Une FAQ Utile

(My friend Meor and @rafi0t have traslated my Covid-19 FAQ into French for the francophones out there- QN; Ed: for those who missed the English version the first time, it is here.)

1. Vais-je mourir?

Oui, malheureusement, tout le monde meurt.

2. Non, je veux dire est ce que je vais mourir du Covid 19?

Ah, ça! Probablement pas. La plupart des personnes touchées et malades présentent des symptômes assez mineurs. Par mineur, comprends que ta vie ne sera pas en danger direct, mais ça ne sera pas non plus une expérience très agréable. Selon les estimations actuelles, 80% des cas sont mineurs, 20% nécessitent une intervention médicale et quelque part entre 0,7% et 5% peuvent causer le décès ou s’en rapprocher suffisamment pour avoir une lumière brillante pointée dans leur direction.

3. Tu parles d’une expérience de mort imminente pour 5% des gens?

Non, je parle de l’éclairage d’hôpital, il est tellement lumineux et désagréable! Ça me donne mal à la tête à chaque fois. Ne peuvent-ils pas utiliser des ampoules aux teintes plus chaudes?

4. Je pose les questions ici.

Soit. Désolée, continue.

5. Est ce que beaucoup de personnes devront être hospitalisées?

Il semblerait. La plupart des personnes de plus de 70 ans et des personnes souffrant de problèmes de santé auront besoin de ce qu’on appelle des «soins de soutien». Ils sont dits “de soutien” car nous n’avons pas de remède ou de traitement direct contre ce virus. Ce que nous pouvons faire c’est maintenir la personne en vie pendant qu’elle se bat pour créer suffisamment d’anticorps, tuant ainsi les virus en balade en son intérieur. Concrètement, cela peut signifier un supplément d’oxygène, une surveillance par le personnel de santé, voire carrément un respirateur pour le patient.

