M&M Mars Candy, Trump and The Estate Tax Giveaway

[Ed Note: This is a guest post by our tax law expert friend Bob Lord. It is a particularized abject story of exactly what kind of interests are pushing the Trump “Tax Cuts” agenda, why, and how ridiculously corrupt and insulting to the 99.5% of America the effort really is.]

[Ed Note: This is a guest post by our tax law expert friend Bob Lord. It is a particularized abject story of exactly what kind of interests are pushing the Trump “Tax Cuts” agenda, why, and how ridiculously corrupt and insulting to the 99.5% of America the effort really is.]

The Mars family has made billions selling us M&Ms, Snickers, and countless other Halloween treats for a century now. But when it comes to paying tax, the Mars family seems to be all tricks and no treats.

In fact, the family’s latest tax trick may have cost the U.S. Treasury a whopping $10 billion. What could $10 billion do? That’s the cost of delivering prenatal care to hundreds of thousands of expectant moms under Medicaid, an essential program that President Trump and the GOP Congress plan to cut by up to $1 trillion.

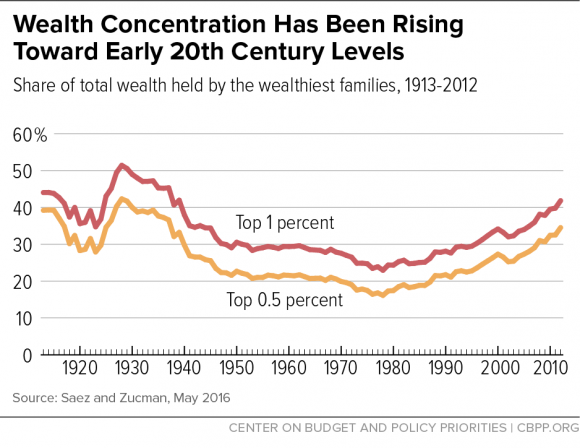

According to the current U.S. tax code, any American worth $25 billion can expect 40 percent of that, or $10 billion, to go to Uncle Sam in estate tax, the federal levy on the personal fortunes of deep pockets who kick the bucket. Forrest Mars Jr. had a $25-billion fortune when he died in July 2016. But the Mars family has apparently been able to avoid estate tax on that entire $25 billion.

How do we know? Researchers at Forbes and Bloomberg, the two business publications that track America’s billionaire wealth, have some fascinating numbers for us.

Forest Jr. and his two siblings started 2016 with personal fortunes in the vicinity of $25 billion. Now if Forrest’s fortune had been subject to a significant estate tax after he passed on, the collective wealth of his four daughters in 2017 would be substantially less than that $25 billion.

The just-released 2017 Forbes list of America’s 400 richest shows otherwise. Forbes puts the wealth of each of Forest’s four daughters at $6.3 billion, for a total of $25.2 billion. That’s almost identical to the 2017 fortunes of their Aunt Jacqueline and their Uncle John, each at $25.5 billion. The Bloomberg Billionaires Index reports similar numbers.

Should any of this surprise us? Not really. We’re seeing Mars family history repeat itself. Eighteen years ago, Forrest Mars Sr., the original Mars family billionaire, died. The Forbes 400 lists from the years surrounding 1999 show that the Mars family lost no wealth to estate tax back then either.

But the Mars family must at least be paying oodles of income tax, right? Nope. How could that be? This particular tax-avoidance story starts over a century ago, when Frank Mars incorporated his candy business.

Back then, the value of the stock in Mars Inc. had only minimal value. But over the years the stock appreciated considerably in value. By 1988, that appreciation had made the Mars family the wealthiest clan in America. The Mars billionaires still rank as one of America’s wealthiest families, in no small part because none of the gains in the value of the family’s Mars stock have ever been subject to income tax.

Is the Mars family content with its current level of tax savings? Apparently not. The family has joined with 17 other billionaire families and collectively spent $500 million lobbying Congress for reduced taxes on billionaires and the companies they run.

These companies face corporate income tax on their profits. Mars, Inc. has had to pay these taxes over the years. Unlike Mars family members as individuals, the Mars company hasn’t been able to sidestep its tax bills. But the Mars and other billionaire families have found a friend in President Trump and the current Republican-led Congress. The pending Trump-GOP tax plan would take a meat axe to corporate tax rates.

The resulting corporate tax savings, if this plan gets adopted, will likely translate into a multi-billion-dollar tax savings for Mars, Inc. — and a corresponding bump in the net worth of Mars family members.

The real prize for the Mars in the Trump tax plan? That may be in the elimination of the estate tax that the Trump White House is now pushing. Wait, what? How would the repeal of the federal estate tax help a family that’s already avoiding the estate tax?

For America’s ultra-wealthy, repealing the estate tax turns out to be more about the federal income than the federal estate tax. As Mars family history makes painfully clear, tax avoidance vehicles available under current law allow even billionaires to zero out their estate tax.

But billionaires, under current law, do pay an appreciable income tax price for their estate tax avoidance. Assets on which estate tax is avoided carry an offsetting income tax disadvantage. That disadvantage would vanish in a simple estate tax repeal.

What does that mean? Let’s say we have a billionaire who paid $10 million for stock now worth $100 million and does nothing to avoid estate tax on that stock The billionaire never has to pay income tax on that gain. Those who inherit that stock from the billionaire’s taxable estate can sell it for $100 million and not pay any income tax on the gain either.

But if that billionaire stashed that stock into a trust to avoid estate tax, he would forfeit that income tax advantage. The untaxed gain associated with the stock would be passed to the trust beneficiaries. These beneficiaries would face an income tax on the previously untaxed gain when they sell the stock.

If the Trump-GOP estate tax repeal takes the same final form as the estate tax repeal bill introduced in the House of Representatives in 2015, wealthy Americans will get to have it both ways: zero estate tax and the elimination of any untaxed gain at death.

And that would allow the next generation of Mars family members to avoid income tax on over a century’s worth of economic gain. Quite a trick, huh?

So enjoy the candy, America. The Mars family will keep the cash.

Happy Halloween!

[Robert J. Lord, a tax lawyer in Phoenix, Arizona and former Congressional candidate, is an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies.]

![[Photo: STIL via Unsplash]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Money_STIL-Unsplash_mod-1500x1000.jpg)

![[source: Google Finance]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Screenshot_GoogleFin-TrumpNK_09AUG2017-300x163.jpg)