The other day, former FBI Agent Asha Rangappa attributed the 11-year scope of Hunter Biden’s pardon to the possibility that, “For the 1st time, the FBI and Justice Department could literally fabricate evidence, or collaborate with a foreign government to ‘find’ evidence of a ‘crime,’ with zero accountability.”

Rangappa is not wrong that the ability to fabricate evidence to invent new crimes with which to charge Hunter likely helps explain the scope of the pardon.

But her suggestion that a second Trump term would be the “1st time” the FBI was in a position to do that is, itself, a symptom of the “zero accountability” that allowed Trump to win a second term.

FBI and DOJ already allowed various types of people — from spies to grifters to informants to an AUSA — to fabricate evidence against Hunter Biden and his father at least five times, with another four instances of potentially false evidence. It appears that such fabricated evidence played a role in the collapse of Hunter’s plea deal, David Weiss’ request for Special Counsel authority, and the evidence that convicted Hunter in his Delaware trial.

And whatever its influence on Hunter’s ultimate conviction, how Republicans worked to insert fabricated and otherwise suspect information into Hunter’s case is a lesson for how it’ll continue to happen.

The following list includes five examples, with numbered headings, that present compelling evidence of fabricated information used either by Congress or DOJ to go after Hunter and his father, along with four suspect incidents. The first five are presented in order of seriousness with regards to the effect on Hunter’s due process. This post will review each. I’ll do a followup that explains the lessons we can take from this.

- After sharing a debunked Fox News meme, Alexander Smirnov makes false claims of bribery

- Derek Hines narratively plants a crack pipe in Wilmington

- The gun shop also lied on the gun form

- Tony Bobulinski[‘s FBI report] claims he saw a diamond pass hands

- Gal Luft claims Joe Biden met directly with CEFC Chairman Ye in 2016

- FBI enthusiastically welcomes “The Economist’s” claims

- The Scott Brady side channel launders dirt Rudy Giuliani obtained from Russian agents

- FBI makes Peter Schweizer their special Hunter Biden informant

- Judge Maryellen Noreika admits a laptop that has never been indexed

1. After sharing a debunked Fox News meme, Alexander Smirnov makes false claims of bribery

Fabrication: Longtime FBI informant Alexander Smirnov allegedly falsely claimed Mykola Zlochevsky twice told him that he was bribing Joe Biden.

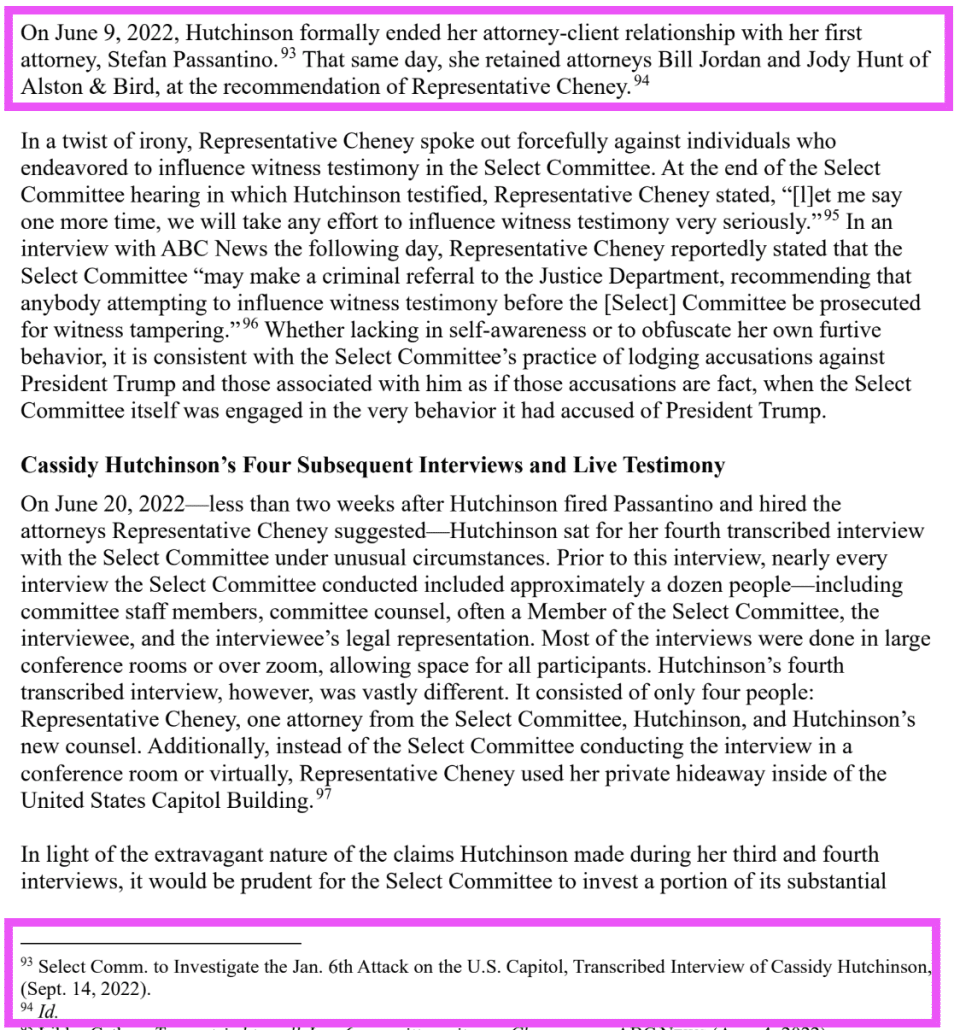

Resolution: According to Scott Brady’s testimony, prosecutor Lesley Wolf had treated the Smirnov allegation with the same skepticism she did other tips shared via the side channel from Rudy. But after Congress leaked the Smirnov FD-1023 and Bill Barr publicly complained that David Weiss was supposed to have investigated it, it appears to have been part of — if not the primary reason — why Weiss reneged on the plea deal with Hunter, obtained Special Counsel status, and ratcheted up charges afterwards.