6. Que faisons-nous à propos du trop grand nombre de personnes devant se rendre à l’hôpital en même temps?

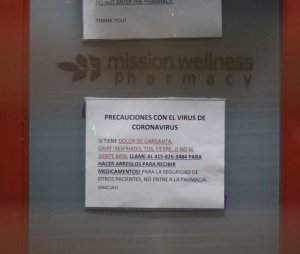

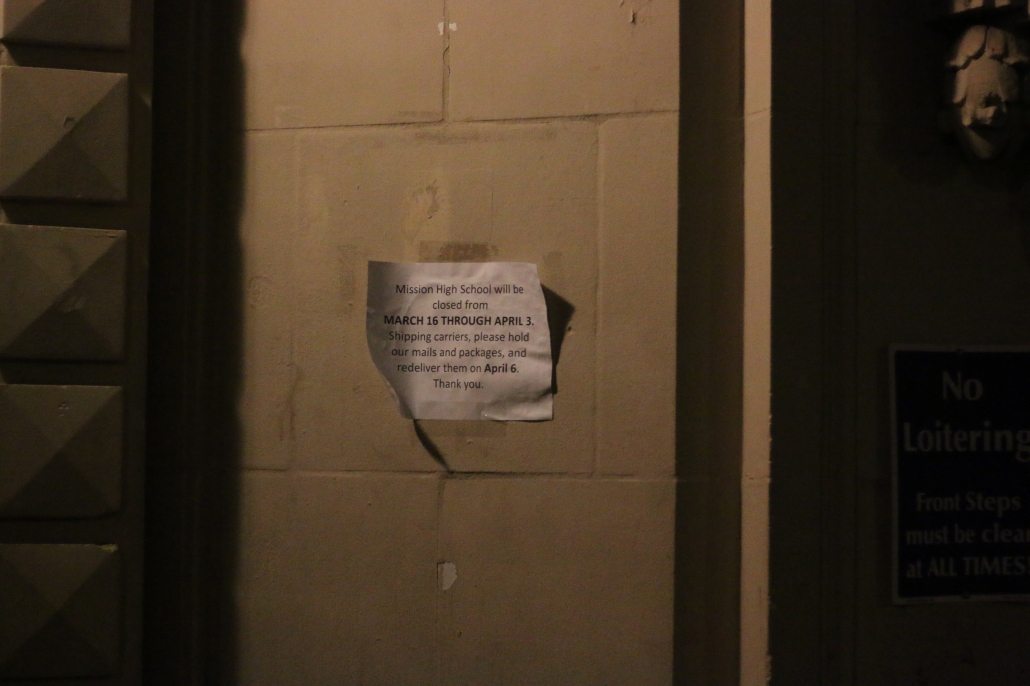

C’est précisément le scénario cauchemardesque que nous essayons d’éviter, en mettant en oeuvre ce que les épidémiologistes appellent le ralentissement, pour réduire le taux de personnes qui se rendent à l’hôpital. Pour ralentir la propagation du virus, tu peux te laver les mains, nettoyer les surfaces autour de toi (plus de détails bientôt) et éviter de te rapprocher des autres personnes à l’extérieur. Mais les maires, les députés, les administrations scolaires et les autres autorités en charge de ces espaces où de nombreux gens sont proches peuvent faire beaucoup plus : en annulant les événements, en encourageant le travail à domicile, en fermant les écoles et les universités et en limitant le nombre de personnes autorisées à se rassembler ainsi que leur proximité.

Chaque endroit où le public se réunit devient un lieu où le virus passe d’une personne à l’autre. C’est essentiel car, si nous pouvons ralentir la propagation, la file d’attente pour les si confortables lits des soins intensifs sera équilibrée dans le temps et tout le monde ne se précipitera pas sur des respirateurs comme c’était Black Friday version santé.

Voici un excellent graphique expliquant ce que nous essayons de faire avec toutes ces distanciations sociales et le lavage des mains, en particulier le lavage des mains. Ai-je mentionné l’importance de se laver les mains?

The pokey curve is uncontrolled infections, the smooth, slower curve we want is what we want by delaying the spread.

La courbe en pointe correspond à des infections sans aucun contrôle, la courbe lisse et plus lente est ce que nous essayons d’accomplir en retardant la propagation.

7. Pourquoi n’avons-nous pas de remède? Je dois souffler dans les bronches de qui à ce propos?

Écoute, nous vivons dans une telle époque des merveilles, de duplicité politique et d’inepties qu’on pourrait se dire, dès que’un mauvais événement arrive, “Il ne peut que s’agir de négligence ou de malveillance”. Le fait est que la nature peut toujours nous botter le cul à tout moment. Ce n’est la faute de personne, c’est le genre de chose à laquelle les êtres humains ont dû faire face bien avant que nous soyons… humains.

8. Il doit bien y avoir quelqu’un sur qui crier quoi quelque chose?

Ne t’inquiète pas : Il y en a! Les autorités comme les personnes les plus banales peuvent faire beaucoup pour ralentir la propagation de cette maladie et rendre le traitement plus efficace.

Sur le plan personnel, tu peux crier après tes enfants / colocataires / parents / etc. de se laver les mains pendant 20-30 secondes plusieurs fois par jour, avant et après être sorti, avant de préparer la nourriture, d’utiliser les toilettes, de toucher de la nourriture, de se toucher le visage, d’éternuer, de tousser, de cracher ou de jurer…

9. Attends, jurer?

Oh, ça ne peut pas faire de mal.

10. Ah. ok. Continue.

Tu peux aussi nettoyer régulièrement les surfaces touchées fréquemment – pense poignées de porte, de tiroirs, comptoirs, interrupteurs, claviers, boutons, robinets … la boite de pétri ambulante qu’est ton téléphone portable, regarde simplement les espaces qui t’inquiètent, publics ou privés et pense aux endroits que les gens touchent, où ils toussent, éternuent ou qu’ils lèchent.

