Self-imagined IRS whistleblowers, Gary Shapley and Joseph Ziegler, continue to engage in an information campaign that not only hasn’t provided real evidence for impeachment, but also must be creating real difficulties for David Weiss as he attempts to charge the tax case against Hunter Biden.

The House Ways and Means Committee released a slew of documents provided by the IRS Agents the other day in advance of Thursday’s Impeachment Clown Show. Below, I’ve laid out just the documents pertaining to the investigation (that is, the purported topic of their whistleblower complaint), along with explanations of what the documents show. There are a bunch of other investigative documents (Shapley appears to have let Ziegler assume most of the legal risk of releasing the bulk of the new IRS and grand jury documents), some of which reflect a real sloppiness about parts of the investigation, which would pose still more problems charging this case.

I also plan to write a follow-up post laying out Gary Shapley’s actions in advance of the October 7, 2022 meeting. They show that the items he claimed presented a new “red line” for him in that meeting had instead been raised with him months earlier. He came into the meeting with an agenda — notably, that David Weiss should ask to be appointed Special Counsel (as opposed to Special Attorney) — and raised non-sequiturs given the posture of the case at the time.

As to some other key claims the IRS Agents have made, especially against Lesley Wolf, the record provides countervailing evidence on those too.

As noted, for example, the decision not to take overt steps in 2020 came directly from Donald Trump’s Deputy Attorney General’s office, from someone — Richard Donoghue — who knew first-hand about Russian efforts to tamper in the election by focusing on Hunter Biden. The IRS Agents and Republican Members of Congress have blamed Wolf for that.

One key complaint is that Gary Shapley wasn’t permitted to surprise Hunter Biden during the day of action on December 8, 2020. But as Wolf represented it in a call Ziegler memorialized on December 11, the norm would have been to work through Hunter’s lawyers for an interview. Her support of going with only a heads up to the Secret Service was a deviation from that norm, she claimed. There’s no support in these documents for Shapley’s claim (and Ziegler’s hearsay claim) that the Transition Team got a heads up from DOJ, so if Shapley had a credible source for it, it wasn’t documented notice.

Another complaint — one Republicans in Congress can’t let go — was that Wolf used a subpoena to get the contents of a storage facility Hunter had rather than a search warrant. But a month earlier than that, the plan wasn’t to get a warrant, it was to do a consent search. When Ziegler pitched her on a search warrant after the Rob Walker interview, he wanted to do the search immediately, within a week, in spite of what she represented would be the onerous approval process to get a warrant. According to what Ziegler records Wolf saying, all the lawyers involved in this decision agreed with her (not surprisingly, given that a taint review after going overt would involve the same level of defense attorney involvement as a subpoena would). When the IRS escalated this issue on December 14, they still didn’t know how a taint review would work in the Fourth Circuit, meaning they had not yet tested Wolf’s claims.

Importantly, the reason Ziegler thought it so important to do a search of the storage facility rather than serve a subpoena is that he wanted to find proof of foreign bank accounts, something for which Wolf claims there was no evidence.

Ziegler brought up the potential for foreign accounts and the records that he had seen thus far that indicate there are foreign accounts involved in this case. Wolf said that there is no indication what‐so‐ever that the Subject has foreign accounts and that any records related to that would be turned over [pursuant to subpoena].

Even in the most recent Republican documents, reflecting what Ziegler and Shapley turned over, I’m aware of no such evidence. The foreign payments Republicans claim are so suspect went right through corporations established in Delaware. Many of the payments appear to have gone through the same Wells Fargo accounts on which Ziegler predicated this investigation five years ago. And the IRS appears to have checked (one, two) with the most likely havens — Hong Kong and the Cayman Islands — about whether there were foreign accounts. I haven’t read all the investigative documents or the tax returns and investigators may find something else, but if this is correct, then it’s one hell of a money laundering claim these guys are chasing, consisting of payments through corporations headquartered right in Delaware and payments through Hunter’s main bank account.

It was already clear from Ziegler’s testimony that his complaints about delays in interviews in 2021 didn’t account for Wolf’s efforts to prioritize more important investigative steps, such as getting approval for a subpoena for Hunter’s attorney, George Mesires, rather than focusing on interviews with sex workers. The interview with Mesires took another year to schedule. But one set of emails from the time show it was Ziegler’s IRS supervisor, and not Lesley Wolf, that pushed back on his plans for interviews; the supervisor suggested he bring in “collaterals” to do some of the investigative work rather than do it all himself.

The IRS Agents and Republican Members of Congress similarly keep complaining that David Weiss let the statute of limitations expire on the 2014 and 2015 charges most closely focused on Burisma. There was already evidence (most especially in the hand-written notes that Shapley only belatedly shared) that it wasn’t so much that Weiss “let” SOLs expire, but that he made a prosecutorial decision — one Shapley refused to abide by — not to charge those years. Lesley Wolf first started raising questions about the sufficiency of the evidence in May 2021. This new trove of documents show that Shapley had been informed that DE USAO was disinclined to charge those years more than two months before October 2022, and again in August 2022. There is a good deal of evidence that Shapley’s manufactured panic about “letting” SOLs expire instead is an expression of disagreement with a prosecutorial decision.

Perhaps worst of all, the depiction the IRS Agents have made of Lesley Wolf does not reflect what appears in these documents, which show her to be more supportive of them than they claimed. On September 21, 2020, Wolf followed up immediately when the FBI showed reluctance to pursue parts of the investigation. In October 2020, she was supportive of the IRS’ wishes to do the Day of Action interviews sooner rather than later. In December 2021, she made a point of commending all the work Ziegler had done on the case. In June 2022, David Weiss recognized Ziegler’s work. In August 2022, Wolf noted that Ziegler was busy dealing with a family issue and empathized, “know I am thinking of you and sending good thoughts.”

