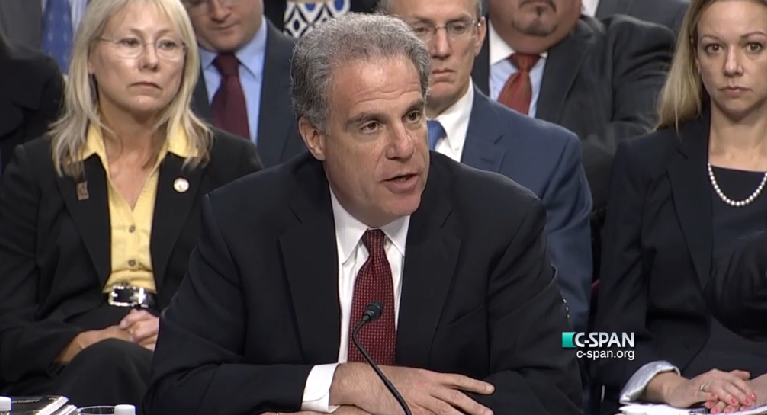

Last year, Bill Barr adopted the stance that Inspector General Michael Horowitz’s assessment of FISA — in the report on the Carter Page FISA applications — wasn’t strict enough, because it found no evidence that the errors in the applications arose from political bias. Last week, Bill Barr’s DOJ adopted the opposite stance, that DOJ IG was too critical of FISA, finding errors in the FBI process where there were none.

It did so in the second of two filings reviewing the errors that DOJ IG had found in 29 other FISA applications. When DOJ IG released an interim report (MAM) describing those errors in March, it appeared to suggest that the level of error in the Carter Page applications — at least with respect to the Woods Files — was actually lower than what DOJ IG had found in the 25 applications.

Now, DOJ appears to be trying to claim — without basis — that that’s not the case.

Ahead of the release of the actual filing, DOJ and FBI orchestrated a press release last week, announcing that they would tell the court none of the errors identified by DOJ IG invalidated the probable cause finding for the 29 files. Predictably, both the responsible press and the frothy right (in stories that misunderstood the findings of either DOJ IG report and at times made errors about the FISA process), concluded that this review shows that Page’s application was uniquely bad.

Only after the press had jumped on that conclusion did DOJ release the filing (here’s the earlier one and here’s AAG John Demers’ statement in conjunction with last week’s release).

The filing makes it clear that it is impossible to draw any comparison between these findings about the earlier Carter Page ones (or even to declare — as many in the press have — that this filing proves DOJ’s FISA problems aren’t as bad as DOJ IG suggested).

That’s true for three reasons:

- DOJ IG has not finished the kind of review on any of the 29 files it did for Page, and DOJ is not claiming it did either

- DOJ used a dramatically different methodology for this Woods review than DOJ IG did for the Page review

- DOJ effectively disagreed with DOJ IG’s findings for roughly 46% of the errors DOJ IG identified — and it’s not clear they explained to the FISA Court why they did so

Before I explain these, there’s a more important takeaway.

In giving itself a clean bill of health, DOJ judged that it doesn’t matter that a 2016 FISA application claimed that one of their sources accused a person of sympathizing with a particular terrorist organization when in fact the source said the person had become sympathetic to radical Muslim causes. For the purposes of FISA, this is a huge distinction, because a terrorist organization counts as a foreign power for the sake of FISA, but radical Muslim causes do not. It’s the difference between targeting someone as a suspected agent of a foreign power and targeting them for First Amendment protected activities. DOJ said this error didn’t matter because there was so much other derogatory information against the target; whether that’s true or not, it remains the case that DOJ’s self-congratulation nevertheless admits to a key First Amendment problem in one of the applications.

Woods violations are different from significant inaccuracies are different from material inaccuracies are different from probable cause

As I explained in this post, the IG Report on Carter Page found two types of problems: 17 “significant inaccuracies” that were mostly errors of omission (see PDF 12 and 14-15 for a list), and Woods file errors (PDF 460ff) for which an assertion made in the application did not have or match the back-up in the accuracy file that is supposed to prove it. The “significant inaccuracies” are the more serious of the two, but a number of those were overblown and in a few cases, dubious, in the DOJ IG Report.