11. LÈCHENT? Tu sais quoi, je ne veux pas savoir. Avec quoi dois-je tout nettoyer? Alcool, eau de javel, feu?

Toutes ces choses fonctionneront, mais honnêtement, le savon ou les nettoyants de surface de base sont très bien. Les lingettes désinfectantes sont idéales pour un nettoyage rapide et pour les téléphones portables, mais tu peux aussi utiliser un nettoyant ménager habituel, vaporisé en bonne quantité puis bien essuyé avec de l’essuie tout, y compris ton téléphone portable dégoûtant. Le savon (détergent) est nickel aussi. En fait, c’est souvent mieux que l’alcool ou le peroxyde d’hydrogène. Il faut se souvenir d’une chose, ce coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, a un seul brin d’ARN et quatre protéines spécialisées toutes soutenues par une bi-couche lipidique qui maintient le paquet ensemble. Le fait d’avoir une enveloppe virale lipidique le rend sensible aux détergents…

12. Tu peux arrêter de nerder?

Pardon. Si tu mets du savon sur le virus et que tu frottes un peu, il éclate, puis il disparaît.

13. Wow!

N’est-ce pas? Tu peux bien sûr y mettre le feu, y verser de l’alcool ou autre produit de ton choix, mais il suffit de quelque chose qui dissout la graisse et de quelques petits va-et-vient. Et là, tu peux imaginer ces minuscules petites boules hérissées éclater et déverser leurs minuscules petites tripes partout. C’est une chouette image. Ça donne envie de tout frotter.

Le gel hydroalcoolique fonctionne de la même façon, bien qu’il soit moins efficace que du savon ordinaire. Il y a toutes sortes de produits de nettoyage, mais ce bon vieux savon fait parfaitement l’affaire. Tu ne veux pas non plus utiliser des produits qui dessèchent et provoquent des gerçures dans la peau – toute tâche sanguinolente est un point d’entrée. Cela pourrait également signifier que tu devrais te procurer de quoi garder tes mains douces, souples et exemptes de trous superflus.

En bref, et très sérieusement, lave-toi les mains avec du savon et de l’eau et ne te touche pas le visage. C’est à peu près la meilleure chose que chacun puisse faire!

Voici une vidéo de Baby Shark avec des danseurs montrant la bonne technique de lavage des mains, et en voici une autre. Internet regorge de ce type de choses…

14. D’accord, mais revenons à la partie où je vais crier sur des gens à ce sujet.

Bien sûr. Le virus se transmet d’une personne à l’autre par les microgouttelettes que nous toussons, éternuons ou même expirons. Cela inclut potentiellement nos larmes, nos crachats, notre sang et nos affaires dans la salle de bain. Ça fait beaucoup de moyens de transmission interpersonnels, et cela signifie que nous devons nous tenir éloignés les uns des autres pour ralentir la propagation de ce virus.

Tu peux alpaguer les responsables locaux et autres organisateurs d’événements pour faire annuler ou reporter les rassemblements impliquant des contacts assez étroits entre personnes, y compris ceux qui concernent des enfants. Les écoles, les conférences, les services religieux et d’autres annulations d’événements publics sont déjà en cours et elles devraient se multiplier. Tu peux alerter avec véhémence les autorités locales à ce sujet!

15. Qu’en est-il des tests?

Oh, tu peux crier à plein poumons à ce sujet!

Les tests, en particulier aux États Unis, ont été ridicules. Le dépistage généralisé est l’un des meilleurs moyens de cartographier et donc de contenir toute épidémie, notamment lorsque de nombreuses personnes (en particulier les enfants) semblent présenter des symptômes bénins, il est encore plus important d’avoir des tests largement disponibles.

Idéalement, les tests devraient être accessibles à tous au sein d’une zone infectée. La Corée du Sud a effectué des tests, la Chine a rendu une grande partie de ses tests obligatoires.