The one thing Wolf absolutely did push back on was the IRS Agents’ efforts to conduct a campaign finance investigation of the funds Kevin Morris provided to Hunter to pay off his taxes. At one point, her request that they prioritize the 2014 tax case first (which she said hadn’t been proven yet) was depicted as obstruction. At another — in Shapley notes that again appear to conflict with what he was writing in the official record — she provided several good legal reasons not to pursue the case, including that any “donation” from Morris to Joe Biden via Hunter was even more attenuated than the John Edwards case that failed. By recording and publicly releasing Wolf noting that the law was not clear on this issue, Shapley will make it almost impossible to charge, because anyone charged would simply point out that even DOJ agreed it wasn’t a clear campaign finance donation. And what the IRS Agents otherwise portray as Wolf’s disinterest in involving Public Integrity (PIN) because they would take authority away from her was (here and elsewhere) instead described as PIN requiring another layer of approvals, precisely the thing that IRS Agents were complaining about elsewhere.

The IRS Agents’ recriminations of Lesley Wolf have gotten her targeted with serious threats. And yet, their own record doesn’t substantiate the claims they have made against her.

Update: Corrected which countries IRS reached out to: the Caymans and Hong Kong, not Cyprus.

Timeline

September 21, 2018: Suspicious Activity Report from Wells Fargo.

October 31, 2018: Primary investigation initiated into other entity.

November 1-2, 2018: Request of support for SAR, only other agency investigating was DA office.

December 10, 2018: Primary investigation initiated into Hunter Biden.

January 18, 2019: Update from Wells Fargo on SAR.

Around February 2019: SSA informs Ziegler that DE USAO looking into SAR.

March 28-29, 2019 Exhibit 400: April 26, 2019, FBI FD 302, re: March 28, 2019, Interview with Gal Luft. It appears likely there were two 302s of these interviews (possibly three) because Luft’s alleged lies don’t appear in unredacted form in this one.

April 12, 2019: Package submitted to DOJ-Tax

April 15, 2019 Exhibit 206: April 15, 2019, Email from Joseph Ziegler to Jessica Moran, Subject: Approx. Timeline. This shows the above timeline, about which Ziegler was not clear in his testimony.

April 29, 2019 Exhibit 207: April 29, 2019, Email from Matthew Kutz to Kelly Jackson, cc’ing Joseph Ziegler and Christopher Wajda, Subject: Robert Doe – FYI Venue issue. Kutz is the person to whom Ziegler attributed his understanding that Barr had assigned this to DE USAO himself, before backing off that claim. Kutz is also the person who was documenting 6A and inappropriate influence on the investigation. Ziegler provides none of that.

August 5-7, 2020 Exhibit 202: August 5-7, 2020, Emails Between Joshua Wilson, Lesley Wolf, Carly Hudson, cc’ing Susan Roepcke, Michelle Hoffman, Joseph Ziegler, and Joseph Gordon, Subject: BS SW Draft. This was a warrant for BlueStar emails. AUSA Wolf objected not just to the mention of Joe Biden in the warrant (which is the only thing Ziegler leaves unredacted), but also to a great deal of stuff that was outside scope of the warrant. The SDNY FARA investigation was active in this period, which may be why other stuff was included, but in short order, even the IRS seemed to concede the SDNY FARA investigation into CEFC (the one that would rely on Gal Luft’s interview) was not viable.

Exhibit 203: Draft of B[lue]S[star email] Warrant.

September 3-4, 2020 Attachment 2: September 3-4, 2023, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler, Lesley Wolf, cc’ing Carly Hudson, Jack Morgan, Mark Daly, Joshua Wilson, Susan Roepcke, Alyssa Ruisard, Antonino Lo Piccolo, Christine Puglisi, Stefania Roca, Michael Dzielak, Gary Shapley, and Joseph Gordon, Subject: Today’s Agenda. This is an incredibly helpful list of where key legal process stood:

- 4 iCloud backups (Ziegler asked whether location data was necessary, which he and Shapley suggested was mandatory before)

- Relevancy review of iPhone Backup (which tells you they were still scoping the phone when they got the iCloud warrants)

- Search warrant for BlueStar (about which investigators disagreed in August)

- Supplemental email search warrant (unclear on which account)

- DropBox search warrant (which wouldn’t be served for some time, but which seems to have been an attempt to get emails they knew of but didn’t have)

- Discussion of 2703-D orders (metadata) for two accounts belonging to Vadym Pozharskyi and one to Devon Archer; elsewhere Ziegler relies on the “laptop” for emails involving the two

The agenda also notes investigative developments involving SDNY (the FARA investigation), Pittsburgh (the FD-1023), and Comerica.

September 3-4, 2020: Memo of Meeting. At this meeting, there was a discussion of keeping Hunter Biden’s name off overt requests, to which Ziegler objected (as if he wanted it to be discovered). There’s a discussion of whether the investigation would continue or not after the election, which Wolf said it would. Wolf attributed sensitivities to Richard Donoghue. Note: Shapley doesn’t say who was involved in the follow-up call on September 4.

September 21, 2020 Attachment 3: September 21, 2020, IRS CI Memorandum of Conversation Between Gary Shapley and Mark Daly, Authored by Gary Shapley. This memorializes a meeting earlier that day in which Joe Gordon expressed uncertainty among FBI management about how many interviews they would participate in after the election. Lesley Wolf pushed back hard on this. This memo reflects double hearsay (Wolf to Mark Daly to Shapley) blaming Special Agent Josh Wilson for the reluctance on investigating Hunter, because he had just moved back to Wilmington with his family. Shapley also memorializes a call to his ASAC about the details. This is another instance where Wolf was pushing the investigation hard.

