On Joshua Schulte’s Alleged Substantial Amount of CSAM … and Other Contraband

Yesterday, Judge Jesse Furman docketed a letter, impossibly dated March 23, updating him on the investigation into the Child Sexual Abuse Material allegedly found on WikiLeaks Vault 7 source, Josh Schulte’s discovery computer, six months ago (see this post for an explanation).

It described more about the CSAM material found on Schulte’s computer: The FBI had found “at least approximately 2,400 files on the laptop … likely containing CSAM.”

With respect to assertions that Joshua Schulte, the defendant, has made about the discovery laptop—that the laptop does not contain CSAM, that any CSAM appears only in thumbnails, or that the CSAM was maliciously or inadvertently loaded onto the laptop by the Government. See, e.g., D.E. 998 at 3 (pro se letter to the Court dated Dec. 21, 2022), 5 (pro se letter to the Court dated Jan. 5, 2023)—the Government is able to confirm the following: at least approximately 2,400 files on the laptop have been identified to date as likely containing CSAM. Those files include full images, and are not limited to thumbnail images. Moreover, the Government did not copy discovery materials onto the defendant’s laptop. In 2021, former defense counsel copied discovery and trial materials onto the laptop, which was then reviewed by personnel from the U.S. Attorney’s Office for security compliance before making a file index and providing the laptop to the Metropolitan Correctional Center (“MCC”), where the defendant was then in custody. The CSAM on the laptop was not provided by the Government or the result of Government action.

That, by itself, doesn’t tell us a lot more than we learned in an October filing, which explained that the FBI had found, “a substantial amount” of suspected CSAM.

Indeed, the letter focuses on debunking two counterarguments Schulte has made since, which is one of the reasons Furman docketed it after DOJ submitted it ex parte: “[T]his letter responds directly to assertions by Mr. Schulte,” Furman observed.

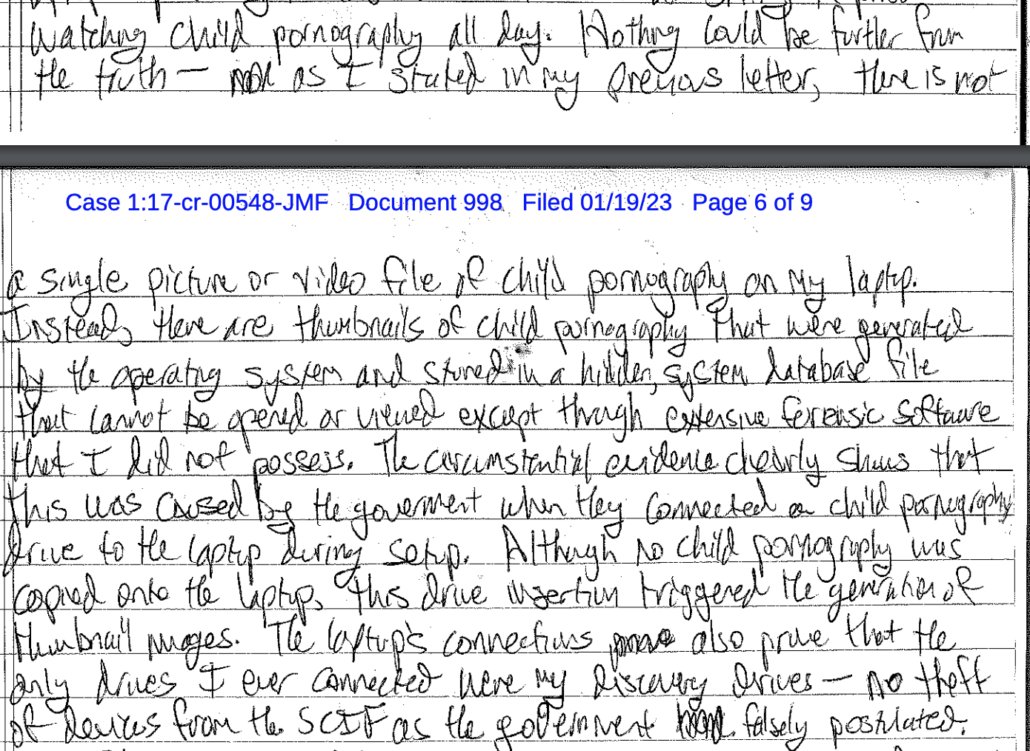

The government was debunking a claim made by Schulte that the government had caused the CSAM — but only thumbnails — to be loaded onto his discovery computer by “connect[ing] a child pornography drive to the laptop during setup.”