In January 2020, right in the middle of impeachment, Bill Barr set up a “discreet” side channel overseen via Pittsburgh US Attorney Scott Brady via which Rudy Giuliani could share the dirt on Hunter Biden he had obtained, in part, from known Russian agent, Andrii Derkach.

As part of that process, Brady checked in on all investigations implicated by the side channel: the SDNY investigation into whether Rudy was acting as an unregistered agent of various Ukrainians, David Weiss’ investigation into Hunter Biden, and two oligarchs from whom Rudy solicited dirt on Hunter: Dmitry Firtash and Ihor Kolomoisky. In his interview, Brady didn’t claim to have looked into the investigation into another oligarch from whom Rudy solicited dirt (indirectly): Mykola Zlochevsky. That investigation reportedly started in 2016 while Joe Biden was Vice President and got shut down the previous month, December 2019, right in the middle of an impeachment focused on corruption at Burisma. Rather, Brady dubiously claimed he discovered Smirnov in a search on Hunter and Burisma.

As Alexander Smirnov’s first indictment describes it, it worked the other way. When Smirnov saw a report of Derkach’s meetings with Rudy, Smirnov started texting his handler that, “bribe of [Joe Biden] should soon be in the news))).” He promised to get proof — and then started sending already debunked memes made popular on Fox News.

Neither story convincingly explains how Brady came to reach out to Smirnov to give him opportunity to frame Donald Trump’s opponent. Perhaps one of Smirnov’s three ties to Trump and his people, including the financial ties to Economic Transformation Technologies, which in turn has ties to one of the construction companies that has partnered with Trump Organization in the Middle East, that are the subject of a second indictment against Smirnov, better explains it. That is, perhaps someone in Trump’s camp knew to send him.

Whatever the case, after Brady came calling, Smirnov claimed that at a meeting in 2017, Zlochevsky insinuated he was paying Hunter Biden as protection, from Joe, for himself. Smirnov further claimed that on a phone call the previous year (in 2019, around the time Rudy was expecting a Hunter laptop, and close to the time the investigation into Zlochevsky would be shut down), the Burisma head bragged about hiding his payments so well it would take ten years to find them.

Here was the bribery claim that Trump had first demanded a year earlier from Volodymyr Zelenskyy, all wrapped up with a bow in that Brady side channel!

Brady told Congress his investigators vetted Smirnov’s claims, which was, after all, the purported reason for his side channel. The Smirnov indictment repeatedly described how precisely the thing — Smirnov’s travel records — that Brady claimed he had used to validate Smirnov’s allegations instead debunked them. Jerry Nadler referred Brady for investigation for those false claims to Congress, an investigation that will presumably be killed after inauguration.

On October 23, 2020 — days after Trump personally yelled at Bill Barr about the investigation into Hunter Biden and on the same day that Tony Bobulinski, accompanied by a former Trump White House lawyer, claimed to have personally witnessed a key meeting with CEFC — David Weiss’ team was ordered by Richard Donoghue to receive a briefing on this allegation.

With the personal involvement of Bill Barr, PADAG Richard Donoghue and before him Seth DuCharme, and FBI Deputy Director David Bowdich, Scott Brady found an informant who — if you believe the indictment — was willing to fabricate a bribery claim against Joe and Hunter Biden during an election year.

Don’t tell me that a second Trump administration will only prospectively use fabricated evidence, because it already happened, and the guy currently investigating how it happened was a witness to the process and one of the interviews in this case.

When DOJ ordered prosecutors to accept this alleged fabrication in 2020, AUSA Lesley Wolf reportedly treated it with the same skepticism she treated all the other dirt laundered through the side channel, and it went nowhere. But it didn’t go away. Republicans resuscitated it, in 2023, during their baseless effort to impeach Joe Biden. The FBI tried but failed to limit sharing of Smirnov’s FD-1023. Marjorie Taylor Greene promptly leaked details of it. Bill Barr started making public claims about it in response to Jamie Raskin’s accurate description of what happened in 2020. Then a “whistleblower” leaked the form itself via Chuck Grassley and James Comer. And amid that frenzy, Weiss reneged on his office’s previous assurances that there was no ongoing investigation, told Lindsey Graham that Smirnov’s FD-1023 was part of that ongoing investigation, and then obtained Special Counsel status, out of which the Smirnov false statements prosecution arose.

Yes, after the Smirnov allegation served as a precipitating factor in the collapse of Hunter Biden’s plea deal, he too is now being prosecuted. But by all appearances, the fabrication and the way Republicans leveraged it nevertheless played a central role in the plight of Hunter Biden, a central role in prosecuting him with far more serious charges than originally planned. The fabrication had its effect, and the effect was to make Hunter a felon.

Update: On December 10, Alexander Smirnov signed a plea deal admitting his bribery claims against Joe Biden were fabricated.

The events Defendant first reported to the Handler in June 2020 were fabrications. In truth and fact. Defendant had contact with executives from Burisma in 2017, after the end of the Obama-Biden Administration and after the then-Ukrainian Prosecutor General had been fired in February 2016 — in other words, when Public Official 1 could not engage in any official act to influence U.S. policy and when the Prosecutor General was no longer in office. Defendant transformed his routine and unextraordinary business contacts with Burisma in 2017 and later into bribery allegations against Public Official 1, the presumptive nominee of one of the two major political parties for President, after expressing bias against Public Official 1 and his candidacy.

