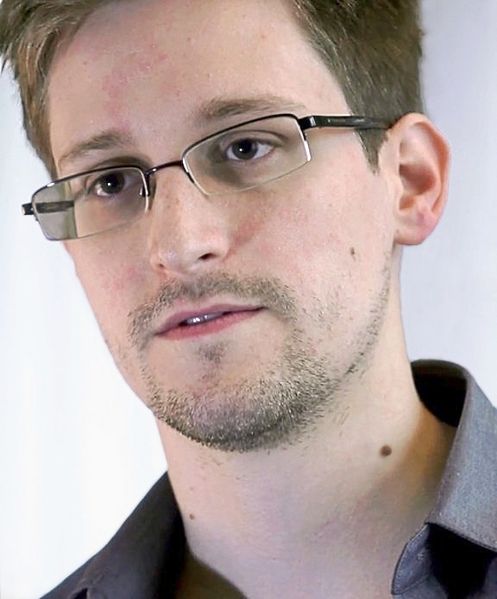

The Government Argues that Edward Snowden Is a Recruiting Tool

As I noted in my post on the superseding indictment against Julian Assange, the government stretched the timeline of the Conspiracy to Hack count to 2015 by describing how WikiLeaks helped Edward Snowden flee to Russia. DOJ seems to be conceiving of WikiLeaks’ role in helping Snowden as part of a continuing conspiracy designed to recruit more leakers.

Let me make clear from the onset: I am not endorsing this view, I am observing where I believe DOJ not only intends to head with this, but has already headed with it.

Using Snowden as a recruitment tool

After laying out how Chelsea Manning obtained and leaked files that were listed in the WikiLeaks Most Wanted list (the Iraq Rules of Engagement and Gitmo files, explicitly, and large databases more generally; here’s one version of the list as entered into evidence at Manning’s trial), then describing Assange’s links to LulzSec, the superseding Assange indictment lays out WikiLeaks’ overt post-leak ties and claimed ties to Edward Snowden.

83. In June 2013, media outlets reported that Edward J. Snowden had leaked numerous documents taken from the NSA and was located in Hong Kong. Later that month, an arrest warrant was issued in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, for the arrest of Snowden, on charges involving the theft of information from the United States government.

84. To encourage leakers and hackers to provide stolen materials to WikiLeaks in the future, ASSANGE and others at WikiLeaks openly displayed their attempts to assist Snowden in evading arrest.

85. In June 2013, a WikiLeaks association [Sarah Harrison, described as WLA-4 in the indictment] traveled with Snowden from Hong Kong to Moscow.

86. On December 31, 2013, at the annual conference of the Chaos Computer Club (“CCC”) in Germany, ASSANGE, [Jacob Appelbaum] and [Harrison] gave a presentation titled “Sysadmins of the World, Unite! A Call to Resistance.” On its website, the CCC promoted the presentation by writing, “[t]here has never been a higher demand for a politically-engaged hackerdom” and that ASSANGE and [Appelbaum] would “discuss what needs to be done if we re going to win.” ASSANGE told the audience that “the famous leaks that WikiLeaks has done or the recent Edward Snowden revelations” showed that “it was possible now for even a single system administrator to … not merely wreck[] or disabl[e] [organizations] … but rather shift[] information from an information apartheid system … into the knowledge commons.” ASSANGE exhorted the audience to join the CIA in order to steal and provide information to WikiLeaks, stating, “I’m not saying doing join the CIA; no, go and join the CIA. Go in there, go into the ballpark and get the ball and bring it out.”

87. At the same presentation, in responding to the audience’s question as to what they could do, [Appelbaum] said “Edward Snowden did not save himself. … Specifically for source protection [Harrison] took actions to protect [Snowden] … [i]f we can succeed in saving Edward Snowden’s life and to keep him free, then the next Edward Snowden will have that to look forward to. And if look also to what has happened to Chelsea Manning, we see additionally that Snowden has clearly learned….”

The following section describes how, “ASSANGE and WikiLeaks Continue to Recruit,” including two more paragraphs about the Most Wanted Leaks:

89. On May 15, 2015, WikiLeaks tweeted a request for nominations for the 2015 “Most Wanted Leaks” list, and as an example, linked to one of the posts of a “Most Wanted Leaks” list from 2009 that remained on WikiLeaks’s website.

[snip]

92. In June 2015, to continue to encourage individuals to hack into computers and/or illegaly obtain and disclose classified information to WikiLeaks, WikiLeaks maintained on its website a list of “The Most Wanted Leaks of 2009,” which stated that documents or materials nominated to the list must “[b]e likely to have political, diplomatic, ethical or historical impact on release … and be plausibly obtainable to a well-motivated insider or outsider,” and must be “described in enough detail so that … a visiting outsider not already familiar with the material or its subject matter may be able to quickly locate it, and will be motivated to do so.”