Schulte repeated and expanded — at great, great length — that theory in a set of filings dated March 1 but just loaded to the docket today.

The government response, effectively, was that they made an index of the files as the computer existed when it was turned over to MCC in 2021, calling Schulte on his claim that he was framed with CSAM.

Ultimately both sides will be able to present their claims to a jury.

But there are several other reasons I’m interested in the letter and related issues.

The government’s working theory when they first revealed this last fall, was that Schulte got a thumb drive into the SCIF and from that accessed the CSAM allegedly found on his home computer six years ago, presumably just to have it in his cell for his own further exploitation of children.

there is reason to believe that the defendant may have misused his access to the SCIF, including by connecting one or more unauthorized devices to the laptop used by the defendant to access the CSAM previously produced.

That’s because in August, they found a thumb drive attached to the SCIF laptop.

On or about August 26, 2022, Schulte was produced to the Courthouse SCIF and, during that visit, asked to view the hard drive containing the Home CSAM Files from the Home Desktop. The hard drive was provided to Schulte and afterwards re-secured in the dedicated safe in the SCIF. The FBI advised the undersigned that, while securing the hard drive containing the Home CSAM Files, they observed that an unauthorized thumb drive (the “Thumb Drive”) was connected to the SCIF laptop used by Schulte and his counsel to review that hard drive containing the Home CSAM Files. On or about September 8, 2022, at the Government’s request, the CISO retrieved the hard drive containing materials from the Home Desktop from the SCIF and returned it to the FBI so that it could be handled pursuant to the normal procedures applicable to child sexual abuse materials. The CISO inquired about what should be done with the Thumb Drive, which remained in the dedicated SCIF safe.

But in a little noticed development, during the period when FBI has been investigating how a defendant held under SAMs managed to get (we’re now told) 2,400 CSAM files onto his discovery computer, CNN reported that the network of FBI’s NY Field Office focused on CSAM had been targeted in a hacking attempt.

The FBI has been investigating and working to contain a malicious cyber incident on part of its computer network in recent days, according to people briefed on the matter.

FBI officials believe the incident involved an FBI computer system used in investigations of images of child sexual exploitation, two sources briefed on the matter told CNN.

“The FBI is aware of the incident and is working to gain additional information,” the bureau said in a statement to CNN. “This is an isolated incident that has been contained. As this is an ongoing investigation the FBI does not have further comment to provide at this time.”

FBI officials have worked to isolate the malicious cyber activity, which two of the sources said involved the FBI New York Field Office — one of the bureau’s biggest and highest profile offices. The origin of the hacking incident is still being investigated, according to one source.

DOJ still insists that former CIA hacker Josh Schulte found a way to access a whole bunch of CSAM. And in the same period, reportedly, the servers involved with CSAM investigation in the NYFO were hacked.

And while the letter released yesterday doesn’t tell us — much — that’s new about what Schulte allegedly had on his laptop, it does tell us, by elimination, which of the sealed filings in his docket are not related to the CSAM investigation.