2. Derek Hines narratively plants a crack pipe in Wilmington

Fabrication: AUSA Derek Hines repeatedly claimed that a line from Hunter Biden’s memoir set in February to March 2019 in New Haven happened in 2018 in Wilmington.

Resolution: None. Hines presented a version of this claim to jurors.

Prosecutors faced a number of challenges with charging Hunter Biden for the gun crime David Weiss had earlier decided to divert. They needed to defend against a vindictive prosecution claim that they had ratcheted up the gun charges against Hunter Biden because he didn’t accept the narrowed plea agreement after Weiss reneged on his June 19, 2023 assurances there was no ongoing investigation. Their plight was made worse because investigators had never taken the most basic investigative steps to pursue the gun charge: they had never obtained a warrant to search Hunter’s digital evidence for proof he was addicted when he owned the gun, and they had never done laboratory analysis on the pouch in which the gun was found. They did both those things after indicting Hunter for the gun crimes in 2023, after the statute of limitations had already expired.

The decision to charge Hunter with the gun crimes appears to have amounted to, “We know Hunter was an addict based on stuff obtained on the laptop and published in the right wing press” (indeed, one of Judge Maryellen Noreika’s decisions mistook stuff published by Murdoch rags for evidence before her).

Abbe Lowell has claimed that, at least in August 2023, prosecutors told him they had no need to rely on the laptop for evidence at trial. Prosecutors seem to have believed, incorrectly, that the laptop was an exact match of Hunter Biden’s iCloud. They similarly seem to have believed that Hunter’s memoir provided adequate proof that Hunter was doing drugs during the 11-day period in October 2018 he owned the gun. In fact, the memoir says almost nothing about that period.

Nevertheless, AUSA Derek Hines made a version of that argument — that the memoir reflected drug use during or closely after the period he owned the gun — over and over, at least seven times by my last count. Hines did so by claiming that his favorite line from the memoir — “It was me and a crack pipe in a Super 8, not knowing which the fuck way was up” — took place in fall 2018 in Wilmington, DE, and not in Hunter’s stopover in New Haven between the time he left Keith Ablow’s treatment in February 2019 and arrived back in Wilmington, before then moving back to Los Angeles permanently.

He simply moved the narrative reference to the crack pipe in a Super 8 from one crime scene to the one where he needed it to be, from 2019 to 2018, from New Haven to Wilmington. Just like a dirty cop moves an actual crack pipe from one location to another.

(This post includes the full memoir excerpt and a summary of Hunter’s spending around New Haven; it also notes that the claim he was staying in Super 8s was, as so much auto-biography is, embellishment.) The argument was absolutely crucial to Hines’ responses to Hunter’s selective and vindictive prosecution claims, falsely substantiating a defense of the prosecutorial decision to charge Hunter with the gun crimes (and even the tax crimes) because there was so much evidence against Hunter in the memoir, when in fact the memoir had a gap for the crucial period.

Hines sustained this fabrication with the jury by selectively presenting the memoir to exclude the discussion of leaving Ablow’s treatment and the way it exacerbated Hunter’s addiction. And when he walked his summary witness through the memoir, he again falsely insinuated that the line took place in 2018, not 2019.

Q. And how about any section in Chapter 9 or Chapter 10, the relevant time period for 2018?

A. No.

Q. And finally, page 208, continuing in the same chapter, after Mr. Biden describes full blown addiction, Exhibit 19, page 208, does Mr. Biden write “crack is a great leveler.” And then he goes on to say “just like in California.” Is that what he goes on to say here?

A. Yes.

Q. If you zoom out, above that, does he say in the first paragraph, “It was me and a crack pipe and a super eight, not knowing which the fuck way was up.” Are those his words?

A. Yes.

Q. And this is in the same chapter when he describes his return in the fall of 2018; correct?

To be sure: Hunter was also staying in cheap motels while he was in Wilmington in 2018, including the night before Hallie Biden found the gun. But those stays don’t appear in his memoir, and so prosecutors had little to no evidence that he was smoking a crack pipe while staying there. As noted, virtually nothing from those weeks in Wilmington appears in his memoir.

But that was true of the evidence against Hunter generally. While there was a great deal of evidence showing Hunter using drugs before and after the period he owned the gun, there was little definitive evidence showing him using in those 11 days.

Prosecutors charged a case for which they had very little direct evidence of drug use during the period in question. One way they won a conviction anyway was by misrepresenting the timing and location of this line in the memoir.

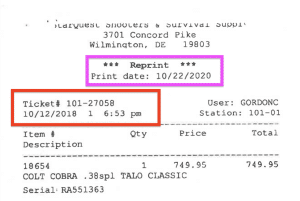

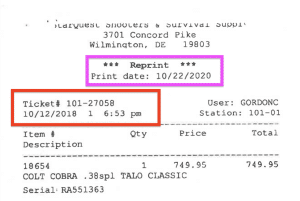

3. The gun shop also lied on the gun form

Fabrication: Sometime after reporting the gun purchase, the gun shop added a claim to the original form that they had asked Hunter for a second form of ID, in addition to his passport (which, because it lacks an address, would not suffice).

Resolution: Judge Noreika prevented Hunter from presenting the doctored form to the jury or questioning specifically on the question (though Abbe Lowell did elicit closely related answers), thereby preventing Hunter from discrediting the gun shop practices generally or the proving Hunter’s lie on the gun form was not material.

According to a contested Abbe Lowell filing, before the election in 2020, the guy who owned the gun shop from which Hunter bought a gun, Ron Palimere, and the State Trooper who first investigated the gun in 2018, Vincent Clemons, exchanged WhatsApp texts about how they could release the paperwork tied to the gun purchase in order to help beat Joe Biden.

