Todd Blanche Kicks Off His Tenure Chasing Leaks Implicating His Own Conduct

Around 8AM on Friday, Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche announced an investigation of a leak to the NYT pertaining to Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua.

The Justice Department is opening a criminal investigation relating to the selective leak of inaccurate, but nevertheless classified, information from the Intelligence Community relating to Tren de Aragua (TDA). We will not tolerate politically motivated efforts by the Deep State to undercut President Trump’s agenda by leaking false information onto the pages of their allies at the New York Times. The Alien Enemies Proclamation is supported by fact, law, and common sense, which we will establish in court and then expel the TDA terrorists from this country.

While DHS and DOJ and FBI have made less formal announcements about leak investigations, most notably an evolving claim that leaks from the FBI or maybe DHS or who knows whether this is all a lazy excuse had tipped off alleged TdA members of imminent immigration operations, this was notable in its formality (which, admittedly, may stem exclusively from the fact that Blanche not a Xitter addict like Kristi Noem, Pam Bondi, and Kash Patel). The announcement was even more notable given Blanche’s claim that the leak was “inaccurate,” which would seem to undercut any claim it was classified.

This was, formally at least, maybe just the third public announcement that Blanche made as DAG (though he has already made a stink defending his client Donald Trump in court cases), with one of the others inviting people to claim they’ve been victims of DEI discrimination.

It appears, though no one has said explicitly, the investigation is into the leak claiming that the Intelligence Community disagrees with Trump about TdA’s ties to the Venezuelan government.

President Trump’s assertion that a gang is committing crimes in the United States at the direction of Venezuela’s government was critical to his invocation of a wartime law last week to summarily deport people whom officials suspected of belonging to that group.

But American intelligence agencies circulated findings last month that stand starkly at odds with Mr. Trump’s claims, according to officials familiar with the matter. The document, dated Feb. 26, summarized the shared judgment of the nation’s spy agencies that the gang was not controlled by the Venezuelan government.

The disclosure calls into question the credibility of Mr. Trump’s basis for invoking a rarely used wartime law, the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, to transfer a group of Venezuelans to a high-security prison in El Salvador last weekend, with no due process.

The intelligence community assessment concluded that the gang, Tren de Aragua, was not directed by Venezuela’s government or committing crimes in the United States on its orders, according to the officials, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal deliberations.

Analysts put that conclusion at a “moderate” confidence level, the officials said, because of a limited volume of available reporting about the gang. Most of the intelligence community, including the C.I.A. and the National Security Agency, agreed with that assessment.

Only one agency, the F.B.I., partly dissented. It maintained the gang has a connection to the administration of Venezuela’s authoritarian president, Nicolás Maduro, based on information the other agencies did not find credible.

The story was published on March 20, before the investigation announcement, but only published in the dead tree NYT after it.

If that’s correct, the investigation that Blanche rushed to formally announce implicates his own behavior.