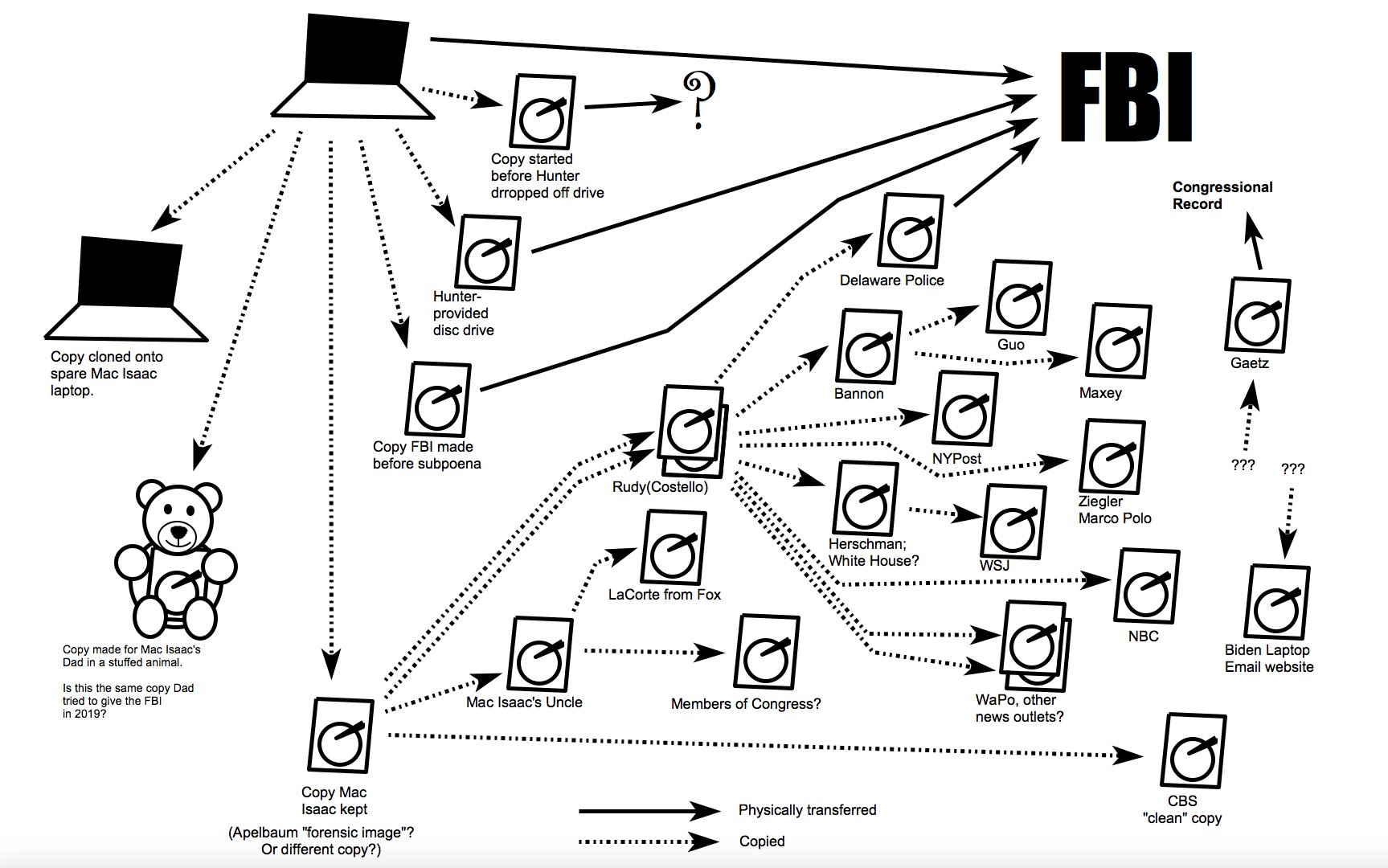

October 19, 2020 Attachment 5: October 19, 2020, Email from Gary Shapley to Lesley Wolf, Subject: Computer. This is an email Shapley read, in part, in his testimony, regarding IRS’ need to know what was going on with the laptop. Ironically, he notes that there may be specific disclosure limitations tied to the IRS warrant, a concern with which he has since dispensed.

October 21, 2020 Attachment 4: October 2, 2020, Emails Between Lesley Wolf, Joseph Ziegler, Gary Shapley, and George Murphy, Subject: Dates. This reflects ongoing discussion about when to do the day of action, in an attempt to avoid interviewing Hunter in Delaware, as opposed to LA. Lesley Wolf was again supportive of Shapley’s goals to do the interviews sooner rather than later.

October 21, 2020 Exhibit 210: October 21, 2020, Emails Between Jack Morgan, Lesley Wolf, cc’ing Mark Daly and Carly Hudson, Subject: Mann Act. Jack Morgan emails Lesley Wolf regarding nine communications, two with traffickers, that he says may support Mann Act exposure. In only two cases was the travel confirmed. There are no dates in this list. Three instances include travel to Massachusetts (and so might coincide with the apparent hijacking of Hunter’s digital identity while he was in Ketamine treatment).

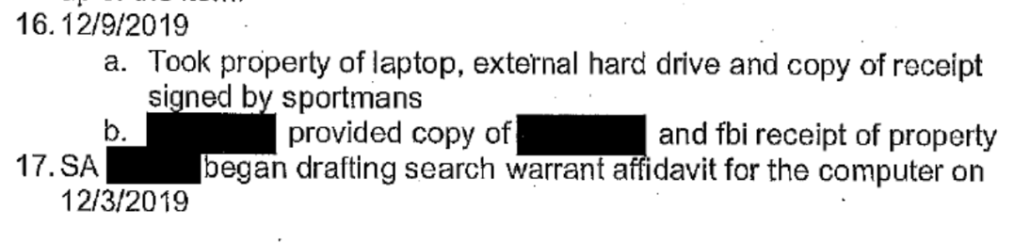

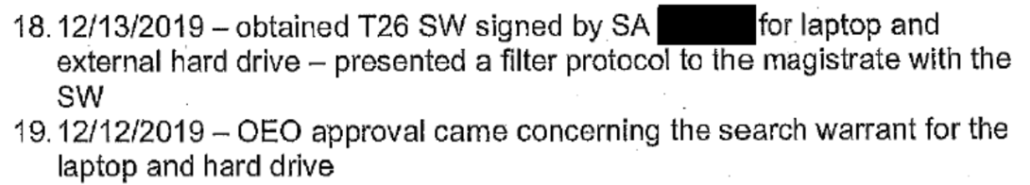

October 22, 2020: Notes on laptop. As noted, Shapley wildly misrepresented what the notes on the laptop actually say. They show that 10 months after accessing the laptop, the FBI still hadn’t done basic things to validate the content on the laptop had not been tampered.