[Vincent] Clemons was the Delaware State Police officer who first arrived at Janssens’ grocery store on October 23, 2018 when Hallie Biden threw a bag containing the handgun into a trash can in front of the store. It was Clemons who took statements about the handgun from both Hallie and Hunter Biden and was part of filling out an official police report on the issue. Two years later, he is in the communications with [Ron] Palimere about the Form 4473, one of which states: “Yep your side is simple – Hunter bought a gun from you, he filled out the proper forms and the Feds approved him for a purchase.” (emphasis added). Palimere later responded, “I’ll keep it short and sweet as well: Hunter bought a gun. The police visited me asking for verification of the purchase and that’s all I can recall from that day. It was over 2 years ago.” (TAB 6B, 10/26/20 Palimere-Clemons Texts at 4, 6.) The reference to filling out the “proper forms” is not lost on defense counsel given what transpired thereafter. And, despite the importance of Clemons (e.g., the person who actually took the statements), the Special Counsel is foregoing him as a witness to call two other Delaware officers instead.

As part of their effort to use Hunter’s gun purchase to hurt his father in the 2020 election, it appears that on October 22, 2020 they for the first time printed out the receipt recording Hunter’s purchase of the gun.

They would leak these materials, as well as the partisan write-up of the investigation penned after the fact by Clemons, to right wing propagandists.

Their reference to “proper forms” was important, Lowell argued, because some time after the original gun form was emailed to ATF after the gun had already been lost and recovered, it got altered, to falsely reflect that the gun shop obtained a second form of ID before selling a guy they knew to be Joe Biden’s kid a gun. (There’s no way this vehicle registration could have served as a second ID to supplement the passport, because Hunter was driving his father’s Cadillac, and so the registration would have been in Dad’s name.)

Hunter got evidence that these key witnesses tried to use these documents as part of a political hit job long after his selective and vindictive prosecution bids were rejected. And Judge Maryellen Noreika prohibited Hunter’s team from introducing either that the gun shop owner hated Joe Biden and also wanted to get Hunter out of his shop as quickly as possible and as a result sold him a gun without first getting the proper paperwork, or that they altered the form after the fact. Jurors were left with no explanation of why gun shop employee Jason Turner repeatedly claimed to have written “DE Vehicle Registration” on the form, but it didn’t appear on the form before them (see this post for more on the way the gun shop employees’ testimony materially conflicted).

The means by which prosecutors managed to cover up that the gun shop had also broken the law is fairly banal: They relied on secondary witnesses for key testimony rather than that of people more directly implicated in similar conduct as Hunter (the gun shop owner was immunized to sustain this case), and performed ignorance of details about this corruption at trial.

That happens all the time in criminal trials prosecuted by AUSAs who excel at prosecutorial dickishness. Judge Noreika’s decision to exclude a doctored gun form (and instead rely on a scan at trial) might have been a ripe issue for appeal. Certainly, by excluding evidence that the gun sale went through without proper paperwork, she excluded evidence that Hunter’s lie was not material.

But the larger issue is that Hunter Biden was prosecuted for lying on a gun form even while prosecutors covered up that the gun shop owner himself had an employee fabricate the form after the fact, possibly to hide his own role in leaking to the press and trying to push such a case against Joe Biden’s kid.

4. Tony Bobulinski[‘s FBI report] claims he saw a diamond pass hands

Fabrication: After Trump hosted Tony Bobulinski at a debate, the FBI recorded claims that Bobulinski personally witnessed a key CEFC meeting.

Resolution: After prosecutors deemed Bobulinski’s testimony unreliable and so avoided follow-up, IRS agents claimed prosecutors improperly withheld Bobulinski’s testimony, leading to his platforming of slightly different claims in a hearing purporting to support impeachment. Bobulinski accused FBI of misrecording his interview.