Effectively, Snowden is included in this indictment not because the government is alleging any ties between Snowden and WikiLeaks in advance of his leaks (Snowden’s own book lays out reasons to think there was more contact between him and Appelbaum than is publicly known, but the superseding Assange indictment makes no mention of any contacts before Snowden’s first publications), but because WikiLeaks used their success at helping Snowden to flee as a recruiting pitch.

Snowden admits Harrison got involved to optimize his fate

This is something that Snowden lays out in his book. First, he addresses insinuations that Assange only helped Snowden out of selfish reasons.

People have long ascribed selfish motives to Assange’s desire to give me aid, but I believe he was genuinely invested in one thing above all—helping me evade capture. That doing so involved tweaking the US government was just a bonus for him, an ancillary benefit, not the goal. It’s true that Assange can be self-interested and vain, moody, and even bullying—after a sharp disagreement just a month after our first, text-based conversation, I never communicated with him again—but he also sincerely conceives of himself as a fighter in a historic battle for the public’s right to know, a battle he will do anything to win. It’s for this reason that I regard it as too reductive to interpret his assistance as merely an instance of scheming or self-promotion. More important to him, I believe, was the opportunity to establish a counterexample to the case of the organization’s most famous source, US Army Private Chelsea Manning, whose thirty-five-year prison sentence was historically unprecedented and a monstrous deterrent to whistleblowers everywhere. Though I never was, and never would be, a source for Assange, my situation gave him a chance to right a wrong. There was nothing he could have done to save Manning, but he seemed, through Sarah, determined to do everything he could to save me.

This passage is written to suggest Snowden believed these things at the time, describing what “seemed” to be true at the time. But it’s impossible to separate it from Appelbaum’s explicit comparison of Manning and Snowden at CCC in December 2013.

Snowden then describes what he thinks Harrison’s motive was.

By her own account, she was motivated to support me out of loyalty to her conscience more than to the ideological demands of her employer. Certainly her politics seemed shaped less by Assange’s feral opposition to central power than by her own conviction that too much of what passed for contemporary journalism served government interests rather than challenged them.

Again, this is written to suggest Snowden believed it at the time, though it’s likely what he has come to believe since.

Then Snowden describes believing, at that time, that Harrison might ask for something in exchange for her help — some endorsement of WikiLeaks or something.

As we hurtled to the airport, as we checked in, as we cleared passport control for the first of what should have been three flights, I kept waiting for her to ask me for something—anything, even just for me to make a statement on Assange’s, or the organization’s, behalf. But she never did, although she did cheerfully share her opinion that I was a fool for trusting media conglomerates to fairly guard the gate between the public and the truth. For that instance of straight talk, and for many others, I’ll always admire Sarah’s honesty.

Finally, though, Snowden describes — once the plane entered into Chinese airspace and so narratively at a time when there was no escaping whatever fate WikiLeaks had helped him pursue — asking Harrison why she was helping. He describes that she provided a version of the story that WikiLeaks would offer that December in Germany: WikiLeaks needed to be able to provide a better outcome than the one that Manning suffered.

It was only once we’d entered Chinese airspace that I realized I wouldn’t be able to get any rest until I asked Sarah this question explicitly: “Why are you helping me?” She flattened out her voice, as if trying to tamp down her passions, and told me that she wanted me to have a better outcome. She never said better than what outcome or whose, and I could only take that answer as a sign of her discretion and respect.

Whatever has been filtered through time and (novelist-assisted) narrative, Snowden effectively says the same thing the superseding indictment does: Assange and Harrison went to great lengths to help Snowden get out of Hong Kong to make it easier to encourage others to leak or hack documents to share with WikiLeaks. I wouldn’t be surprised if these excerpts from Snowden’s book show up in any Assange trial, if it ever happens.

Snowden’s own attempt to optimize outcomes

Curiously, Snowden did not say anything in his book about his own efforts to optimize his outcome, which is probably the most interesting new information in Bart Gellman’s new book, Dark Mirror (the book is a useful summary of some of the most important Snowden disclosures and a chilling description of how aggressively he and Askhan Soltani were targeted by foreign governments as they were reporting the stories). WaPo included the incident in an excerpt, though the excerpt below is from the book.

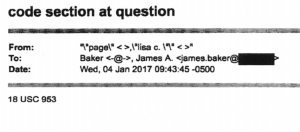

Early on in the process, Snowden had asked Gellman to publish the first PRISM document with a key, without specifying what key it was. When WaPo’s editors asked why Gellman’s source wanted them to publish a key, Gellman finally asked.