October 22, 2020 Attachment 6: October 22, 2020, IRS CI Memorandum of Conversation between Prosecution Team, Authored by Gary Shapley. Shapley records Wolf as saying that there would not be a warrant on the DE residence. He does not record why. He also records the briefing on the Pittsburgh lead, ordered up by PDAG (Donoghue). This meeting happened an hour after the laptop meeting, but Shapley treats it as a separate meeting (and doesn’t say who attended).

October 23, 2020 Exhibit 400A: Tony Bobulinksi FBI FD-302 Interview Memorandum. This interview happened on October 23, 2020; Bobulinski went straight from the White House to self-report at the FBI. He repeatedly refused to let the FBI image his phones. It certainly doesn’t help Bobulinski’s credibility as a witness.

October 23, 2020 Exhibit 400B: Attachment Tony Bobulinksi FBI FD-302 Interview Memorandum.

November 2-9, 2020 Attachment 7: November 8-9, 2020, Emails Between James Robnett and Kelly Jackson, cc’ing Michael DePalma, George Murphy, and Gary Shapley, Subject: 1 page brief needed. The day after networks called the election for Joe Biden, the Deputy Chief of IRS-CI ordered the team to put together a one-page summary of the Hunter Biden investigation, to be delivered to him by Tuesday, November 10.

November 9, 2020 Attachment 8: November 9, 2020, Email from Kelly Jackson to Gary Shapley, cc’ing George Murphy, Subject: Recipient of the 1 pager. Effectively, the IRS team checked how far this would circulate before drafting.

~November 9, 2020 Attachment 9: Sportsman Investigation, IRS CI One-Pager. This appears to be a draft, not the final, as there are inline questions and answers. This provides a good summary of where the investigation was, notes that the FARA investigation pertained to CEFC (and that investigators planned no overt steps). It also says that the plan was to do a consent search of the storage facility (and a residence, though it’s not clear which one), which puts the later dispute in context.

December 8, 2020 Exhibit 401: December 8, 2020, Transcribed Interview of John Robinson Walker.

December 8-9, 2020 Exhibit 204: December 8-9, 2020, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler, Lesley Wolf, Mark Daly, Carly Hudson, Jack Morgan, cc’ing Christine Puglisi and Gary Shapley, Subject: Storage Location Warrant. The discussion returns to a warrant for the storage facility outside of DC (in VA). Ziegler says he wants to execute it the following week. Wolf tries to explain that there will be too many approvals required and heavy filter requirements because the facility is in the Fourth Circuit.

December 10, 2020 Attachment 10: IRS CI Monthly Significant Case Report, Subject Name: Robert Hunter Biden, December 2020. This periodic report (Shapley only provided two, raising questions about whether there were others) includes the most substantive description of how the investigation was predicated off sex workers. Shapley bitches about Wolf forgoing the approvals and instead applying the subpoena to the storage facility (without noting that the initial plan was to do a consent search). He says that the only viable charges at that point were tax charges (meaning the SDNY FARA charges didn’t flesh out). This report also notes the election meddling allegations. Shapley also bitches that prosecutors aren’t responding to Congressional inquiries, a totally inappropriate stance, one he would repeat in a later report. He blames the December 2020 leak on DOJ, with no explanation. Unclear whether this really is dated December 10, before the December 11 call with Wolf.

December 11, 2020 Exhibit 205: Joseph Ziegler’s Notes re: Phone Call with Lesley Wolf About the Storage Unit Warrant. The notes of this call actually debunks several things Ziegler has claimed. Wolf notes that the normal way to interview Hunter would be to call his lawyers, but she worked hard to go through just Secret Service. She also notes that all lawyers involved agreed subpoenaing for the documents was the appropriate thing to do.

December 14, 2020 Attachment 11: December 14, 2020, Emails Between Kelly Jackson, George Murphy, and Gary Shapley, Subject: SM – call with DFO today. This escalated matters on the facility to Deputy Commissioner. At that point, one of the IRS people didn’t even knew how a taint would work after a search.

December 15, 2020 Attachment 12: December 15, 2020, FBI Electronic Communication, Title: Attempted Interview: Hunter Biden 12/08/2020. The 302 reflecting the non-interview of Hunter. Slightly over two hours later, Hunter’s lawyers contacted the FBI.

January 26, 2021 Exhibit 315A: January 26, 2021, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler, Stefania [redacted], and Carly Hudson, Subject: Can you send me the filter terms that have been used for Relativity? For some reason, Ziegler included these filter terms, which will be very helpful to Hunter’s lawyers. Notably, there were two sets of filters: tax and FARA, which may explain the source of Ziegler’s frustration that they didn’t get all results. At that point FARA was exclusively focused on Ukraine.

Exhibit 315B: Appendix A, Filter Keywords for Google Email.

Exhibit 315C: Appendix A – Laptop, Filter Keywords for Laptop Filter.

Exhibit 315D: Appendix A, Filter Keywords for Laptop FARA Filter.

February 5, 2021 Attachment 13: February 5, 2021, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler, Lesley Wolf, Carly Hudson, Joshua Wilson, Susan Roepcke, Michelle Hoffman, Antonino Lo Piccolo, Christine Puglisi, Stefania Roca, Michael Dzielak, Matthew McKenzie, cc’ing Joseph Gordon and Gary Shapley, Subject: Agenda 2/5 Meeting @ 12:30PM. This reflects Wolf and other lawyers briefing seemingly more than one AAG (unclear whether this is Acting, or Assistant, since no one was confirmed yet). Shapley was put out that NSD asked to be briefed on the tax side of the case.