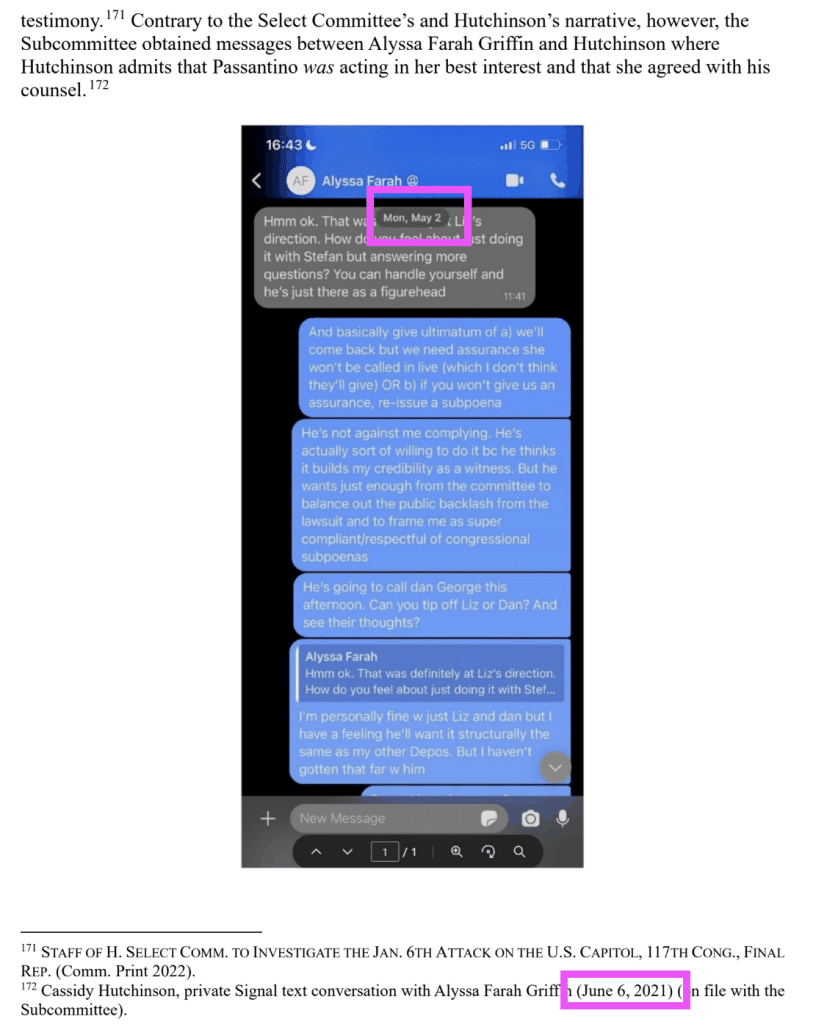

The day after being hosted by Donald Trump at one of the Presidential debates, Tony Bobulinski — represented by onetime White House Counsel and future January 6 witness attorney Stefan Passantino — went to the FBI and made certain claims about Hunter Biden’s ties to CEFC. Among other things, he claimed that he participated in a Miami meeting between Hunter Biden and CEFC Chairman Ye Jianming.

BOBULINSKI first met in person with members of the BIDEN family at a 2017 meeting in Miami, Florida. BOBULINSKI, GILLIAR, WALKER, HUNTER BIDEN, and YE all attended the meeting. Also in attendance was Director JIAN ZANG (“ZANG”), a CEFC Director involved in forming new businesses and capitalizing them at the request of CEFC. At the meeting, BOBULINSKI witnessed a large diamond gemstone given as a gift to HUNTER BIDEN by YE.

The work conducted by CEFC, GILLIAR, WALKER, HUNTER BIDEN, JAMES BIDEN and YE over the preceding two years was discussed in detail at the Miami meeting. In particular, CEFC was closing significant investment deals in Poland, Kazakhstan, Romania, Oman, and the Middle East during this period of time. CEFC had used its relationship with HUNTER BIDEN and JAMES BIDEN – and the influence attached to the BIDEN name – to advance CEFC’s interests abroad. HUNTER BIDEN and JAMES BIDEN did not receive any monetary compensation for their assistance in these projects. HUNTER BIDEN and JAMES BIDEN did not receive any compensation because JOSEPH BIDEN was still VPOTUS during this time period.

He also claimed that when he met Joe Biden in May 2017, they discussed the business deal.

Further, BOBULINSKI met with JOSEPH BIDEN in person on May 2, 2017 at approximately 10:30 PM at the Beverly Hills Hilton Hotel bar in Beverly Hills, California where they discussed SINOHAWK

In his congressional testimony, Bobulinski disclaimed several things recorded in his FBI interview report. He said he did not attend the meeting in Miami nor witnessed the transfer of a diamond to Hunter. He backed off his description of the substance of his meetings with Biden.

Not only did Joe Biden meet with me twice for an extensive amount of time — and we weren’t talking about the weather or niceties. We had an extensive discussion about his family, my family, my business career, where I was successful, the military background, and what I was doing with the Chinese. However, coached before that meeting to not go into a lot of detail by Hunter and Jim Biden. Okay?

The effect here is subtle. Bobulinski — who is furious that Hunter cut him out of this deal — is still trying to put Joe Biden at the center of it, he’s still trying to claim (contracts and finances notwithstanding) that the aspiring President got 10% of the deal. That’s the now partly-disclaimed story he told, allegedly presenting himself as a direct witness to more than he was, when he waltzed into the FBI fresh off his campaign event with Donald Trump.

5. Gal Luft claims Joe Biden met directly with CEFC Chairman Ye in 2016

Fabrication: Uncorroborated testimony that Hunter’s financial payments from CEFC started while Joe Biden was still Vice President.

Resolution: Public release of charges after Luft got House Republicans to claim a cover-up.

At a time when he would have known he was under investigation for his role in Patrick Ho’s influence-peddling scheme, March 2019 (for which he was charged and currently awaits extradition), Gal Luft met with investigators in Belgium for two interviews, one focusing on his role in Ho’s activities, another focused on Hunter Biden. At the latter, he claimed that Joe Biden had met with Ye when he was still President, in 2016, and Hunter had gotten paid in 2016 too.

LUFT is aware that YE met with BIDEN and HUNTER at the end of 2016 at the Four Seasons Hotel in Washington.

The meeting at which Biden was present was later, in March 2017. Here’s how Rob Walker described it.

Walker: It was out‐of‐office. Ah, we were in ah.., D. C. at the Four Seasons…

Soline: Hmph hmph. Walker: …and ah.., we were having lunch and he.., he stopped in…

Soline: Hmph hmph.

Walker: …then he’d ah, leave.

Wilson: Okay.

Walker: That was it.

Wilson: Just said hello to everybody and then…

Walker: Yes.

Wilson: …took off?

Walker: He literally sat down. I don’t even think he drank water. I think Hunter said um.., I may be tryin’ to start a company, ah, or tried to do something with these guys and could you.., and think he was like “if I’m around”….and he’d show up.

So, too, was a $3 million payment that Luft said Hunter (actually, Rob Walker) received. Luft said it was paid in December 2016; it was paid in March 2017.

At the meeting, Luft “was directly asked to identify his CEFC CHINA ENERGY source(s) but refused to do so.”

Here’s how the tax indictment against Hunter (though not dissimilar to Bobulinski’s claims) described these ties.

8. In the late fall of 2015, the Defendant, Business Associate 1, and Business Associate 2 began to investigate potential infrastructure projects with individuals associated with CEFC China Energy Co Ltd. (CEFC), a Chinese energy conglomerate.

9. In or around December of that year, the Defendant met in Washington, D.C., with individuals associated with CEFC. During the next two years the Defendant, Business Associate 1, and Business Associate 2 continued to meet with individuals associated with CEFC, including in February 2017, with CEFC’s then-Chairman (hereafter “the Chairman”).

