Amy Gleason’s Four — I Mean Five — Executive Orders

In both her March 14 and March 19 declarations submitted in the CREW FOIA case [docket], purported DOGE Administrator Amy Gleason described that DOGE’s job was — in addition to the technology modernization function the original USDS was tasked with — to advance President Trump’s 18-month “DOGE agenda.”

19. As described in the USDS Order, USDS is charged with furthering President’s Trump DOGE agenda, by “modernizing Federal technology and software to maximize governmental efficiency and productivity.”

20. In furtherance of these efforts, the USDS Order directs the USDS Administrator to work with agency heads to “promote inter-operability between agency networks and systems, ensure data integrity, and facilitate responsible data collection and synchronization.”

21. In addition, the USDS Order charges the DOGE Service Temporary Organization with advancing President Trump’s 18 month “DOGE agenda,” as set forth in various Executive Orders. See ¶¶ 7, 24.

She describes the “DOGE agenda,” which she says stems from four Executive Orders and one Presidential Memorandum, this way:

24. The “DOGE agenda” includes the technology modernization efforts described in the USDS Order, as well as initiatives that are described in four separate Executive Orders and a presidential memorandum. These materials describe distinct—and limited—roles for USDS and agency heads and agency DOGE Teams. They include:

a. Executive Order 14,170, Reforming the Federal Hiring Process and Restoring Merit to Government Service (Jan. 20, 2025), which directs the USDS Administrator to consult with the Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy and the OMB Director on a federal hiring plan that focuses on hiring highly skilled Americans. The order charges the Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy with actually developing the plan and disseminating it to agency heads.

b. Presidential Memorandum, Hiring Freeze (Jan. 20, 2025), which instructs the USDS Administrator to consult with the OMB Director, who is responsible for submitting a “plan to reduce the size of the Federal Government’s workforce through efficiency improvements and attrition.” The USDS Administrator is also responsible for consulting with the OMB Director and the Treasury Secretary, who is responsible for determining when to lift the hiring freeze at the Internal Revenue Service.

c. Executive Order 14,210, Implementing the President’s “Department of Government Efficiency” Workforce Optimization (Feb. 11, 2025), which directs agency heads to reduce agency headcount and agency DOGE Team Leads to provide monthly reports to the USDS Administrator on agency hiring. The USDS Administrator is also directed to report to the President on agencies’ compliance with the order.

d. Executive Order 14,218, Ending Taxpayer Subsidization of Open Borders (Feb. 19, 2025), which requires the USDS Administrator to consult with the Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy and the OMB Director to identify sources of federal funding for illegal immigrants and collectively recommend agency actions to align spending with the purposes of the order and, where relevant, enhance eligibility verification systems.

e. Executive Order 14,219, Ensuring Lawful Governance and Implementing the President’s “Department of Government Efficiency” Deregulatory Initiative (Feb. 19, 2025), which requires agency heads, in consultation with their DOGE Teams Leads, to undertake deregulatory efforts.

f. Executive Order, 14,222, Implementing the President’s “Department of Government Efficiency” Cost Efficiency Initiative, (Feb. 26, 2025), which requires each agency head to make federal expenditures transparent and for DOGE Team Leads to report to the USDS Administrator on contracting and non-essential travel expenses.

25. Cumulatively, these orders and memorandum set forth the responsibilities assigned to USDS, the U.S. DOGE Service Temporary Organization, agency DOGE Teams, and agency DOGE Team Leads. As an entity created by Executive Order, USDS has no other independent sources of legal authority. [emphasis and links added]

There’s a lot that’s interesting about this — not least that she described the DOGE agenda consisted of four EOs but she cites five.

So much for government efficiency.

My guess is EO 14,218, which assigns DOGE the role of hunting down payments that go to undocumented people, was added as an afterthought. The EO does provide DOGE a role, but (unlike most of the others) does not address DOGE in the title.

What I’m particularly interested in, though, is that Gleason does not include EO 14,217, Commencing the Reduction of teh Federal Bureaucracy, the February 19 EO that ordered Institute for Peace, among other entities, to be shut down.

That’s not surprising. DOGE isn’t mentioned in the EO at all.