Both of those categories are different from material misstatements, of which DOJ admitted to a number by the time they withdrew the probable cause claim from the third and fourth, but not the first two, Page applications. Before the conclusion of the DOJ IG Report they had told the court of the following material misstatements:

- July 12, 2018: Cover stories Papadopoulos gave to informants that FBI accurately assessed in real time as false, statements Bruce Ohr made that (in the slightly misrepresented form included in the DOJ IG Report) call into question Christopher Steele’s motives, admissions that Steele himself had spoken to the press

- October 25, 2019 and November 27, 2019: Details about the actions of Kevin Clinesmith — first not disclosing and then altering a document to hide Page’s relationship with the CIA that covered some but not all of his willful sharing of non-public information with known Russian intelligence officers

It’s not clear the government specified which aspects of the DOJ IG Report it submitted to Rosemary Collyer in December 2019 it deemed material, but she focused on:

- Statements made by Steele’s primary sub-source that undermined key claims about Page

- Page’s denials (some proven true, some of still undetermined veracity) of details in the Steele dossier

- Steele’s derogatory comments about Sergei Millian

On the scale of severity, the material misstatements are the ones that matter, because they’re the ones that will affect whether someone gets wiretapped or not. But the Woods file errors in the Carter Page report identified by DOJ IG describe just four (arguably, three) details even related to things ultimately deemed material which, in turn, led to the withdrawal of two of the applications. None directly described the core issues that led to the withdrawal of the two applications (though the Page denials in conjunction with the sub-source comments did).

Indeed, one key conclusion of this entire process — one that DOJ, DOJ IG, and FISC have all agreed with — is that the Woods files process is not very useful at finding the more important errors of omission of the kind that were the most serious problems in the Page application.

And that’s important because all three of these reports — the March DOJ IG MAM and the June and July responses to FISA — stem from, and only explicitly claim to address, Woods file errors. In its MAM, DOJ IG described what it called its “initial” review this way:

During this initial review, we have not made judgments about whether the errors or concerns we identified were material. Also, we do not speculate as to whether the potential errors would have influenced the decision to file the application or the FISC’s decision to approve the FISA application. In addition, our review was limited to assessing the FBI’s execution of its Woods Procedures, which are not focused on affirming the completeness of the information in FISA applications.

For its part, DOJ calls DOJ IG’s report “preliminary” (seemingly ignoring that the IG claimed in that MAM and claims on its website to be continuing this part of what it calls a preliminary part of a larger review of FISA). DOJ’s Office of Intelligence did do materiality reviews of both the errors DOJ IG found and some that it found in the process of compiling these reports (in addition to the CT material misstatement described above, it found what sounds like the omission of exculpatory statements in a CI case).

But all this amounts to the more basic of the two kinds of reviews that DOJ IG did in the Carter Page case.

For these reports, DOJ continued to use the accuracy review methodology it now agrees is inadequate

As noted, all parties now agree that the Woods procedure wasn’t doing what it was supposed to do. One reason it wasn’t is because the FBI has always given agents a few weeks notice before they review one of their Woods files, allowing them to scramble to fill out the accuracy file.

But DOJ IG (perfectly reasonably) didn’t give the Crossfire Hurricane team or any of the people involved in the 29 FISA applications it reviewed here that same notice. It conducted its Woods file assessment on what was actually in the accuracy file. In the case of the Carter Page review, they found a placeholder for a 302 that said exactly what DOJ IG faulted FBI for not having evidence for, an observation about how much Stefan Halper has been paid, and publicly available details about Gazprombank, among other true claims that were nevertheless not backed up in the Woods file. It would have been child’s play — but take some work — to get proof of those and most other claims in the file. The Woods file review that DOJ IG did in the Page case — and almost certainly, the review of the 29 files — tested whether the Woods procedures were being adhered to at all, not whether the Woods procedure effectively ensured only documented claims made it into a FISA application.

If you’re going to rely on the Woods procedure as an accuracy tool, that’s what reviews need to do, because otherwise they’re doing nothing to test the accuracy of the reports.

And DOJ now agrees. In its June filing, DOJ committed to changing how it does accuracy reviews starting in September (maybe). Starting then, agents will get no notice of a review before it happens, and the accuracy rate of that no-notice review will be tracked along with the accuracy once an agent is given time to chase down the documentation he didn’t include the first time.

NSD has determined that commencing with accuracy reviews starting after September 30, 2020, it will not inform the FBI field offices undergoing NSD oversight reviews which applications will be subjected to accuracy reviews in advance of those reviews. This date is subject to current operational limitations the coronavirus outbreak is imposing. NSD would not apply this change in practice to accuracy reviews conducted in response to a request to use FISA information in a criminal proceeding, given the need to identify particular information from particular collections that is subject to use. NSD also would not apply this change in practice to completeness reviews ( discussed further below); because of the pre-review coordination that is contemplated for those reviews.