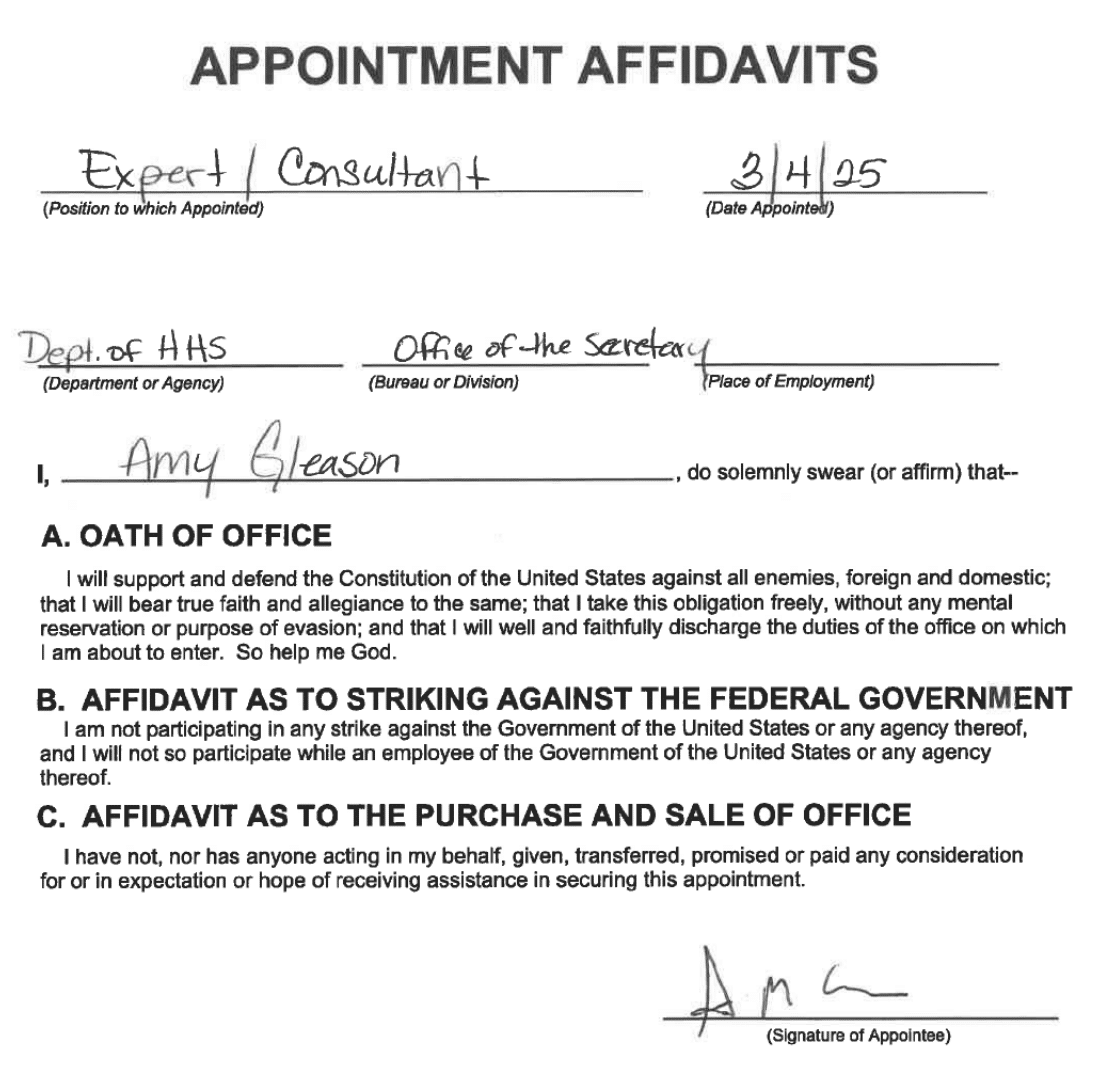

Blanche’s announcement came the same day that he filed an insolent declaration before Judge James Boasberg, adopting the claim made by a regional ICE official in a declaration submitted one day earlier: The government is considering invoking State Secrets to withhold from Boasberg even the most basic details of deportation flights that brought Venezuelans to El Salvador after he ordered them to turn.

2. On March 20, 2025, the Government submitted a declaration from Robert L. Cerna II, which stated: “I understand that Cabinet Secretaries are currently actively considering whether to invoke the state secrets privilege over the other facts requested by the Court’s order. Doing so is a serious matter that requires careful consideration of national security and foreign relations, and it cannot properly be undertaken in just 24 hours.”

3. I attest to the accuracy of those statements based on personal knowledge of the events described by Mr. Cerna, including my direct involvement in ongoing Cabinet-level discussions regarding invocation of the state-secrets privilege.

DOJ wants to withhold those details even though some details of which were leaked to Fox News Deportation Propagandist Bill Melugin right away, other details of which are readily available on flight tracker websites.

Judge Boasberg’s order demanding such a cabinet-level declaration came before Blanche’s leak investigation announcement.

Which is to say NYT was working on this intelligence assessment story even as DOJ was stonewalling Boasberg about why it deported two or three planeloads of Venezuelans after he ordered DOJ not to.

Whether or not Trump’s DOJ invokes State Secrets Tuesday, there’s plenty of information in the public record — including the NYT story — that would undercut, but also explain, such an invocation.