But that’s interesting because, according to USIP’s complaint, at a time when George Moose was still unquestionably President of the Institute for Peace, starting the day after the EO on February 20, DOGE representatives started nagging Moose about shutting down. First, Chris Young reached out. Then Moose met with DOGE representatives as President of USIP. Then Moose sent a letter to OMB, consistent with instructions in the EO. Then DOGE started conducting reconnaissance in advance of shutting USIP down.

39. On February 20, 2025, the day after the Executive Order was issued, Chris Young, a representative of the U.S. DOGE Service, contacted the Institute.

40. The Institute agreed to hold a virtual meeting with DOGE representatives on February 24, 2025. Ex. A, Declaration of George Moose; Ex. D, Declaration of George Foote.

41. In that February 24 meeting, the Institute president, Mr. Moose, and outside counsel for the Institute, George Foote, explained to DOGE representatives Cavanaugh, Burnham, and Altik that the Institute is an independent nonprofit corporation outside of the Executive branch. ; Ex. A, Declaration of George Moose; Ex. D, Declaration of George Foote.

42. On March 5, 2025, the Institute submitted a courtesy letter to OMB responding to the requests made in the Executive Order. The letter explained the Institute’s establishment by Congress and its status as an independent nonprofit that is not an Executive branch entity and reiterated the Institute’s willingness to maintain its longstanding cooperation with the Executive branch with regard to the foreign policy agenda of the President of the United States. Ex. D [sic], OMB Letter.

43. On or about March 8, 2025, Mr. Moose received word that DOGE was making inquiries into the status of the Institute’s security operations. These inquiries were intended to facilitate DOGE’s access to the Institute’s headquarters, just as DOGE had done with respect to numerous executive agencies. Ex. A, Declaration of George Moose.

44. On or about March 9, 2025, USIP outside counsel George Foote emailed Defendants Burnham, Altik, and Cavanaugh with information about the non-federal nature of the Institute’s security and the Institute’s ownership of its headquarters building. Mr. Foote again confirmed that the Institute is an independent nonprofit corporation and stated that unauthorized personnel would only be admitted with a valid warrant issued by a court. Ex. D., Declaration of George Foote. [emphasis, line, and links added]

It wasn’t until March 14 that the White House purported to fire all the board members so they could replace Moose.

46. On or about March 14, 2025, Trent Morse of the White House Presidential Personnel Office emailed certain members of the Board, including the Board Member Plaintiffs, claiming to inform them of their termination from the Board by President Trump. Those emails did not state any justification for the purported terminations. See Ex. D, Declaration of George Moose.

47. Shortly thereafter, on March 14, 2025, representatives from DOGE and Defendant Jackson appeared at USIP headquarters building requesting access. Because the Institute has administrative jurisdiction over the parcel of land on which its headquarters sits and the USIP building is owned by the Institute, those representatives were denied entry.

48. Later that same evening, Defendants Altik and Cavanaugh returned to the Institute’s headquarters accompanied by FBI Special Agents and presented Mr. Foote with a “resolution” signed by the three ex officio members of the Board purporting to remove Mr. Moose from his position as President of the Institute. Ex. F, Ex Officio Resolution. [emphasis and link added]

There’s nothing in the four — er, five — EOs that Gleason cites that authorizes DOGE to start shutting down agencies (and to the extent it calls for firing people at agencies, it puts agency heads in charge of that). And there’s nothing in the USIP- specific one that authorizes anyone outside the head of the affected entities — so, Moose, until March 14 if you believe he was lawfully fired — to do anything other than receive a report (as Russ Vought did on March 5) and discuss budgets with the head of the entity.

That means the actions DOGE took before Vought received the letter (marked with a line) — and probably the ones that happened at least until Trump claims to have replaced Moose — were not authorized under the scheme Gleason lays out.

She says that every DOGE team member at an agency reports to the agency head.

Every member of an agency’s DOGE Team is an employee of the agency or a detailee to the agency. The DOGE Team members – whether employees of the agency or detailed to the agency – thus report to the agency heads or their designees, not to me or anyone else at USDS.