After meeting with the Post editors, I remembered that I could do an elementary check of the signature on my own. The result was disappointing. I was slow to grasp what it implied.

gpg –verify PRISM.pptx.sig PRISM.pptx

gpg: Signature made Mon May 20 14:31:57 2013 EDT

using RSA key ID ⬛⬛⬛⬛⬛⬛⬛⬛

gpg: Good signature from “Verax”

Now I knew that Snowden, using his Verax alter ego, had signed the PowerPoint file himself. If I published the signature, all it would prove to a tech-savvy few was that a pseudonymous source had vouched for his own leak. What good would that do anyone?

In the Saturday night email, Snowden spelled it out. He had chosen to risk his freedom, he wrote, but he was not resigned to life in prison or worse. He preferred to set an example for “an entire class of potential whistleblowers” who might follow his lead. Ordinary citizens would not take impossible risks. They had to have some hope for a happy ending.

To effect this, I intend to apply for asylum (preferably somewhere with strong Internet and press freedoms, e.g. Iceland, though the strength of the reaction will determine how choosy I can be). Given how tightly the U.S. surveils diplomatic outposts (I should know, I used to work in our U.N. spying shop), I cannot risk this until you have already gone to press, as it would immediately tip our hand. It would also be futile without proof of my claims—they’d have me committed—and I have no desire to provide raw source material to a foreign government. Post publication, the source document and cryptographic signature will allow me to immediately substantiate both the truth of my claim and the danger I am in without having to give anything up. . . . Give me the bottom line: when do you expect to go to print?

Alarm gave way to vertigo. I forced myself to reread the passage slowly. Snowden planned to seek the protection of a foreign government. He would canvass diplomatic posts on an island under Chinese sovereign control. He might not have very good choices. The signature’s purpose, its only purpose, was to help him through the gates.

How could I have missed this? Poitras and I did not need the signature to know who sent us the PRISM file. Snowden wanted to prove his role in the story to someone else. That thought had never occurred to me. Confidential sources, in my experience, did not implicate themselves—irrevocably, mathematically—in a classified leak. As soon as Snowden laid it out, the strategic logic was obvious. If we did as he asked, Snowden could demonstrate that our copy of the NSA document came from him. His plea for asylum would assert a “well-founded fear of being persecuted” for an act of political dissent. The U.S. government would maintain that Snowden’s actions were criminal, not political. Under international law each nation could make that judgment for itself. The fulcrum of Snowden’s entire plan was the signature file, a few hundred characters of cryptographic text, about the length of this paragraph. And I was the one he expected to place it online for his use.

Gellman, Poitras, and the Post recognized this would make them complicit in Snowden’s flight and go beyond any journalistic role.

After some advice from WaPo’s lawyers, Gellman made it clear to Snowden he could not publish the key (and would not have, in any case, because the slide deck included information on legitimate targets he and the WaPo had no intent of publishing).

We hated the replies we sent to Snowden on May 26. We had lawyered up and it showed. “You were clear with me and I want to be equally clear with you,” I wrote. “There are a number of unwarranted assumptions in your email. My intentions and objectives are purely journalistic, and I will not tie them or time them to any other goal.” I was working hard and intended to publish, but “I cannot give you the bottom line you want.”

This led Snowden to withdraw his offer of exclusivity which — as Gellman tells the story — is what led Snowden to renew his efforts to work with Glenn Greenwald. The aftermath of that decision led to a very interesting spat between Gellman and Greenwald — to read that, you should buy the book.

To be clear, I don’t blame Snowden for planning his first releases in such a way as to optimize the chances he wouldn’t spend the rest of his life in prison. But his silence on the topic in his own account, even while he adopted the WikiLeaks line about their goal of optimizing his outcome, raises questions about any link between Harrison’s plans and Snowden’s.