CBS published a list of the Venezuelans who were deported — the kind of leak that elicited heavy pushback when they involved Gitmo under George Bush, and almost certainly had to come from some kind of internal documentation but was not obviously implicated in Blanche’s investigation announcement.

The plaintiffs filed declarations debunking the government’s claims that the men deported or targeted to be were criminals, much less members of TdA. There was plenty of other reporting on missing family members who seem to have been deported based on soccer tattoos.

NYT and WaPo both have stories suggesting the underlying reason this trade happened: Because El Salvador’s authoritarian President Nayib Bukele is anxious to get MS-13 members who could implicate him in terrorism out of US custody. Here’s WaPo’s (later) story:

Some say Bukele is trying to hide his government’s own involvement with the gangs.

More than two dozen high-ranking Salvadoran gang leaders have been charged with terrorism and other crimes in a Justice Department investigation that has lasted years. Several of them are jailed in the United States. One of the indictments details how senior members of Bukele’s government held secret negotiations with gang leaders after his 2019 election. The gang members wanted financial benefits, control of territory and better jail conditions, the court documents say. In exchange, they agreed to tamp down homicides in public areas and to pressure neighborhoods under their control to support Bukele’s party in midterm elections, according to the 2022 indictment.

Bukele’s government went so far as to free a top MS-13 leader, Elmer Canales Rivera, or “Crook,” from a Salvadoran prison, according to the documents — even though the U.S. government had asked for his extradition. (He was later captured in Mexico and sent to the U.S.)

Last weekend, the Trump administration sent back one of the MS-13 leaders named in the indictments, César Humberto López Larios, alias “Greñas,” along with the 238 Venezuelans and nearly two dozen other Salvadorans allegedly tied to gangs.

Some Salvadoran analysts believe Bukele wants the gang leaders back so they won’t testify about his government’s involvement with them — and potentially put him in legal trouble.

“If these returns [of Salvadoran gang members] continue, it takes away the possibility that the U.S. judicial system will open a case against Bukele for negotiations and agreements with terrorist groups,” said Juan Martínez d’Aubuisson, an anthropologist who has studied the gangs.

The possibility that this effort to outsource detention and torture to Bukele is part of a quid pro quo helping a fellow authoritarian to cover up his own criminal ties is not dissimilar from details about Saudi complicity in 9/11 that the Bush Administration spent years invoking State Secrets to cover up.

And then finally, in plain sight, on Friday Trump disclaimed that he personally had signed the Alien Enemies Act declaration, that someone used an autopen for his signature. If true (I certainly don’t rule out Stephen Miller autosigning half the stuff that comes out under Trump’s name), that would undermine the Article II claims the government is making.

In other words, even as the government claims to be contemplating invoking State Secrets (which would require declarations to Boasberg I’m not sure they’re willing to provide), the following details have come out:

- Names and details of the detainees, debunking the claims of TdA affiliation on which Trump based their deportation, making it clear that Trump rushed these deportations to avoid disclosing that TdA isn’t what he says it is

- Good reason to question the underlying quid pro quo with Bukele

- Trump’s claim that the AEA order was not backed by the Article II authority DOJ has spent a week claiming it is.

- The likely subject of the leak investigation: Claims from spooks that any intelligence to support this AEA effort is based on flimsy intelligence

This is the kind of fact set that has the potential to snowball.

Meanwhile, just two months into this Administration, it’s already investigating leaks about purportedly internal spats. Unrelated to Venezuela, there was the NYT leak disclosing Pete Hegseth was about to brief Elon Musk about DOD’s plans for war with China, in response to which Elon called for leak prosecutions.

The chief Pentagon spokesman, Sean Parnell, initially did not respond to a similar email seeking comment about why Mr. Musk was to receive a briefing on the China war plan. Soon after The Times published this article on Thursday evening, Mr. Parnell gave a short statement: “The Defense Department is excited to welcome Elon Musk to the Pentagon on Friday. He was invited by Secretary Hegseth and is just visiting.”

About an hour later, Mr. Parnell posted a message on his X account: “This is 100% Fake News. Just brazenly & maliciously wrong. Elon Musk is a patriot. We are proud to have him at the Pentagon.”

