible that the reasons they shut down the Internet dragnet in 2011 may have implicated the phone dragnet.

The point, though, is that at least by 2010, NSA was doing non-chain queries of the entire dragnet dataset that it considered to be approved under the phone dragnet orders. That suggests by that point, NSA was using the bulk set as a set already (or, more accurately, again, after the 2009 violations) by September 2010.

Last March James Clapper explained the need to retain records for a period of time, he justified it by saying you needed the historical data to discern patterns.

Q: And just to be clear, with the private providers maintaining that data, do you feel you’ve lost an important tool?

Clapper: Not necessarily. It will depend though, for one, retention period. I think, given the attitude today of the providers, they will probably do all they can to minimize the retention period. Which of course, from our standpoint, lessens the utility of the data, because you do need some — and we can prove this statistically — you do need some historical data in order to, if you’re gonna discern a pattern. And again, 215 to me, is much like my fire insurance policy. You know, my house has never burned down but every year I buy fire insurance just in case.

This would be consistent with the efforts to use the bulk dataset to find burner identities, at a minimum. It would also be consistent with Marco Rubio et al’s squeals about needing the historical data. And it would be consistent with the invocation of the National Academy of Sciences report on bulk data (though not on the phone dragnet), which NSA’s General Counsel raised in a Lawfare post today.

In other words, contrary to public suggestions, it appears NSA was using the phone dragnet to conduct pattern analysis that required the bulk dataset. That’s not surprising, though it is something the NSA suggested they weren’t doing.

They surely are still doing that on the larger EO 12333 dataset, along with a lot more complex kinds of analysis. But it seems some, like Rubio, either think we need to return to such bulk pattern analysis, or has used the San Bernardino attack to call to resume more intrusive spying.

Update: One of the other things the IG Reports make clear is that NSA was (unsurprisingly) collecting records of non-simultaneous telephone transactions. That became an issue when, in 2011, NSA started to age-off 5 year old data, because they would have some communication chains that reflected communications that were more than 5 years old but which were obtained less than 5 years before.

My guess is this reflects texting chains that continued across days or weeks.