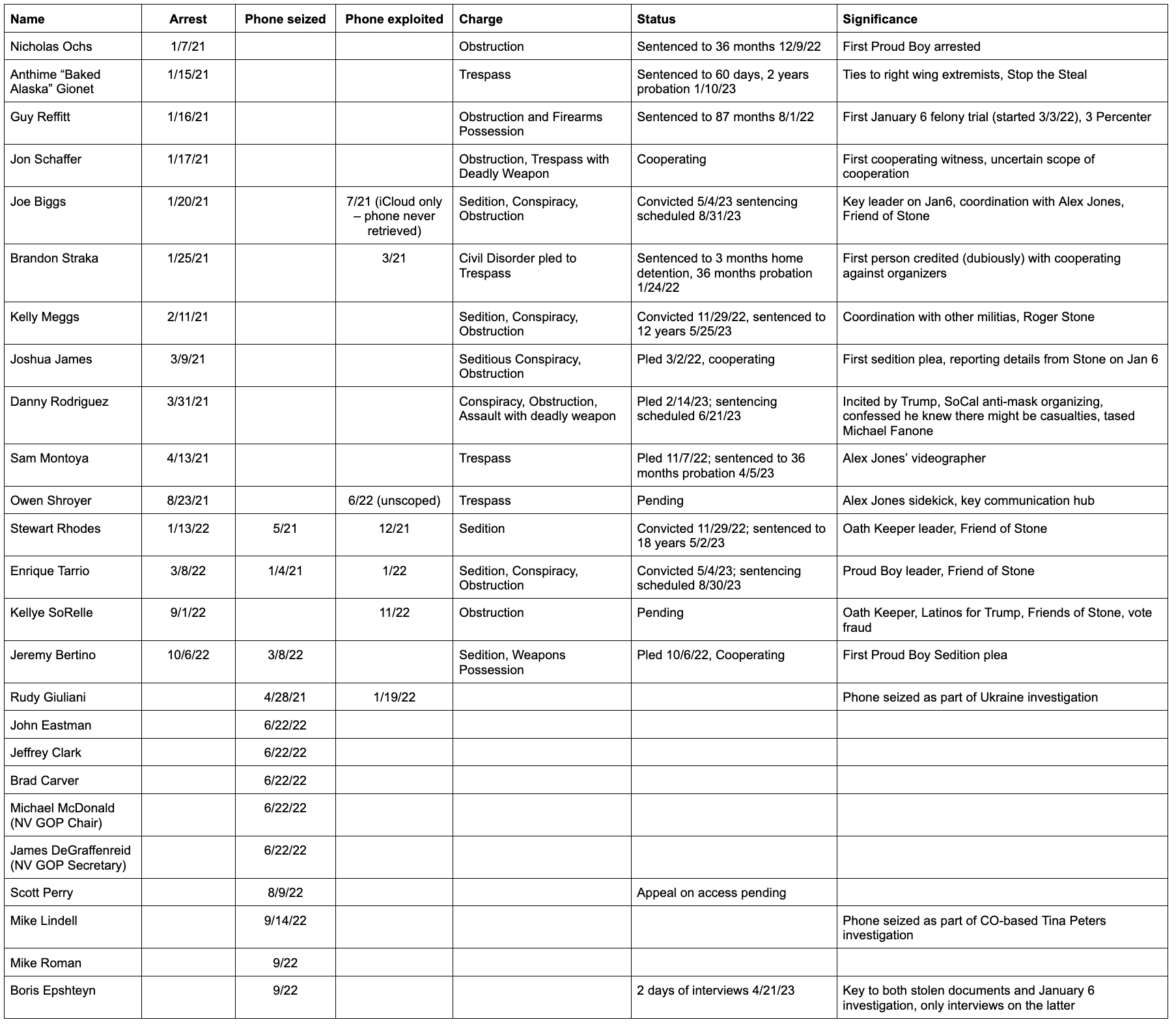

Since the October update on the investigation into Schulte, sealed documents have been filed in Schulte’s docket on the following days:

- December 15: Sealed document

- January 19: Ex parte update on CSAM investigation

- January 26: Sealed document

- March 9: Sealed document

- March 13: Sealed document

Only the January 19 letter — along with yesterday’s letter — have been unsealed. That, plus the flurry of filings in September and October, are it for the CSAM investigation. There’s something else going on in this docket, four sealed documents worth.

Indeed, in those very long set of filings mentioned above, both dated February and finalized March 1, both docketed today, Schulte alluded to something beyond CSAM.

Judge Furman has begun claiming that there are other vague misuses or misbehavior on the laptop.

He must not have read the September and October letters very closely, because they describe there was a warrant that preceded the discovery of the CSAM.

The warrants that we know of include the following:

- July 27: Contempt and contraband

- September 22: CSAM expansion warrant

- October 4: MDC cell and devices

- October 4: CSAM devices (for the devices used in the SCIF)

- October 5 and 6 (authorized by protective order): Log files for devices in SCIF

Since late September, this investigation was about the “substantive” amounts of CSAM found on a computer possessed by Schulte.

But before that it was based on suspicions of contraband.