NSD will expect that the relevant FBI field offices have ready, upon NSD’s arrival, the accuracy sub-files for the most recent applications for all FISAs seeking electronic surveillance or physical search. NSD will then, on its arrival, inform the FBI field office of the application(s) that will be subject to an accuracy review. If the case will also be subject to a completeness review, pre-coordination, as detailed below, will be necessary. The Government assesses that implementing this change in practice will encourage case agents in all FISA matters to be more vigilant about applying the accuracy procedures in their day-to-day work.

In addition, although NSD’s accuracy reviews allow NSD to assess individual compliance with the accuracy procedures, NSD’s historical practice has been to allow agents to obtain documentation during a review that may be missing from the accuracy sub-file. NSD only assesses the errors or omissions identified once the agent has been given the opportunity to gather any additional required documentation. While the Government believes that, in order to appropriately assess the accuracy of an application’s content, it should continue to allow agents to gather additional documentation during the accuracy review, it assesses that this historical practice has not allowed for the evaluation of how effective agents have been at complying with the requirement to maintain an accuracy sub-file, complete with all required documentation.

As a result, NSD will tally and report as a part of its accuracy review process all facts for which any documentation, or appropriate documentation, was not a part of the accuracy sub-file at the time the accuracy review commenced.

That said, that’s not how DOJ did these reviews. In fact, John Demers emphasized this fact in his statement claiming victory over these reviews.

In addition, when the OIG found a fact unsupported by a document in the Woods file, the OIG did not give the FBI the opportunity to locate a supporting document for the fact outside the file.

Indeed, that’s not the only thing that DOJ did to help DOJ clean up DOJ’s shitty performance on DOJ IG’s review of their work. After FBI Field Office lawyers got the DOJ IG assessment, they pulled together the existing documentation, then DOJ’s OI worked with agents to fill in what wasn’t there. In fact, DOJ even got an extension on the second report because DOJ and FBI agents were still working through the files, suggesting it took up to three months of work to get the files to where DOJ was willing to tell FISC about them.

In other words, whereas the Crossfire Hurricane team got judged — by Bill Barr’s DOJ — on what was in the Woods file when DOJ IG found it, Bill Barr’s DOJ is judging Bill Barr’s DOJ on what might be in a Woods file after agents have up to three months to look for paperwork to support claims they made as long as six years ago.

DOJ disagreed with DOJ IG’s finding of error about 46% of the time

Finally, DOJ and DOJ IG did not use the same categories of information to track errors on the Woods file reviews, and one of the most common ways they dismissed the import of an error was by saying that DOJ IG was wrong.

The MAM divides the errors it found into three categories: claims not supported by any documentation, claims not corroborated by the supposed back-up, and claims that were inconsistent with the supporting documentation.

[W]e identified facts stated in the FISA application that were: (a) not supported by any documentation in the Woods File, (b) not clearly corroborated by the supporting documentation in the Woods File, or (c) inconsistent with the supporting documentation in the Woods File.

In addition to the two material errors they found, DOJ claims the errors they found fall into five categories (described starting on page 10):

- Non-material date errors

- Non-material typographical errors

- Non-material deviations from the source documentation

- Non-material misidentified sources of information

- Non-material facts lacking supporting documentation

But to get to that number, DOJ also weeded out a number of other problems identified by DOJ IG via three other categories of determination reflected in the up to three month back and forth with OI:

- Claims made that were substantiated by documents added to the file after DOJ IG’s review

- Claims that, after reviewing additional information, OI “determined that the application accurately stated or described the supporting documentation, or accurately summarized other assertions in the application that were supported by the accuracy subfile”

- Claims not backed by any document, but for which “the supporting documentation taken as a whole provided support for the fact in the application”

DOJ doesn’t count those instances in its overview — as distinct from individual narratives — of the report (indeed, the scope of added documentation is not qualified at all). And while the DOJ fillings say FBI described that it added documentation to the file in the redacted FBI declaration for FISC, it’s not clear whether it told FISC what it added and how much and where and when it came from (FBI has been known to write 302s long after the fact to document events not otherwise documented in real time).

Here’s what all this looks like in one table (FBI did what is probably a similar table, but it’s classified). Note that DOJ IG used still different categories for the Carter Page review: “Supporting document does not state this fact,” which is probably the same as their “not clearly corroborated” category. In my table, I’ve counted that as a “lacking documentation error.”

There are several takeaways from this table.

First, the numerical discrepancy provides some idea of how many errors DOJ IG found that DOJ made go away either by finding documentation for them, or by deciding that DOJ IG was wrong. DOJ IG said it found an average of 20 errors in the 25 applications it was able to review, or 500 total. DOJ says it found 63 errors in the June report and 138 errors in the July Report, over a total of 29 applications (they did a review of the four files for which DOJ IG was provided with no Woods file, so had 4 more files than DOJ IG).