April 27, 2021 Exhibit 1E: Transcript of Recorded IRS CI Interview with Jeffrey Gelfound, re: Hunter Biden Representation Letter and Discussion of Hunter Biden 2014 Tax Return. A fragment of an interview with Hunter’s accountant regarding a representation letter signed 3 months after the initial representation. Gelfound really didn’t seem as worked up about it as the IRS.

April 27, 2021 Exhibit 1F: Transcript of Recorded IRS CI Interview with Jeffrey Gelfound, re: Alleged Gulnora Deduction. The part of the Gelfound interview regarding how the sex worker came to be deducted.

April 27, 2021 Exhibit 1J: Transcript of Recorded IRS CI Interview with Jeffrey Gelfound, re: Hunter Biden’s Tax Payments. Gelfound suggested that the payments with a lien would be paid by Kevin Morris first, possibly because of publicity.

May 2021 Attachment 14: IRS CI Monthly Significant Case Report, Subject Name: Robert Hunter Biden, Month/Year of Report: May 2021. This notes the 2021 expiration of the 2014 tax year. It states that FBI is not sold on charging decision. It says FBI is actively involving FARA. And it claims there are campaign finance violations (pertaining to Kevin Morris paying off Hunter’s taxes), which Wolf wanted nothing to dø with, in part to avoid PIN involvement. She stated that 2014 could not yet be proved beyond a reasonable doubt, which is what she wanted them to focus on.

June 14, 2021 Exhibit 1G: Interview excerpt of Gulnora. This is the interview with the sex worker payments to whom Hunter deducted. She appears to have ties to the overseas escort service, so these payments could be the ones that triggered the entire investigation. Marjorie Taylor Greene misrepresented this interview in her campaign to turn Hunter into a sex trafficker.

September 9, 2021 Exhibit 208: September 9, 2021, Email Between Joseph Ziegler, Lesley Wolf, Stefania Roca, cc’ing Carly Hudson, Jack Morgan, Mark Daly, Christine Puglisi, Michelle Ann Hoffman, Susan Roepcke, and Joshua J. Wilson, re: Frustrations with Interview Delays. Ziegler complains that some interviews with sex workers have to be put off because DOJ Tax is still approving, among other things, a subpoena for Hunter’s lawyer George Mesires.

September 10-24, 2021 Attachment 15: September 10-24, 2021, Emails Between Gary Shapley and Jason Poole, Subject: Quick Call. Shapley’s own supervisor was blowing him off too, but he did follow-up twice to complain about approvals.

September 20, 2021 Exhibit 209: September 20, 2021, Emails Between Mark Daly and Joseph Ziegler, Subject: Re: email sent to mgmt with list of 10 [redacted]. Mark Daly gets involved and seems to move these forward.

September 20, 2021 Attachment 2: September 20, 2021, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler, David Denning, Christine Puglisi, Darrell Waldon, and Gary Shapley, Subject: Travel. Here Ziegler lashes out at his own supervisor, who suggests he send a “collateral” to do interviews in LA, rather than doing them himself. Contrary to wanting to go overt in the past, he claims he is trying to keep things quiet. Ziegler writes that this is “a case I’ve worked with very little problems and only support from my management, you’re making it hard for me to do my job” (though he may have only been referencing the IRS side).

September 20, 2021 Attachment 3: September 20, 2021, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler, David Denning, Christine Puglisi, Michael Batdorf, and Gary Shapley, Subject: Travel. Ziegler escalates to Mike Batdorf. He notes, “I don’t want to put some details in this email” and also says he’s only cc’ing Shapley “because I’ve briefed him on what has happened and because he’s been my management since day 1,” which is of course false.

September 22, 2021 Exhibit 506: September 22, 2021, Emails Between Justin Cole, James Lee, James Robnett, Michael Batdorf, Darrell Waldon, and Joseph Ziegler, Subject: Sensitive Case Heads Up. CNN reached out to IRS and said they had a recent witness saying the case was almost wrapped up, claiming to having a Hunter email saying that all this would go away when his dad became President, claiming there was a plea deal. Batdorf gets the question, sends it to Ziegler, he asks if he can share with the lawyers. Batdorf asks not to share the CNN side, even though they regularly share media reports. Ziegler reports back that Wolf said no plea had been offered.

September 20-23, 2021 Exhibit 507: September 20-23, 2021, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler, David Denning, Christine Puglisi, Michael Batdorf, and Gary Shapley, Subject: Travel. Batdorf follows up again and Ziegler says “It seems to have been a miscommunication from my senior management. … I had a significant amount of trust in my prior management, and for some reason, that has gone away.”

November 16, 2021 Exhibit 1H: IRS CI Memorandum of Interview with Jeffrey Gelfound on November 16, 2021.J

November 23, 2021 Exhibit 402: John Robinson Walker FBI FD-302.

December 20, 2021 Exhibit 200: December 20, 2021, Email from Lesley Wolf to Mark Daly, Jack Morgan, Carly Hudson, Matthew McKenzie, Joseph Ziegler, Christine Puglisi, Antonino Lo Piccolo, Susan Roepcke, Michelle Ann Hoffman, Michael Dzielak, Stefania Roca, Joseph Gordon, and Joshua Wilson, Subject: Thank you! Wolf gives extra credit to Ziegler for all his work.

January 12, 2022 Attachment 16: Notes from January 12, 2022, Sportsman Call. Wolf gives good legal reasons not to pursue the campaign finance investigation, notably that the law is uncertain and the facts are even more attenuated here than they were for John Edwards. She doesn’t want to involve PIN because it would add another level of approval.