10. On or about March 1, 2017, State Energy HK, a Hong Kong entity associated with CEFC, paid approximately $3 million to Business Associate 1’s entity for sourcing deals and for identifying other potential ventures. The Defendant had an oral agreement with Business Associate 1 to receive one-third of those funds, or a million dollars. The Defendant, in turn, directed a portion of those million dollars to Business Associate 3.

On these topics, Luft’s testimony is subtle — just a temporal shift by a few months to make the sleazy Biden relationship with CEFC more damning (and put FARA charges that SDNY seems to have declined by the time Luft went public in 2022 back on the table). Perhaps unsurprisingly, Luft slightly adjusted his claims about his testimony when he went to NYPost after his arrest, correcting the monetary amounts and timing focusing instead on the later event at which Biden was co-present with Ye.

Luft’s comments about Hunter Biden don’t appear in his own indictment. And indeed, there’s no evidence he wittingly lied himself; whereas Bobulinski had claimed firsthand knowledge of the Miami meeting, Luft was only claiming to have second-hand knowledge of this information. It could well have been an effort from his own sources to harm the Bidens. In his effort to allegedly disavow his own involvement in this influence peddling, Luft certainly had cause to want to shift CEFC’s attempt to recruit James Woolsey, likely sparked by Trump’s election win, to instead focus on what was surely a similar attempt to cultivate the Biden family, something that had less value after Trump’s win.

The files released by the disgruntled IRS agents show that by 2021, SDNY was no longer pursuing a FARA investigation against the Bidens with relation to CEFC, so whatever Luft claim, it has not (at least thus far) done lasting damage, which is the way investigations are supposed to work.

FBI enthusiastically welcomes “The Economist’s” claims

There are a range of Ukrainians who shared dirt on Hunter Biden that made it to investigators. The first two of those, by chronology, were Ukrainians who were briefly made informants by people in Los Angeles, but who were subsequently deemed to be part of an influence operation targeting Joe Biden.

As Johnathan Buma described it, the thumb drive Ukrainians he called Rollie and the Economist provided targeting Hunter Biden in early 2019 (which would have been almost immediately after the investigation into Hunter was opened in Delaware) largely focused on the sex and drugs that reflect Hunter’s addiction, as well as financial improprieties.

After receiving the presentation from ROLLIE and THE ECONOMIST, THE ECONOMIST provided me a thumb drive with some supporting documentation, much of which was in the Ukrainian language, which I do not speak. After I submitted my FD-1023 reports on this information, I was put in touch with two agents working out of the Baltimore office on a case based in Delaware involving Hunter. spoke on the phone with these agents, who were very interested in the information due to its relation to their ongoing investigation that was mostly involving allegations of Hunter’s involvement with drugs and prostitution. Information derived from ROLLIE and THE ECONOMIST had previously been found to be credible, so this was handled carefully and quickly transferred over to the agents in Baltimore and was serilized in their case file. While I transferred the information, I could not read the Ukrainian language, and it required translation in order to determine the viability of the electronic document’s presumed support of the allegations related to Hunter and Burisma, which were presented and summarized in a PowerPoint presentation created by THE ECONOMIST and serialized in the case file. I had no involvement in the subsequent investigation concerning Burisma and the Bidens and never received any update from these agents as to whether the information was corroborated, but later learned from the media that some of the allegations appeared to have been true. Based on the level of corruption and the RIS’ past usage of Ukraine for influence operations raw single-source information derived from Ukraine is always viewed with skepticism by members of the USIC with some specialty and experience in Ukrainian matters.

Buma went on to describe how, when he shared information about Rudy’s ties to Russian spies, his supervisor shut him down.

I’ve written why I am skeptical of Buma. It’s also worth noting that, in fact, in spite of four years of investigation, the FBI never managed to substantiate what he seems to suggest the claims were, so he’s likely wrong that the tips from Rollie and the Economist held up to scrutiny.

Given that, per Buma’s description, these two were quickly disqualified as informants, it seems likely that their information was deemed problematic. That is, it seems likely that this information was vetted and found wanting, which is (again, like the Luft allegations) precisely what is supposed to happen with potentially motivated informant information.

The Scott Brady side channel launders dirt Rudy Giuliani obtained from Russian agents

It’s what DOJ did with Rudy Giuliani’s information, obtained in part from known Russian agents trying to interfere in the election, that defies excuse.

By setting up the Brady Side channel (and related steps), Barr thwarted the SDNY investigation into whether Rudy was himself an unregistered agent of Ukrainian sources. SDNY did not then — and it appears, did not ever — get access to the interview Brady did with Trump’s personal lawyer about how he collected this information. And Brady attempted to intervene in the SDNY investigation to tell them they had gotten it wrong.

As noted above, at Barr’s direction, Brady also created a way that Smirnov could fabricate an allegedly false bribery claim against Joe Biden. He created a way to, effectively, spy on several ongoing investigations.

And, while his sole purpose was supposed to be vetting, his vetting process appears to have done nothing more than serve as a laundry service, insulating Rudy and his sources from investigators and parachuting his information in with the sanction of top DOJ personnel, as when Richard Donoghue ordered DE USAO to provide information about their investigation and accept information in exchange, into the Hunter investigation.

Q And did your AUSAs ever communicate to you issues they were having with Ms. Wolf?

A Not with Ms. Wolf specifically — well, no strike that.

There was an occasion with Ms. Wolf as well, but they would communicate to me the issues that we were having, our investigative team was having with both the FBI and with Delaware and with SDNY. Really the only office we didn’t have any issues with was EDNY. It was Rich Donoghue’s office.

Q Okay.

And so, before you communicated with the PADAG that you needed assistance, did you have an initiative to talk with Mr. Weiss?