So even if DOGE wants to claim that James Burnham and Jacob Altik and Nate Cavanaugh (all named defendants in the complaint) were reporting to a different agency — probably OMB, though ProPublica says they’re all lawyers locataed in the Executive Office of the Presidency — the EO shutting USIP down doesn’t even envision OMB to be involved before receiving that March 5 letter. After that, it only envisions OMB discussing budgets with the entity head. It would seem the things DOGE did before that were definitely unauthorized (and in any case not covered under the DOGE agenda), and most of the rest were too.

Judge Beryl Howell rejected USIP’s request for a Temporary Restraining Order yesterday in part because it has enough trappings of a federal entity to come under the recent DC Circuit Court opinion upholding Hampton Dellinger’s firing, and in part because the harms alleged in the complaint are contingent on the takeover being ruled unlawful. (Howell’s logic is quite similar to Richard Leon’s in the analogous US Africa Development Foundation lawsuit.)

Upon further consideration, the Institute may be deemed to sit outside of the executive branch, or the removal protections may be deemed appropriately enforceable within the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence, but plaintiffs did not demonstrate as much in this expedited posture. See generally, Pls.’ Mot. (not addressing Myers or Humphrey’s Executor).Plaintiffs also did not demonstrate irreparable harm because their alleged harm was dependent on their success on the merits. Plaintiffs cited as their irreparable harm their inability to carry out their statutory functions and the harm to the Institute based on defendants’ intent to reduce it to the “statutory minimums” and defendants’ alleged destruction of the Institute’s property. Compl. 1 ¶¶ 59-65. Those harms, however, are dependent on plaintiffs’ success on the merits. Plaintiffs’ counsel can only represent the Institute–and thus properly assert the harms of the Institute–to the extent that plaintiff Board members and former President of the Institute, George Moose, were wrongfully removed. Plaintiffs likewise only suffer harm in their official capacities–the capacities in which they pled, Compl. ¶¶ 7-11–if they must lawfully remain members of the Board.

This may have been an invitation from Howell for plaintiffs to craft their complaint better.

And I don’t understand why they didn’t include an Appointments Clause in their complaint. Because people who were presenting as DOGE took steps to start dismantling the Institute, in defiance of Congress’ apparent intent, while Moose remained in charge.