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth also commented on X late on Thursday, saying: “This is NOT a meeting about ‘top secret China war plans.’ It’s an informal meeting about innovation, efficiencies & smarter production. Gonna be great!”

Roughly 30 minutes after that social media post, The Wall Street Journal confirmed that Mr. Musk had been scheduled to be briefed on the war planning for China.

In his own post on social media early Friday, Mr. Musk said he looked forward to “the prosecutions of those at the Pentagon who are leaking maliciously false information to NYT.”

The leak served a very important (and presumably, its intended) purpose: NYT subsequently reported that Trump had not known about the briefing.

Mr. Trump made clear he had been caught by surprise by The Times’s report, saying he called his White House chief of staff and Mr. Hegseth to ask about it; he said they said it was “ridiculous.” But he also said that Mr. Musk — who has extensive business in China — should not be made aware of such sensitive information. It was one of the first specific statements from the president about what he would consider a bridge too far for Mr. Musk, who has expansive potential conflicts of interest created by a portfolio as a part-time government staff member and adviser.

Yet CNN reported that DOD would conduct an investigation, using polygraphs, which the article explicitly suggests is a reference to this leak.

We’re used to these people doing suspect things to cover up Trump’s alleged crimes. But it took just days for Todd Blanche to involve himself personally in all this, even while siccing investigators on those who might debunk the legal claims he’s making in court. And the DOD leak suggests these are not just — as Blanche claimed in his investigation announcement — the Deep State undermining Trump.

These are, in part, people trying to prevent Trump from making bigger fuck-ups than he’s already making.

Update: Corrected date State Secrets declaration is due.

Update: I said the Todd Blanche announcement was 8AM, based off the time listed on the press release. But it was not sent out until hours later, after the status hearing.

Timeline

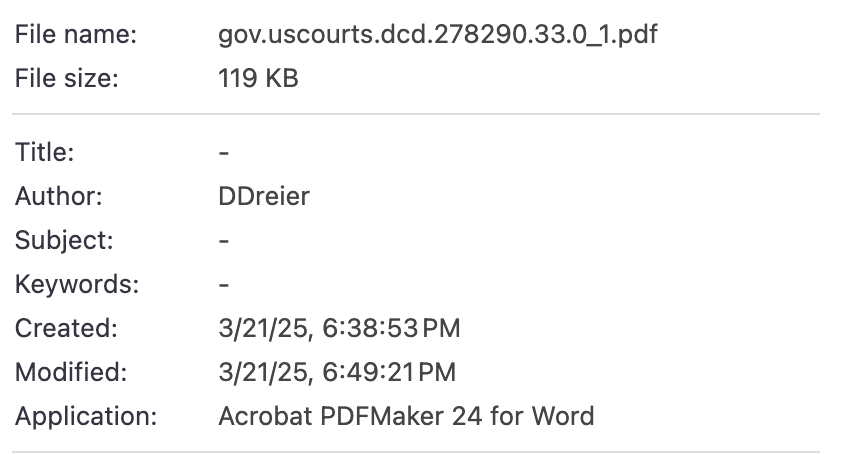

[docket]

March 14: Trump issues but does not publish AEA proclamation

March 15: Proclamation posted

March 15: Boasberg certifies class, issues TRO

March 15: Emergency hearing

March 15, 7:25: Boasberg order

March 17: NYT Bukele story

March 17: Boasberg orders briefing on post-order deportations by March 18 at noon

March 17, 5PM: Boasberg hearing

March 18: First Cerna declaration

March 18: Boasberg orders March 19 declarations on details of deportation

March 19: Boasberg partially grants request for extension

March 20, 12:11PM: Second Cerna declaration

March 20, 3:49PM: Boasberg orders a cabinet level declaration

March 20: WaPo Bukele story

March 20 (around 6PM?): NYT publishes intelligence assessment story

March 20, 8:18 PM: CBS publishes list of deported Venezuelans

March 21, AM, 8AM: Blanche announces the investigation

March 21, 12:18: Blanche submits a declaration

March 21, 2:30PM: Motion hearing

March 21: Trump disclaims signing AEA declaration