A Yeah, I wouldn’t always run to the principal right away, right. I would try to go professional to professional, you know, U.S. attorney to U.S. attorney, and we would try to resolve things. And, only when we couldn’t, would we elevate it to the DAG’s office and involve the PADAG.

Mr. Rosen was never involved directly in our communications. It was always the PADAG.

Q Okay.

And what feedback was Mr. Weiss giving you during that time period before you had to involve the PADAG?

Mr. Lelling. Only in general terms.

Mr. Brady. Usually Mr. Weiss was in receiving mode and would say that he would talk to his team to try to resolve it?

Q At any point did you have to advise Mr. Weiss that you’ve been, you know, you’ve been charged by the DAG to collect this information, and part of your charge and your duty, and correct me if I’m wrong, is to analyze it and hand it off?

A That’s correct and to coordinate with other offices. And, yes, I reminded Mr. Weiss of that obligation that we have, of that requirement, and the FBI on a regular basis as well.

[snip]

Q And were you ever told that the Delaware U.S. Attorney’s Office did not want a briefing from your office?

A I believe I was. I don’t remember. But I know that we had trouble scheduling it.

Q Okay. And then, further down, it states AUSA Wolf’s comments made clear she did not want to cooperate with the Pittsburgh USAO, and that she had already concluded no information from that office could be credible stating her belief that it all came from Rudy Giuliani.

Were you ever made aware of Ms. Wolf’s processing and decisions regarding this briefing, and why she didn’t want the briefing?

A I was not. We did, however, make it clear that some of the information including this 1023 did not come from Mr. Giuliani.

We do not know what kind of information got laundered through this process. We do know that after four years of investigation, DE USAO did not charge any of the allegations that Rudy’s Russian spy buddies were pushing. Again, it looks like prosecutors in Delaware properly viewed this information with skepticism.

FBI makes Peter Schweizer their special Hunter Biden informant

But the import of that process shares a feature with another of the efforts to launder dirt into an investigation into Hunter Biden.

By 2020, even as Arkansas’ US Attorney’s Office was four years into an investigation of the Clinton Foundation predicated in three different venues at least partly on Peter Schweizer’s Clinton Cash, some FBI agents in DC had not just used his writing, but made him a formal informant to report on Hunter Biden. It seems that Schweizer was at least partly repackaging allegations based on the laptop, because (according to testimony from retired FBI agent Tim Thibault), when FBI agents from Delaware asked to stop getting the information, they effectively said they already had it.

At the request of the Delaware investigators, Thibault shut down Schweizer as an informant, four years after Thibault had been one of the the three FBI agents who had chased the Clinton Foundation allegations based on Schweizer’s work.

But like the Brady Side channel, this privileged means of sharing dirt — of uncertain quality — on Hunter Biden became a means to discipline those who tried to protect the integrity of investigations by limiting the partisan shit dumped into them. As Lesley Wolf also did, Thibault faced an entire campaign of retaliation (including from two agents who were themselves firebreathing partisans, who claimed that Thibault shut good work down), including public humiliation in an oversight hearing with Chris Wray.

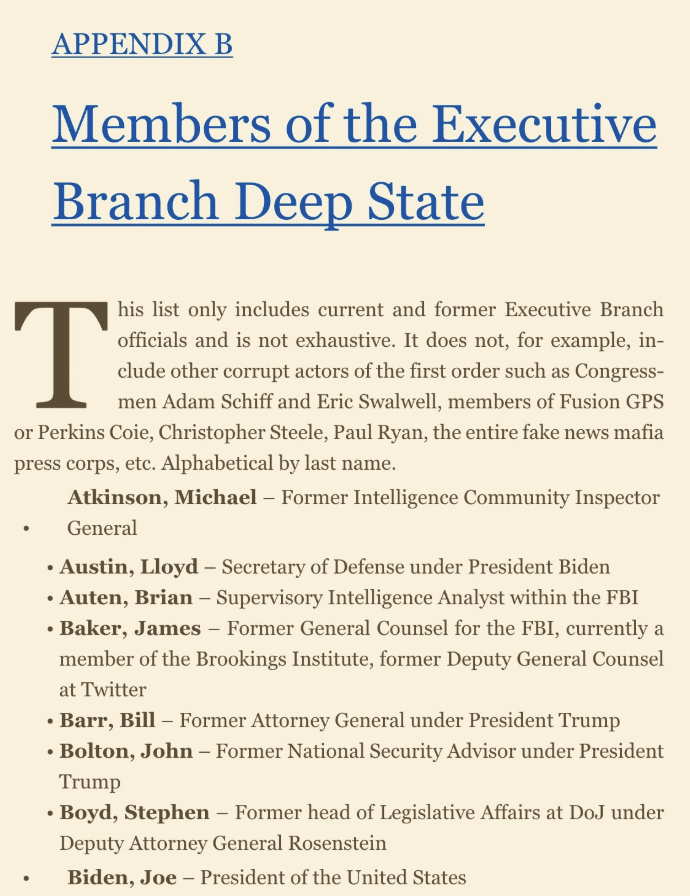

The threats that Wolf faced may have been worse than what Thibault faced. But unlike Wolf, Thibault is on the (dated) Kash Patel’s enemies list.

We don’t know what substance of information Schweizer share with the FBI; we know the investigative agents didn’t want it, at least in that form.

But a more important point is that Thibault’s efforts (at the request of the investigative team itself) to protect the investigation from partisan taint, just like Wolf’s, made him a target for professional and potentially dangerous retaliation.

Judge Maryellen Noreika admits a laptop that has never been indexed

Which brings us, of course, to the laptop (and accompanying hard drive, purportedly a copy of the laptop but the Cellebrite report from which was 62% longer).