Dans la plupart des cas, si tu as le virus, il te suffit de le savoir pour que tu sois confiné chez toi jusqu’à ce qu’il passe. Mais si tu ignore être porteur du virus, tu peux le répandre, ce qui est exactement ce que font de nombreuses personnes qui se sont vues refuser le test aux États-Unis, en Australie, au Japon et bien d’autres pays. Tester uniquement les personnes les plus malades confirme leur propre situation, mais ne renseigne pas sur la façon dont le virus pourrait se propager en ce moment. Les personnes très malades ne se promènent plus vraiment en toussant. À certains égards, il est moins important de savoir si les très malades ont le virus que de connaître les malades qui marchent encore, peuvent en être atteints… et le transmettre!

Quelle que soit la cause du retard des tests aux États-Unis, l’excuse n’est pas assez bonne.

16. Covid 19 est-il la faute de Trump / Mitch McConnell / Nancy Pelosi / Jay Inslee / Gavin Newsom / Rush Limbaugh / Etc.?

Honnêtement, au moment où nous sommes, peu importe le ou les fautifs. “La maison est en feu et nous devons l’éteindre.” comme dit l’adage. Nous pourrons découvrir qui blâmer quand ce sera réglé. L’urgence est de commencer à tester le plus largement et le plus rapidement possible et de transmettre ces informations aux différentes communautés pour les aider à prendre des décisions basées sur de bonnes données, et de façon compréhensibles.

De plus, pour être prudent, ne lèche pas les pangolins que tu rencontres.

17. Comment puis-je faire en sorte que mon oncle / ma mère / mon enfant / moi-même arrête de FLIPPER COMPLÈTEMENT à ce sujet?

Si tu lis ceci, tu n’es probablement pas un professionnel de la santé travaillant en première ligne de la réponse ou un administrateur qui planifie la logistique dans ta région. Tu n’as donc tout bonnement pas besoin de connaître les dernières nouvelles et spéculations sur Covid 19. Ce qui vaut vraisemblablement pour ton enfant, ton conjoint, ton cousin ou ton chat. Informé c’est bien, mais noyé dans l’information et paralysé émotionnellement c’est mal.

Choisis un moment de la journée pour recevoir tes nouvelles sur Covid 19, puis … arrête.

Si c’est vraiment nécessaire pour toi, vas-y et vérifie deux fois par jour.

Si des gens en parlent autour de toi, parle de la bonne procédure pour se laver les mains et du nettoyage des surfaces jusqu’à ce qu’ils n’en puissent plus. Personne ne veut parler autant de nettoyage des mains comme des surfaces, sauf moi, peut-être.

Si tu as affaire à un être cher qui pique une crise, mets en place une activité : un jeu de société, un film, quelque chose qui procure une pause. Débranche accidentellement ton accès Internet pendant un certain temps. Si tu as le sentiment que tu dois faire quelque chose, nettoie la maison, cela ne peut pas faire de mal. Imprime des affiches sur le lavage des mains et place-les dans les salles de bain que tu visites. Varie tes activités et surtout parle d’autres sujets. Le monde tourne toujours, il y a des livres à lire et des films à regarder et des choses à faire : avoir peur de Covid 19 n’est pas ton travail à plein temps.

18. Est-ce l’Apocalypse Zombie?

Non, ce n’est qu’un énième virus chiant qui cause une mauvaise infection pulmonaire. Il y en a beaucoup, mais parce que celui-ci est nouveau, pour nos organismes comme nos chercheurs, nous n’avons aucune immunité. Ça va être difficile et triste pendant un moment.

19. Tu vois ce que je veux dire. Ce virus… Est-ce l’état profond ou une arme biologique échappée d’un laboratoire maléfique du gouvernement? Est-ce que le virus SARS-CoV-2 sera joué par Dwayne «The Rock» Johnson un jour, quand la vérité sera révélée?

Oh Seigneur, OK, tu gardais cette question pour la fin. Permets-moi de te dire à quel point ce genre de chose est aussi ennuyeux qu’inévitable.