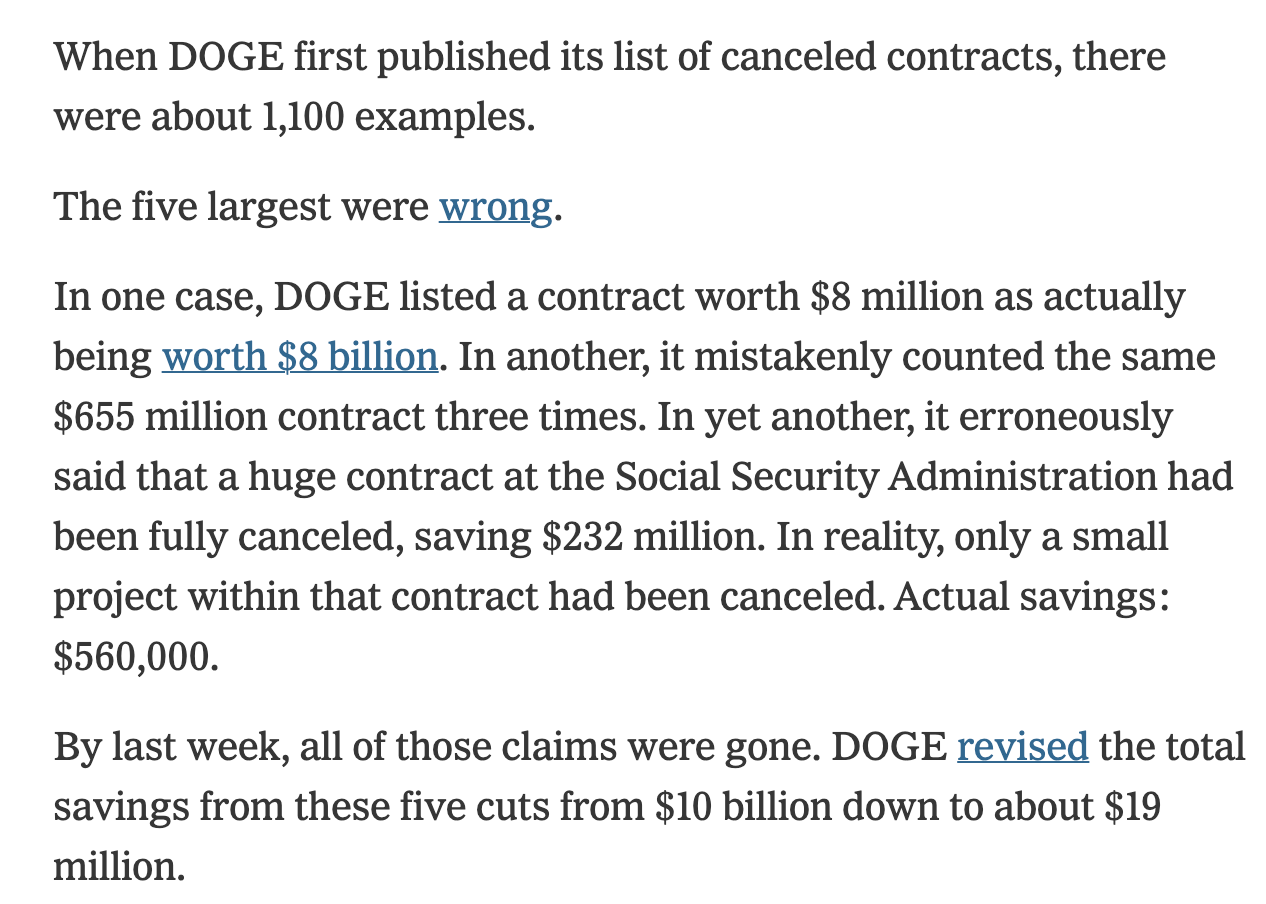

USIP is not the only instance where DOGE took action that appears not to be covered by these four — er, five — EOs. In DOGE’s assault on the US African Development Foundation (which Trump targeted under the same EO), some of the same characters started invading under false pretenses before its head, Ward Brehm, was allegedly replaced on February 24.

4. On February 21, Ethan Shaotran, Jacob Altik, and Nate Cavanaugh arrived at USADF. Shaotran and Cavanaugh introduced themselves as IT personnel from GSA. Altik stated that he was a lawyer from the White House Personnel Office. They explained that we needed to immediately sign a memorandum of understanding for their detail assignment.

5. Once the MOU was signed, Altik explained the true purpose of the meeting, which was to provide USADF leadership with DOGE’s interpretation of the “minimum presence and function” required by USADF’s statute. DOGE read the statute to mean: 1) only the USADF Board and President/CEO are statutorily required, 2) only one or two grants funded by private sector partnerships are required, and 3) all other personnel/employees therefore needed to be eliminated under the Executive Order.

6. Altik stated that his next step was to present a RIF plan (where all USADF staff would be fired) to the board for approval by Monday, February 24. Altik threatened that if the Board didn’t approve the plan, the Board would be dismissed. Both Mathieu Zahui and I tried to explain to Altik that the President’s Executive Order gave the agency 14 days to respond and that we intended to comply with the order.

7. Cavanaugh and Altik then demanded immediate access to USADF systems including financial records and payment and human resources systems, which include staff job descriptions, personnel files, salaries, and organizational structure.

8. Mathieu Zahui outlined the administrative process—which includes security clearances—required to access sensitive data and personally identifiable information from the Agency’s systems. He provided forms for the software engineers to complete to begin background checks.

9. Cavanaugh requested waivers on the clearance process from the USADF board. Altik demanded contact information for all board members and further stated that if the Board was unable to provide immediate clearance to access USADF systems, that he would issue a notice of dismissal to all board members the same day.

[snip]

12. That same day, February 21, after learning that the DOGE team had secured the memorandum of understanding under false pretenses—stating that they would modernize our computer systems but then attempting to shut down USADF— our General Counsel withdrew the MOU.

13. On February 24, Ward Brehm informed USADF that he had received an email from Trent Morse notifying Brehm that he had been dismissed as a board member of USADF. The email was very brief and did not specify any reasons for the dismissal.

There are other instances, though these two are notable because representatives of DOGE started dismantling two entities before they were decapitated, meaning they couldn’t have been reporting to the entities themselves.