Janaury 27, 2022: Prosecution Memo. As described in Shapley’s testimony, this document is what goes through a series of approval processes.

February 15, 2022 Attachment 17: February 15, 2022, Email from Gary Shapley to Darrell Waldon, cc’ing Lola Watson, Subject: For Review/Approval: Sensitive T26 Prosecution Recommendation – SPORTSMAN – SA Ziegler. This was Shapley’s rebuttal to CT’s non-concur on prosecution, based on Hunter’s addictions. Though Shapley (and especially Ziegler) has elsewhere stated clearly that Hunter was totally incapacitated in this period, Shapley now claims, “the universe of his conduct clearly indicated he was lucid during his periods of insobriety and therefore a blanket lack of willfulness defense to the pattern of conduct is not reasonable nor logical.”

May 13, 2022 Attachment 18: May 13, 2022, Email from Gary Shapley to Michael Batdorf and Darrell Waldon, which Gary Shapley Forwarded to Joseph Ziegler and Christine Puglisi, Subject: Sportsman – 3rd DOJ Tax – Taxpayer Conference Delayed. Because of a delay in the tax conference at which the prosecution recommendation would be presented, Shapely pitches briefing Jason Poole and David Weiss on it in advance.

June 14-15, 2022 Exhibit 314: IRS CI Presentation re: Sportsman Investigation “Robert Doe,” Tax Summit, June 14-15, 2022. This is the slide deck presenting the case. Most of it — three pages — describe spin-off investigations. It shows the main remaining steps were to establish venue somewhere besides Delaware and get discovery production; at this moment, Shapley was refusing to turn over discovery production to DOJ.

June 30, 2022 Exhibit 1K: June 30, 2022, Email from Matthew Salerno to Mark Daly, Lesley Wolf, Carly Hudson, Jack Morgan, cc’ing Chris Clark, Brian McManus, and Timothy McCarten, re: 2018 Tax Defenses Proffered, wh ich Mark Daly Forwarded to Joseph Ziegler, Michelle Ann Hoffman, Christine Puglisi, and Michael Dzielak. This is Mark Daly forwarding Hunter’s lawyers’ rebuttal on some of the 2018 deductions, explaining while none of Hunter’s efforts to develop businesses worked, he was attempting. Ziegler has claimed there’s contrary evidence (from James Biden) in the record, but none of that is definitive and James Biden testified his memory wasn’t great on the matter.

June 21-28, 2022 Exhibit 201: June 21-28, 2022, Emails Between David Weiss, Joseph Ziegler, and Gary Shapley, cc’ing Lesley Wolf, Carly Hudson, Jack Morgan, and Mark Daly, Subject: Sportsman Request. After thanking Ziegler for all his work, Weiss asks IRS to have a revenue agent rerun all the loss numbers for 2014 and 2015. He asks for that, first, because that’s what is normally done, and second, because, “at trial we are going to need a testifier on this issue and that testifier can’t be Joe.” While Ziegler ultimately complied with Weiss’ request, Ziegler first appears to have redone the analysis himself. This email will give Hunter’s attorney cause to question the revenue analyst about Ziegler’s role in these numbers, if this ever gets charged.

July 29, 2022 Attachment 19: Notes from July 29, 2022, Sportsman Call. This includes details of the state of the investigation, including mentions of approval for a new prong of FARA investigation, with references to SDNY (CEFC) and Romania. The outstanding witnesses include George Mesires and family members, including James Biden (and possibly Hallie Biden, though that’s redacted), though an August 18 email lists Mervyn Yan among those left to be interviewed. Wolf clearly tells the team that if they don’t indict by September, it’ll be after November. She clearly says that prosecution decision will be collaborative with DOJ Tax. She clearly says she’s not inclined to toll the 2014 and 2015 tax years ago. In short, she clearly communicates, in July, all the things that the IRS agents claim were surprises in October.

August 5-8, 2022 Exhibit 503: August 5-8, 2022, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler and Lesley Wolf, Subject: Meeting with David. Wolf sets up an August 16 meeting that it appears Ziegler requested, at which only Weiss will be present from DOJ. She requests he run numbers on an early undetermined issue. Ziegler says he’s working with revenue agent — the one Weiss asked to involve in June — on that. Wolf is again warm with Ziegler.

August 11, 2022 Exhibit 501: August 11, 2022, Emails Between Mark Daly, Joseph Ziegler, Christine Puglisi, Michael Dzielak, Michelle Ann Hoffman, Susan Roepcke, cc’ing Jack Morgan, Carly Hudson, and Lesley Wolf, Subject: Meeting. An internal IRS meeting about charging decisions that would precede the meeting with Weiss.

August 12, 2022 Exhibit 502: Calendar Invitation, Subject: Sportsman – Call re Charging, Organized by Mark Daly, Required Attendees: Michael Dzielak, Michelle Ann Hoffman, Susan Roepcke, Jack Morgan, Carly Hudson, Joseph Ziegler, and Christine Puglisi, Scheduled for August 12, 2022. The tax meeting on charging decisions.

August 15-18, 2022 Attachment 4: August 15-18, 2022, Email Between Gary Shapley, Michael Batdorf, and Darrell Waldon, Subject: Sportsman Update. Shapley telling his supervisors that Weiss was still not inclined to charge 2014 and 2015. One of his complaints is that if 2104 and 2015 weren’t charged, it would take the Burisma stuff off the table, which doesn’t sound like a tax decision. He’s still worried about not collecting that revenue, though the revenue is not that much (even if you believe him about what was owed). He claimed that Weiss mocked CT’s non-concurrence, but DOJ Tax does seem to side with not charging some of this. Shapley also claimed that the reason he was only learning venue on CA was through lack of transparency, except that’s totally consistent with what Wolf had said earlier: You decide charges first, then venue.

August 15-18, 2022 Attachment 20: August 15-18, 2022, Emails Between Gary Shapley, Michael Batdorf, and Darrell Waldon, Subject: Sportsman Update. This appears to be a dupe.