Ce nouveau virus appartient à une famille de virus appelés coronavirus. Ils ont été découverts dans les années 1960. La plupart d’entre eux provoquent des symptômes du rhume courants. Ce sont des virus à ARN génétiquement similaires, mais tu peux presque les considérer comme de simples machines pour injecter de l’ARN dans certaines cellules qui en font ensuite involontairement des copies. Mais rien de tout cela n’est très précis, et les erreurs pénètrent constamment dans la prochaine génération de virus à ARN, c’est ainsi que nous nous retrouvons avec de nouveaux virus. C’est à peu près aussi malveillant que des Roombas qui se reproduisent: un peu malveillant certes, mais aussi un peu stupide. Les nouveaux virus émergents provoquant des épidémies sont inévitables, ils se produisent non seulement depuis plus longtemps que l’humanité, mais avant même que nous soyons des animaux.

Et non seulement la création d’une arme biologique virale qui tue principalement les personnes âgées et les personnes immunodéprimées est impossible avec la technologie actuelle, elle n’est pas non plus particulièrement utile.

Ce n’est pas le seul nouvel agent infectieux que nous verrons, ce n’est même pas le seul que nous ayons vu ces dernières années – SRAS, MERS, SIDA, H1N1, Ebola, SARM, ce sont tous de nouveaux (plus ou moins) agents infectieux contre lesquels nous nous battons. Alors que nous perturbons les habitats et envahissons les grottes des chauves-souris, les virus et les bactéries qui ne sont pas déjà allés dans notre corps finiront par tenter le coup. La plupart d’entre eux échoueront et nous ne saurons jamais rien de leurs tentatives, dans notre corps, à la recherche de quelque chose sur quoi s’accrocher. Mais de temps en temps, l’un de ces minuscules salauds cochera les bons numéros du Loto. C’est la raison même de l’existence des domaines scientifiques et cliniques de l’épidémiologie. Nous avons tendance à l’oublier, en pleine époque de techno-merveilles, mais la nature est toujours le boss de fin.

20. C’est déprimant et un peu décevant.

Je sais. Peut-être pouvons-nous demander à Dwayne Johnson de jouer le Dr Tedros Adhanom, chef de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS) qui démonterait les gens refusant de se soumettre à des tests et exigeant que le public soit autorisé à rentrer chez lui et à pratiquer la distanciation sociale.

21. Okay, c’est une idée terrible pour un film. Et soit, ce n’est pas un complot secret du gouvernement. Si je ne suis même pas un zombie, comment savoir si j’ai Covid 19?

Les symptômes à surveiller sont la fièvre, l’essoufflement (difficulté à respirer) et la toux.

22a. Whoa attends exactement ce que je-slash-la personne qui lit ceci à côté de moi a! QU’EST-CE QUE JE FAIS MAINTENANT?!

Tout d’abord, calme toi. Ceux-ci peuvent être des symptômes courants de la grippe, et heureusement, la grippe (avec son taux de mortalité beaucoup plus faible) est encore plus courante. Mais si tu te trouves dans une zone de transmission ou si tu as récemment voyagé dans une zone où une épidémie s’est déclarée, cela vaut la peine de se faire dépister si des tests sont disponibles. Si tu es malade, ne vas pas à l’hôpital ni chez le médecin, tu mettrais d’autres personnes en danger. Appelle ton médecin ou la ligne d’urgence dédiée et dis-leur pourquoi tu penses que tu pourrais avoir Covid 19.

Si tu es très malade et que tu devras te rendre à l’hôpital, appelle une ambulance et préviens les que tu soupçonnes une infection par le Covid 19. Ainsi, ils pourront se présenter avec le bon équipement pour assurer ta sécurité et celle des autres.

22b. J’ai un nez qui coule et un mal de gorge et je me sens généralement un peu merdique.

On se calme. J’ai ça aussi, c’est un rhume. C’est pourquoi cette FAQ est si tardive.