There are a great deal of reasons to be skeptical about the laptop: the discrepancies between John Paul Mac Isaac’s story and the FBI’s, JPMI’s claim that the FBI tried to boot it up four days before the known warrant, the possibility that Bill Barr got sent a copy.

But the biggest caution has to do with its handling.

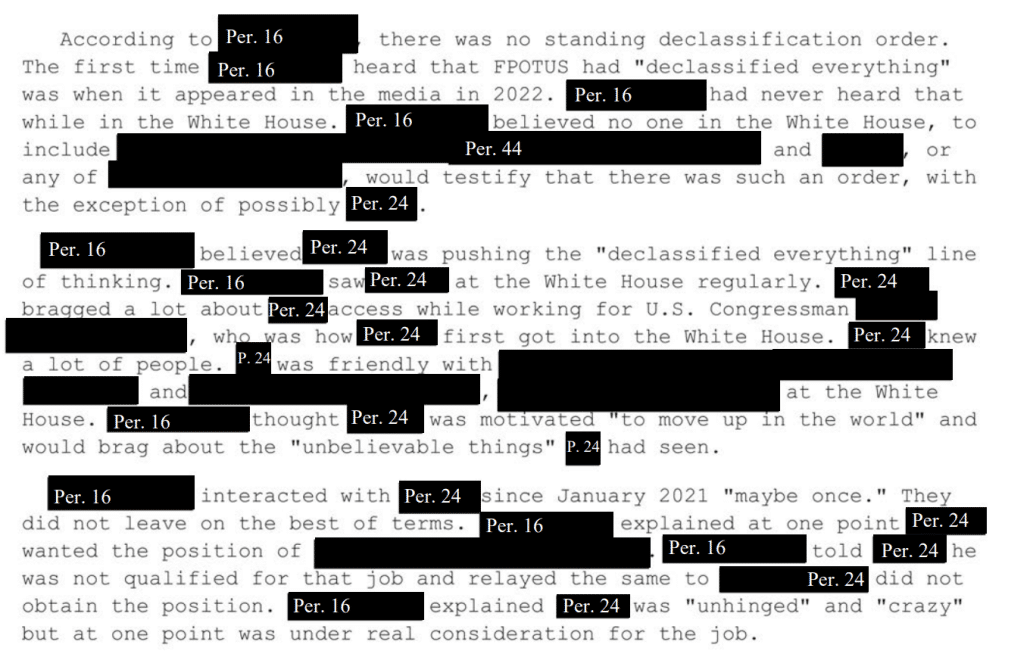

Immediately after the release by NYPost, Rudy ran his yap and said it didn’t really matter if Derkach was a Russian spy and that he regarded the hard drive copy of the laptop he had to be an “extension” of his efforts to collect dirt from Russian spies. (In congressional testimony, Scott Brady admitted that Rudy never told him about the laptop.)

Thanks to Gary Shapley, we know the panicked meeting that ensued, as the investigative team tried to justify the year that they had spent snooping in a laptop that might have, after all, had something to do with Russia’s information operation. And Shapley recorded in real time not just that prosecutors had an email, dated March 31, 2020, recording some kind of concerns “about quality and completeness of imaged/recovered information from the hard drive,” but that they would not share it with anyone who might have to testify at trial. He also described that, at the time of that October 22, 2020 meeting, the FBI had never checked when the files on the laptop got added when. They had never checked to see if someone had packaged Joe Biden’s son’s digital life up onto a laptop to be dealt to the FBI.

My suspicion is that, after that time, prosecutors decided they shouldn’t try to introduce the laptop at any trial, because they could never clean it of this stench (they don’t appear to have considered investigating that stench, which continues to baffle me to this day). But after brashly telling Abbe Lowell in August 2023 they didn’t need no fucking laptop to charge the gun case, a different set of prosecutors discovered they had almost no evidence showing that Hunter Biden was doing drugs in the 11 days he owned a gun. They discovered that the all-critical communications between Hunter and Hallie Biden from that period — saved from a phone he used until replacement phones for ones he lost days before he bought the gun arrived during this same period — existed only on that laptop which he did not yet possess.

And rather than going back and pretending they were the FBI, acting like the FBI — rather than going back and doing the index that would tell them whether the laptop really did reflect Hunter’s use of it or someone else packaging up the digital life of the then President’s son — they instead bulldozed through things like the dickish prosecutors they are.

They never indexed the laptop. Never.

They never Bates stamped their own exhibits.

They never provided the laptop in e-discovery format.

In fact, after Hunter’s team did their own extraction so they could do searches, prosecutors raised questions about the integrity of their own source, the laptop.

When Judge Noreika denied my request for the extraction reports that Derek Hines claimed authenticated the laptop, she admitted that she had never required a report that actually referred to the laptop by some kind of identifier. The laptop evidence came in with no formal validation whatsoever.

The only two pieces of authentication used to validate the laptop at trial were the fact it had accessed Hunter’s iCloud account (but Zoe Kestan testified at trial that so had her own laptop), and that JPMI had sent an invoice to Hunter’s public iCloud email.

That was it.

The laptop and the most damning evidence against Hunter all came in without the most basic kind of validation. And as a result, we still can’t say with certainty we know fuckall about its provenance. Nor can we say whether its existence as a collection of evidence was doctored by hostile players (who would just as likely be Republican rat-fuckers as Russian spies).

We simply don’t know, and anyone claiming they do, is lying or withholding reporting and testimony that could have come in as part of the trial.

So we still can’t say whether the most famous prop in this whole story involved fabrications or manipulations or merely the disordered digital life of a hopelessly addicted man.

Hunter has been pardoned from these convictions (though James Comer has promised to continue hounding him going forward). Even still, these nine instances of dodgy evidence used against the President’s son provide lessons — none pretty — about what we should expect going forward.