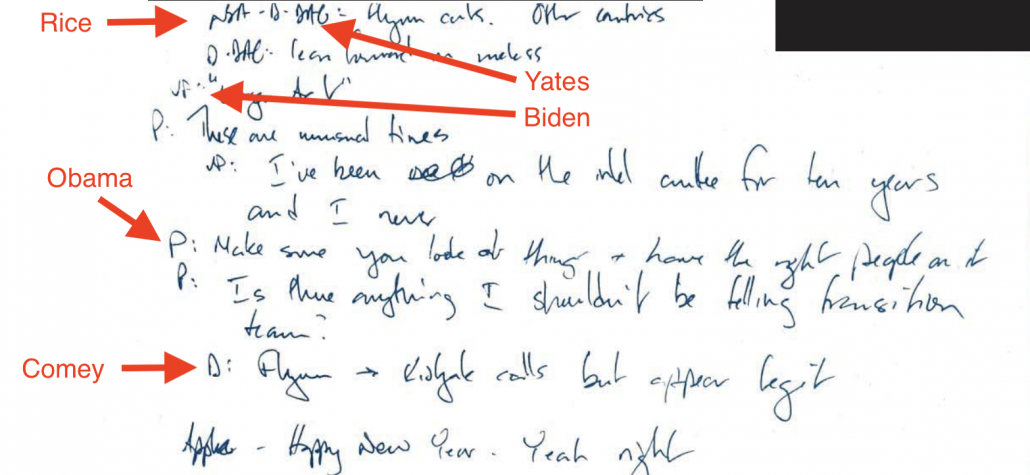

The government is using Snowden as inspiration in other cases

The superseding Assange indictment is the first place I know of where the government has specifically argued that WikiLeaks’ assistance to Snowden amounted to part of a criminal conspiracy (though it is totally unsurprising and I argued that it was clear the government was going there based on what they had argued in the Joshua Schulte case).

But it’s not the first place they have argued a tie between Snowden as inspiration and further leaks.

The indictment for Daniel Everette Hale, the guy accused of sharing documents on the drone program with Jeremy Scahill, makes it clear how Hale’s relationship with Scahill blossomed just as the Snowden leaks were coming out (and this detail makes it clear he’s the one referred to in Citizenfour as another source coming forward).

15. On or about June 9, 2013, the Reporter sent HALE an email with a link to an article about Edward Snowden in an online publication. That same day. Hale texted a friend that the previous night he had been hanging out with journalists who were focused on his story. Hale wrote that the evening’s events might provide him with “life long connections with people who publish work like this.”

Hale launched a fairly aggressive (and if it weren’t in EDVA, potentially an interesting) challenge to the Espionage Act charges against him. It included (but was not limited to) a Constitutional motion to dismiss as well as a motion to dismiss for selective prosecution. After his first motions, however, both the government’s response and Hale’s reply on selective prosecution were (and remain, nine months later) sealed.

But Hale’s reply on the Constitutional motion to dismiss was not sealed. In it, he makes reference to what remains sealed in the selective prosecution filings. That reference makes it clear that the government described searching for leakers who had been inspired “by a specific individual” who — given the mention of Snowden in Hale’s indictment — has to be Snowden.

Moreover, as argued in more detail in Defendant’s Reply in support of his Motion to Dismiss for Selective or Vindictive Prosecution (filed provisionally as classified), it appears that arbitrary enforcement – one of the risks of a vague criminal prohibition – is exactly what occurred here. Specifically, the FBI repeatedly characterized its investigation in this case as an attempt to identify leakers who had been “inspired” by a specific individual – one whose activity was designed to criticize the government by shedding light on perceived illegalities on the part of the Intelligence Community. In approximately the same timeframe, other leakers reportedly divulged classified information to make the government look good – by, for example, unlawfully divulging classified information about the search for Osama Bin Laden to the makers of the film Zero Dark Thirty, resulting in two separate Inspector General investigations.3 Yet the investigation in this case was not described as a search for leakers generally, or as a search for leakers who tried to glorify the work of the Intelligence Community. Rather, it was described as a search for those who disclosed classified information because they had been “inspired” to divulge improprieties in the intelligence community.

Hale argued, then, that the only reason he got prosecuted after some delay was because the FBI had a theory about Snowden’s role in inspiring further leaks.

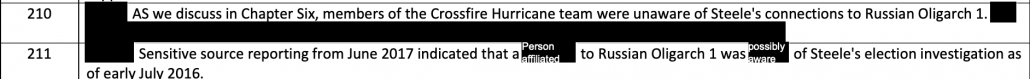

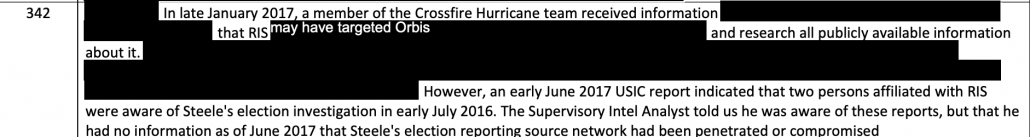

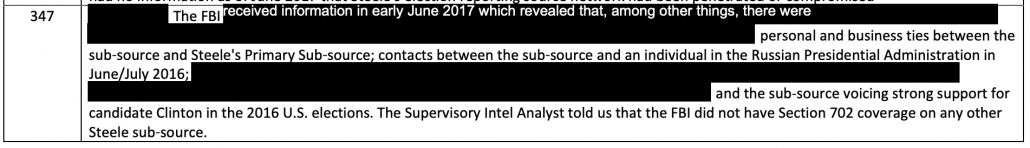

Judge Liam O’Grady denied both those motions (and most of Hale’s other motions), though without further reference to Snowden as an inspiration. But I’m fairly sure this is not the only case where they’re making this argument.