August 18, 2022 Exhibit 211: August 18, 2022, Email from Mark Daly to Joseph Ziegler, Michael Dzielak, Michelle Ann Hoffman, Christine Puglisi, Lesley Wolf, and Carly Hudson, cc’ing: Jack Morgan, Jason Poole, and John Kane, Subject: Going forward. At this point, the three remaining interviews were Mesires, Merv[y]n Yan, and James Biden.

August 25, 2022 Attachment 21: August 25, 2022, Emails Between Garret Kerley and Lesley Wolf, cc’ing Joseph Ziegler and Mark Daly, Subject: Case Coordination. The FBI SSA (who may have replaced Joe Gordon) complains they’re not communicating enough between meetings and asks to start an email chain. Wolf asks him to stand down until they can meet — clearly an effort to avoid creating discoverable information. Shapley turns it into a Memo for his files.

September 20 – November 8, 2022 Attachment 29: September 20, 2022, Emails Between Gary Shapley, David Weiss, and Darrell Waldon, Subject: SM Meeting – Management. On September 20, Shapley asks for a quick call. Weiss responds that he would set up a meeting/call for updates in near term (what would end up being the October 7 meeting). Then on November 8, after the prosecution meeting is canceled, Shapley attempts to set up a meeting in December. Shapley then writes back on November 8 saying the FBI can’t make it on December 2, so asks Weiss to confirm that December 5 would work.

September 22, 2022 Attachment 22: Notes from September 22, 2022, 2:30PM, Conversation, at which Lesley Wolf and Mark Daly are Present. Shapley notes that Wolf and Daly both joined late but doesn’t say how late. He describes that the US Attorney (whom he refers to as “her” but has to be a reference to Martin Estrada, who was just confirmed on September 19) has only been sworn in and will need time to get up to speed. DOJ Tax also wanted to defer the charges until after the election. And DE’s finance guy had a number of remaining questions.

September 22, 2022 Attachment 23: September 22, 2022; 3:33PM ff, Email from Gary Shapley to Michael Batdorf, Subject: Conversation with Batdorf Michael T. Shapley texts Batdorf, then emails the texts, complaining about the decision to wait until after the election.

September 22, 2022 Attachment 5: September 22, 2022, 5:28 PM Email from Gary Shapley to Darrell Waldon, Lola Watson, and Michael Batdorf, Subject: SM Update. Shapley tells his supervisors that Wolf said they wouldn’t charge until after the election. Shapley complains that, “the statement is inappropriate let alone the actual action of delaying as a result of the election.” He claims ther are other items (which he doesn’t lay out) “that are equally inappropriate,” probably that they weren’t going to charge the gun charge in October. Shapley was told months ago about this, but is wailing now.

September 22, 2022 Attachment 24: September 22, 2022, Email from Gary Shapley to Michael Batdorf, Darrell Waldon, and Lola Watson, Subject: SM Update. This appears to be a dupe, with the news he had a doctor’s appointment redacted.

September 21-October 6, 2022 Attachment 25: September 21-October 6, 2022, Emails Between Shawn Weede, Ryeshia Holley, and Gary Shapley, cc’ing Garret Kerley and Lesley Wolf, Subject: Call on Charging Timeline. This is a thread between Shawn Weede, Ryeshia Holley (whose name the FBI tried hard to keep obscure), Gary Shapley, about setting up the meeting he wanted. Because he was in the Netherlands the last week of September they instead waited until he returned. Shapley sent out his list of agenda items, showing clearly that he came into the October 7 meeting with an agenda — listing “1. Special counsel 2. election deferral comment – continued delays 3. venue issue”. — and a wildly mistaken understanding of how Special Attorney status works. At 4:34PM, two hours after the WaPo story posted, she says the meeting will include, “Anything further that develops by tomorrow.”

September 21 – October 6, 2022 Attachment 1: September 21-October 6, 2021, Emails Between Shawn Weede, Ryeshia Holley, Gary Shapley, cc’ing Garret Kerley and Lesley Wolf, Subject: Call on 2 Timeline. This shows the last two emails to the earlier thread.

September 28-29, 2022 Exhibit 504: September 29, 2022, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler, Darrell Waldon, and Gary Shapley, cc’ing Lola Watson and Michael Batdorf, Subject: Sportsman. Darrel Waldon writes to note he requested a meeting with the US Attorney’s office. Ziegler notes he’s awaiting information about CDCA’s decision on charging 2017-2019. Hours later, Waldon asks him to call his cell. Seemingly after that call, Ziegler responds that, “we also need to request the presentation of 2014 and 2015 to the criminal chief / US attorney in DC.” This seems to be inconsistent with past claims about when and how closely DC USAO reviewed this case.

September 29, 2022 Exhibit 401: IRS CI Memorandum of Interview with James Biden on September 29, 2022. Ziegler has pointed to this interview — “James B was not sending RHB any deals while he was out in California. … conversations were about getting RHB well at this point and not about business” — as proof that Hunter’s lawyers were lying about his attempts to do business in 2018; yet Hunter’s uncle made clear that he kept trying to engage him and also noted that his memory was not all that clear. The interview also raises questions about Tony Bobulinski’s motives and credibility (as Rob Walker already had). The interview timing is as important as anything else — Shapley went on a tear about the timing of charging before this key interview was even done.

October 6, 2022 Attachment 26: October 6, 2022, Emails Between Gary Shapley, Michael Batdorf, and Darrell Waldon, Subject: Sportsman. After responding to Holley, Shapley alerts his supervisors of the Devlin Barrett story that he would later claim he didn’t know where it was published, noting that it is likely to come up at the meeting the next day. He identifies that the leak was “purportedly from the ‘agent’ level, reveals he spoke with the IRS press person about it, and stated, “I have no additional insight that is anything but a rumor.” This marks the third or fourth inconsistent representation of Shapley’s knowledge of the leak.