23. Est-ce que tout cela disparaîtra quand il fera plus chaud?

Eh bien… c’est difficile à dire. Version courte, la réponse est non, mais c’est peut-être possible? Cela dépend en grande partie de la façon dont le virus du SRAS-CoV-2 survit sur les surfaces, et il ne survit pas aussi longtemps sur des surfaces chaudes, ou n’aime pas être frappé par les rayons UV du soleil. Cela pourrait, en théorie, réduire l’infectiosité globale de la maladie, mais nous n’en savons rien pour l’instant.

24. J’ai une très bonne assurance maladie, ça veut dire que je suis cool, non?

Oh, désolé, mais pas cette fois. Le principal problème est de savoir si nous pouvons ralentir le virus suffisamment pour nous assurer que les lits d’hôpitaux et les services qui y travaillent ne sont pas pleins et débordés lorsque tu en auras besoin.

Quelle que soit la qualité de ton assurance maladie, si les hôpitaux n’arrivent pas à traiter suffisamment rapidement les personnes malades et que l’épidémie est en expansion, tu vas devoir attendre… et les conséquences peuvent être douloureuses. Ai-je trop parlé de se laver les mains?

25. Pourquoi les enfants sont-ils immunisés? Pourquoi ne souffrent-ils pas comme nous tous?

Compliqué, mais allons-y. Les enfants ne sont pas immunisés : ils attrapent le virus dans le même délai et l’ont probablement aussi longtemps que nous les adultes. Ils ne semblent tout simplement pas avoir beaucoup de symptômes. Si tu mets un coton-tige dans leur nez, tu pourras détecter le virus, mais ils ne présentent pas de signe de maladie. Quant à savoir pourquoi… Ils pourraient avoir très peu d’activité virale et ainsi répandre le virus comme de minuscules et adorables Mary Typhoïde partout sur leurs grands-parents. Il y a beaucoup de choses que nous ignorons encore totalement sur ce virus ou ce qu’il fait dans le monde. C’est nouveau, c’est difficile à gérer. De nombreux articles sortent, de nombreux scientifiques se ruent sur toutes les données dont nous disposons. La recherche sur Covid 19 est peut-être l’une des seules choses à voyager plus vite que le virus en question, mais il reste encore beaucoup à comprendre.

26. Quelle distance sociale dois-je pratiquer?

Cela dépend en partie de toi. Si tu es plus âgé, immunodéprimé ou à risque élevé, tu devrais probablement te préparer à rester à la maison pendant quelques semaines si le virus arrive en ville.

S’il est déjà en ville, évite les foules et les transports en commun bondés. Travaille à domicile si c’est possible et prépare toi à la fermeture des écoles.

Si tu es malade d’une autre maladie et que tu dois sortir, c’est le moment de porter un masque, un masque chirurgical est très bien.

Lave-toi les mains et ne te touche pas le visage.

Si tu es touché par le Covid 19, vraiment, ne sors pas. Essaye de te faire livrer tout ce dont tu as besoin jusqu’à ce que tu te rétablisses.

27. Une fois que j’irai mieux et que j’aurai vaincu le virus, je serai un super-héros invulnérable au coronavirus, non?

Eh bien, euh, il y a plus d’une souche du virus, et nous ne savons pas si avoir survécu à l’un d’eux confère une immunité générale. Jusqu’à ce que nous le sachions, tu devrais faire encore attention.

28. SÉRIEUSEMENT?!

Oui, nous en saurons probablement plus bientôt, mais comme je le répèté, c’est nouveau, nous sommes tous en processus de compréhension.

Pardon.

29. Il semblerait que je vive avec quelqu’un qui a le virus et que je doive m’en occuper, ou cette personne est dans une catégorie à risque et je m’inquiète de le leur transmettre.

Cela dépasse le cadre d’une FAQ sarcastique, mais je vais essayer.

Si tu vis avec une personne vulnérable, tu dois t’astreindre immédiatement à l’éloignement social, l’auto-isolement et suivre les mesures de sécurité.