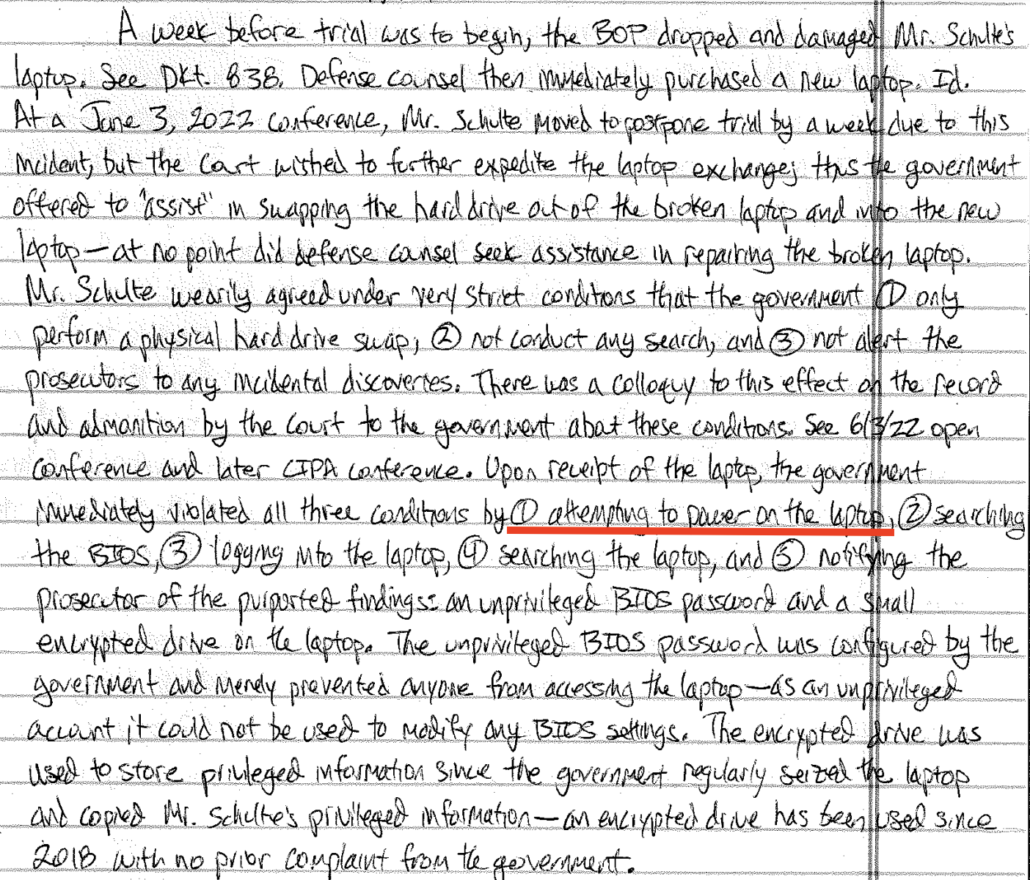

That stems, in significant part, from a search of the computer DOJ did in June, when Schulte turned it over claiming it had been dropped.

It hadn’t been dropped. It needed to be charged. Indeed, in the interminable motions filed today, Schulte treated plugging in a laptop as some kind of due process violation.

Plugging in a laptop should in no way compromise the privacy of a laptop. But it did raise real questions about the excuse Schulte offered in an attempt to get a second laptop (one he effectively got once trial started anyway).

Needless to say, his description of what happened with the BIOS password differs from the government’s, as provided last June.

First, with respect to the defendant’s discovery laptop, which he reported to be inoperable as of June 1, 2022 (D.E. 838), the laptop was operational and returned to Mr. Schulte by the end of the day on June 3, 2022. Mr. Schulte brought the laptop to the courthouse on the morning of June 3 and it was provided to the U.S. Attorney’s Office information technology staff in the early afternoon. It appears that the laptop’s charger was not working and, after being charged with one of the Office’s power cords, the laptop could be turned on and booted. IT staff discovered, however, that the user login for the laptop BIOS1 had been changed. IT staff was able to log in to the laptop using an administrator BIOS account and a Windows login password provided by the defendant. IT staff also discovery an encrypted 15-gigabyte partition on the defendant’s hard drive. The laptop was returned to Mr. Schulte, who confirmed that he was able to log in to the laptop and access his files, along with a replacement power cord. Mr. Schulte was admonished about electronic security requirements, that he is not permitted to enable or use any wireless capabilities on the laptop, and that attempting to do so may result in the laptop being confiscated and other consequences. Mr. Schulte returned to the MDC with the laptop. [my emphasis]

Here’s more background on all the funky things that happened with this laptop that led me to suspect something was going on last summer.

Anyway, the government claims it found a whole bunch of CSAM on Schulte’s computer. But there’s also something else going on.

We may find out reasonably soon. The impossibly dated filing from this week promised an update in a week, which (if the impossibly dated filing was actually dated March 21) might be Tuesday.

The Government expects to provide the Court with a supplemental status letter in approximately one week.

At the same time that CIA hacker Josh Schulte was allegedly finding a way to load CSAM onto his discovery laptop, the local FBI office’s CSAM servers were hacked.

That might be a crazy coincidence.

Update: DOJ filed an ex parte update today, which may or may not have to do with the CSAM investigation.