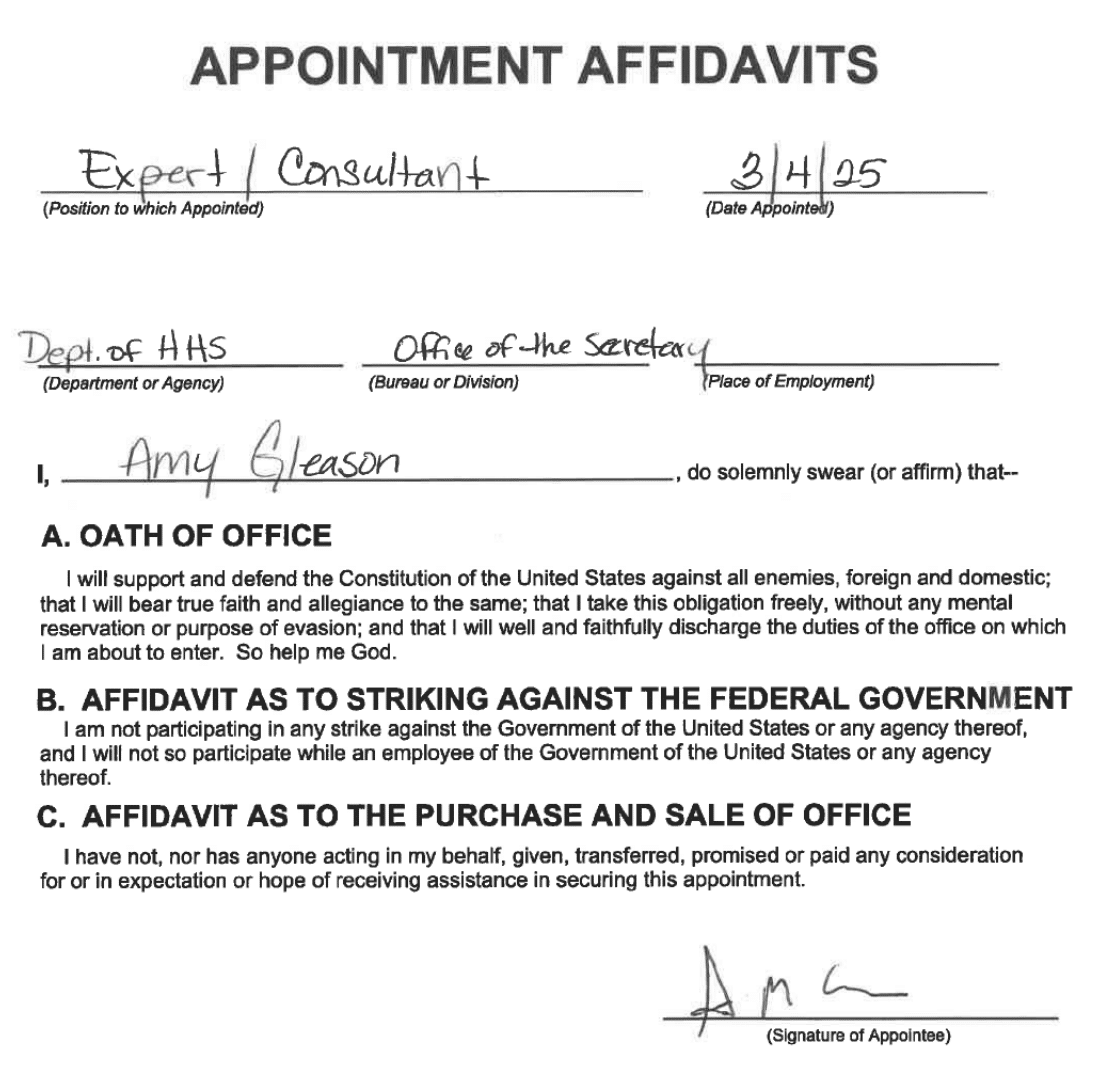

Admittedly, Amy Gleason’s declarations are meant to serve the limited purpose of evading FOIA. As I’ve discussed, her declarations conflict with another document sworn by her claiming to be detailed to HHS. Judges are actively scoffing at these conflicts, so it’s not like we should trust her CREW declarations either.

But until they declare Gleason’s latest to be inoperative, they would seem to lock the government into a statutory arrangement in other cases.