My numbers are off by 3 from theirs, which might be partly accounted for recurrent errors in a reauthorized application or lack of clarity on DOJ’s narrative. Or maybe like DOJ, I subtracted 48 from 138 and got 91.

Approximately 48 of these 138 non-material errors reflect typographical errors or date discrepancies between an assertion in an application and a source document. Of the remaining 91 non-material errors or unsupported facts, four involve nonmaterial factual assertions that may be accurate, but for which a supporting document could not be located in the FBI’s files; 73 involve non-material deviations between a source document and an application; and 13 involve errors in which the source of an otherwise accurate factual assertion was misidentified.

But my count shows that DOJ simply declared DOJ IG to be wrong 151 times in its assessment that something was an error, with an amazing 35 examples of that in one application, and of which 14 across all applications were instances where DOJ couldn’t find a document to support a claim (not even with three months to look), but instead said the totality of the application supported a claim.

Claiming that the totality of an application supports a claim, while being unable to find documentation for a discrete fact, sure sounds like confirmation bias.

And in the up to three months of review, FBI found documentation to support upwards of 130 claims that originally were not supported in the Woods file. In other words, these weren’t errors of fact — they were just instances of FBI not following the Woods procedure.

We know that if the Crossfire Hurricane team had been measured by the standard DOJ did in these filings, it would have done better than most of these applications (again, only with respect to the Woods file). That’s because, aside from the four claims that rely on intercepted information (which is not public), there is public documentation to support every claim deemed unsupported in the report but three: the one claiming that James Clapper had said that Russia was providing money in addition to the disinformation to help Trump.

The DNI commented that this influence included providing money to particular candidates or providing disinformation.

And the two claiming that Christopher Steele’s reporting had been corroborated, something the DOJ IG Report lays out at length was not true in the terms FBI normally measured. Except, even there, Steele handler Mike Gaeta’s sworn testimony actually said it had been. He described jumping when Steele told him he had information because he was a professional,

And at that time there were a number of instances when his information had borne out, had been corroborated by other sources.

He also provided a perfectly reasonable explanation for why Steele’s reporting was not corroborated in the way DOJ IG measured it in the report: because you could never put Steele on a stand, so his testimony would never be used to prosecute people.

From a criminal perspective and a criminal investigative kind of framework, you know, Christopher Steele and [redacted] were never individuals who were going to be on a witness stand.

In other words, while it appears that DOJ cleaned up many of the errors identified by DOJ IG by finding the documentation to back it over the course of months, the public record makes it clear that Crossfire Hurricane would have been able to clear up even more of the Page Woods file.

The exceptions prove the rule. There are, as my table notes, two or three claims that do not accurately describe what the underlying document says, claiming:

- That Page never refuted the claims against him (he had, and in many cases, was telling the truth in his refutations)

- That Steele told the FBI he never shared information with anyone outside his “business associate” [Fusion] and the FBI (he also shared it with State, as other parts of FBI had been told)

- That in his first FBI interviews Papadopoulos admitted he had met with Australian officials but not that he discussed Russia during those meetings (it’s unclear how accurate this claim is)

Assume the last bullet (used just once) reflects the redacted parts of Papadopoulos’ 302s even though it does match his current statements, that nevertheless leaves you with an error rate on arguably the worst category — misrepresenting your evidence — of 2 or 3 per application. The first two of these are the Woods file errors that turned out to have a tie (a significant one in the first bullet) with the material reasons why some of the files were withdrawn. They’re the two errors in the Woods file that most directly tied to omitted evidence in the application that would lead to their withdrawal.

Of the 29 applications reviewed by DOJ, 12 of them have 3 or more “deviations from the source” material. One has 14 and another has 15.

So on the worst measure that this review actually did measure, the one that on Page’s application tied most directly to reasons to withdraw the application, Page’s application actually was within the norm.

It may well be that when all the reviews are done, DOJ will have proof that Carter Page’s application was an exceptionally bad application. Certainly, the material misstatements may end up being worse.

But the only thing this apples to oranges comparison of the Page methodology and the traditional DOJ methodology has proven is that — as a matter of the Woods file reviews — Bill Barr has used a different standard for Bill Barr’s DOJ than he has with Crossfire Hurricane. And that if the Page file had been treated as all the others were, from a Woods file perspective, it actually wouldn’t look that bad.

It also shows that when Bill Barr’s DOJ wants to continue spying on Americans who don’t happen to be associated with Donald Trump, he’s happy to argue that Michael Horowitz’s very legalistic reviews of the sort that did Andrew McCabe in are wrong.

Updated for clarity.