October 6, 2022 Exhibit 505: October 6, 2022, Emails Between Joseph Ziegler and Carly Hudson, Subject: Sportsman Uncle question. One of the AUSAs tells Ziegler that Weiss asked about something Ziegler raised, and he states that DOJ-Tax didn’t expect the case to be indicted until 2023, as they were still working on approvals. Hudson sends the email at 10:07AM; Ziegler responds at 6:51PM. I find it exceedingly unlikely Shapley did not also know that the case would not be indicted until 2023.

October 7, 2022: Handwritten notes. As noted these notes show that Shapley misrepresented what David Weiss said and introduced the DC USAO review that would be mooted by the decision not to charge 2014 and 2015, something Shapley had been alerted to months earlier.

October 7-11, 2022: Shapley to Darrell Waldon. The original email Shapley shared, which makes it clear the meeting was dominated by the leak.

October 7-11, 2022 Attachment 6: October 7-11, 2022, Email Between Gary Shapley, Michael Batdorf, and Darrell Waldon, Subject: Sportsman Meeting Update. This adds Mike Batdorf’s response to both Shapley and Waldon, 3 hours after Waldon said he’d handle the referral to TIGTA.

November 7, 2022 Attachment 27: November 7, 2022, Notes, Subject: Telephone Call from FBI Special Agent Mike Dzielak and IRS-CI Case Agent Joe Ziegler. A 10-minute call in which an FBI Special Agent discusses with Shapley and Ziegler that DE USAO was asking for management level emails. Dzielak suggests that the FBI was balking, in the same way that Shapley still was. Shapley offered up that this was proof that DE USAO had no intention of charging, which is utterly debunked by the fact that they had made this request once before (he says in April-May here, but in his House Ways and Means testimony he said it was in March). There’s no mention of the leak.

November 8-10, 2022 Attachment 28: November 8-10, 2022, Emails Between Gary Shapley and Ryeshia Holley, Subject: Next Meeting in Delaware. This reflects Shapley’s immediate effort to schedule a December meeting after the November prosecution meeting was canceled. One reason he did so was because of the request for his own emails.

December 13, 2022: Shapley email to Michael Batdorf. This is the email where Shapley asked Batdorf to ask him if he had any questions about the emails that got turned over.

December 13-16, 2022 Attachment 30: December 13-16, 2022, Emails Between Gary Shapley, Michael Batdorf, and Darrell Waldon, Subject: Meeting at Del USAO Today. Shapley emails Batdorf and Waldon to tell them that prosecutors and the FBI had an all-day meeting in Wilmington. Waldon asks if anyone from Tax participated.

January 6, 2023 Attachment 7: January 6, 2023, Notes, re: Call between Gary Shapley and Michael Batdorf on Whistleblowing. Shapley memorializes an either 8- or 13-minute call with Mike Batdorf, alerting him that on January 4, he lawyered up with “whistleblower” counsel. He gave a weird pitch (including that he would criticize the IRS, but that the IRS could boast that it was an IRS agent who “came forward.” Shapley claimed he would attend to 6103 and 6e matters he has not — including getting approval before sharing. He specifically left out the Senate Finance Committee. And he admitted that he expected DOJ to make “nefarious” allegations against him but hoped the IRS would support him. Batdorf said he hadn’t heard of any allegations.

January 20, 2023 Attachment 8: January 20, 2023, Emails Between Gary Shapley, Michael Batdorf, Darrell Waldon, and Lola Watson, Subject: Discussion – Sportsman. In the guise of finding out what was expected of him, Shapley claimed that FBI investigators had been brought back on the Hunter Biden case (which he learned via Ziegler). He also noted that a third FBI Agent on the team retired before mandatory retirement. Waldon corrects Shapley that the FBI agents met with DE USAO on other issues, but only inquired about Hunter Biden.

January 25-February 10, 2023 Attachment 9: January 25-February 10, 2023, Email Between Gary Shapley and Michael Batdorf, Subject: For Review/Approval: Administrative Leave Request for Protected Whistleblower Activities – Shapley. Shapley asks Batdorf for paid leave for meetings, including with Congress, months before any overt meetings with Congress happened (suggesting he may have met with Grassley). Batdorf not only gives him leave but offers to pick up his work to enable it. Shapley offers to document with whom he was meeting (which given that this request preceded most overt outreach by months, would have been really helpful), but Batdorf says that’s not necessary.

April 13, 2023 Exhibit 212: April 13, 2023, Email from Joseph Ziegler to Lola Watson, cc’ing Gary Shapley, Subject: Sportsman. Ziegler updates Lola Watson (but not Kareem Carter), about meetings Hunter’s lawyers are having, including with Brad Weinsheimer (which leaked). He claims, without evidence, that Weiss was responding to the Merrick Garland testimony. And he addresses two investigations (which involves someone whose taxes would have implications for Hunter Biden — possibly Kevin Morris, would be consistent with Ziegler’s testimony) from which his team has been excluded.

Attachment 31: May 15, 2023, Notes from Conference Call with Kareem Carter, Lola Watson, Gary Shapley, and Joe Ziegler, Re: Sportsman. Memorialization of 17-minute call on which Kareem Carter took the International Tax team off the Hunter Biden case. Some of Shapley’s claims (such as that he documented complaints going back ot June 2020) are not substantiated in the emails released. And he was downright insubordinate on the call. Importantly, his memorialization does not reveal that Ziegler was not invited on the call, and in fact falsely suggests that Ziegler received an invitation to the call.

May 18, 2023 Exhibit 213: May 18, 2023, Email from Joseph Ziegler to Douglas O’Donnell, Daniel Werfel, James Lee, Guy Ficco, Michael Batdorf, Kareem Carter, and Lola Watson, Subject: Sportsman Investigation-Removal of Case Agent. Joseph Ziegler’s email in which he acknowledges breaking chain of command to complain about his removal.