Si tu prends soin de quelqu’un, c’est exactement la situation dans laquelle tu as besoin d’équipement de protection individuelle comme des masques N95, des gants, etc. Attention : tu dois ajuster les masques correctement. Les tutoriels Youtube sont tes amis.

30. Dois-je aller à l’école? Travailler? Puis-je quand même sortir manger? Ou obtenir la livraison? Je ne sais pas comment faire bouillir de l’eau…

Cela dépend en grande partie de ce qui se passe et de là où tu te trouves. Il devrait y avoir des annonces locales sur les écoles, le travail et les rassemblements qui aident à guider tes décisions, mais tu devras peut-être être plus prudent en fonction de ta propre situation de santé.

En ce qui concerne la préparation de plats, un repas cuisiné va tuer le virus, mais il serait bien que les personnes travaillant dans les cuisines commerciales portent des masques et se lavent beaucoup les mains. Si tu sors, ne vas pas pas dans un endroit bondé. Tu veux entre 1.5m et 2m entre chaque personnes, avec une bonne ventilation. Si tu reçois te fais livrer, assure toi que tes aliments sont chauds et traite les sacs et contenants comme s’ils étaient contaminés – lave-toi les mains, jette l’emballage, lave toi les mains à nouveau.

31. Que fais tu à ce sujet, toi, hein, Quinn?

(Version originale: Oh, mets mon argent là où est ma bouche, hein? (C’est une idée terrible, l’argent est presque toujours contaminé, alors j’utilise autant que possible ma carte de crédit)

—

Oh, faites ce que je dis pas ce que je fais? Mais je parle beaucoup, tu as vu…” Alors, je suis actuellement à San Francisco, où il n’y a pas (encore) de crise médicale mais nous avons une transmission communautaire. L’école de ma fille est toujours ouverte, ce qui me déplaît, mais pour l’instant elle s’y rend. Quand j’avais des symptômes de rhume, je portais un masque. Je vérifie régulièrement ma température, tout comme mes colocataires. Je me lave beaucoup les mains. J’essuie les surfaces très sensibles avec du détergent plusieurs fois par jour.

Ma fille et moi prenons des multi-vitamines. Certaines personnes pensent que le zinc peut aider, ou la vitamine D, ou C, ou quoi que ce soit, et honnêtement, personne ne le sait – c’est un nouveau virus! Ce dont je suis sûr, c’est que les carences aggravent la maladie et qu’un apport en multi-vitamine ne peut pas faire de mal. (Sauf que les hommes biologiques ne devraient pas prendre de vitamines pour femmes en raison du fer qu’ils contiennent.) Je sors encore et je fais quelques activités, mais je ne fais pas la queue ni ne m’approche des gens. Je suis allé à Safeway, j’ai vu des lignes et je suis sortie aussi sec. Je marche généralement pour me déplacer, mais je prendrais plutôt un tram presque vide. Je fais toujours des courses et je vois des gens promener des chiens. C’est bon, tant que nous restons bien éloignés les uns des autres. Quand je reviens… devine : je me lave les mains.

32. Où puis-je trouver des informations fiables et moins sarcastiques que cette FAQ?

L’Organisation mondiale de la santé dispose d’un site d’information sur ce nouveau coronavirus

L’Université Johns Hopkins gère également un excellent site informatif

… Ainsi qu’un tableau de bord indispensable pour suivre la progression du virus.

Worldometer (Worldometer appartient à une société appelée Dadax) est un très bon agrégateur avec une belle section sur les coronavirus.

En francais, Le gouvernement a une très bonne FAQ (moins marrante, mais plus complète.

Et le site de la santé publique a aussi beaucoup d’informations.

Recherche également des informations locales du lieu où tu te trouves. En espérant que les dirigeants des administrations locales sont ceux qui les connaissent le mieux.

Ai-je mentionné que tu devrais te laver les mains?