[NB: Check the byline — it’s me, Rayne. I am not a registered financial representative or a lawyer; this post is based on my own observations and opinions. As always, your mileage may vary.]

On a chilly March evening ten years ago tonight, I was yelling at loved ones: Sell. For gods’ sake, SELL.

My own household had moved its investments from a number of mutual funds to guaranteed income. Every fund in the portfolio to that point contained a chunk of an investment bank and was therefore exposed to what I felt was sure to come.

It was obvious to anyone who was really paying attention that something was really off. Trying to buy a house in 2004 was almost impossible where I live, in spite of the ongoing migration of manufacturing jobs offshore. In the target price range for a 2000-square foot house, there were only a handful of homes listed and they all needed more than $50K in improvements. The nearby farmers’ fields were full of a new crop: single-family homes, mostly 3-bedroom and up, had eaten acres and acres in less than a year. It was insanity — there was no way this pace could be maintained, not with my state’s problematic over-reliance on the automobile industry.

Instead of buying an existing home, I built a new one. It didn’t make sense to spend $50K on improvements requiring a lot of construction if I couldn’t guarantee I could hire a contractor when new construction was so hot. I didn’t build in the top end neighborhood, either. I left myself some room in case I had to leave the area quickly for a new job; I also left room for the market to improve.

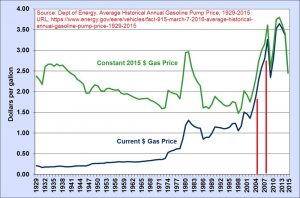

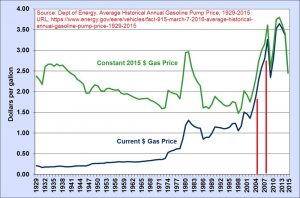

Except it didn’t. The last landscaping contractor must have pulled away from my new home in 2005 just as the bubble began to deflate. There were signs it was going to get worse, too, what with fuel prices skyrocketing. Banks increasingly offered crazy terms on mortgages just so they could something, anything, not taking the hint the market was saturated. Given the number of people relying too heavily on adjustable rate mortgages with ridiculously low entry rates, the increased gasoline price costing the average family more than $1000 a year was certain to cause credit card defaults and foreclosures.

Something ugly was coming.

~ ~ ~

In March 2008 — almost exactly a month after the Washington Post published an op-ed by New York’s then-Governor Eliot Spitzer exhorting action on subprime mortgages — 85-year-old American investment bank Bear Stearns crashed and burned.

After urgent, fancy foot work by the Federal Reserve Bank, J.P. Morgan and other key investors, settlements were made with bail out money and remnants of the firm were ultimately snapped up by J.P. Morgan for what amounted to the cost of Bear Stearn’s headquarters building, about $2 per share. By St. Patrick’s Day, Bear Stearns was no more, completely subsumed.

It would be another six months before the next large investment bank crashed — Lehman Brothers — taking the global economy with it.

~ ~ ~

At the time the crash was blamed on lax controls on lending to home buyers, encouraging an excess of subprime mortgages, combined with investment banks’ more recent taste for collateralized debt obligations bundling mortgages into tranches for slicing up and trading.

But not all of the trash loans were residential mortgages stuffed into tranches. Some of the loans were to developers and contractors who were building commercial facilities and multi-family buildings. Some of these loans were packaged into funds which were more like offshore corporations.

The two funds triggering Bear Stearns’ meltdown were just that: offshore funds incorporated in the Cayman Islands in 2003, holding various assets including tranches of poorly-collateralized mortgages, managed by Bear Stearns Asset Management (BSAM). What mortgages were in these two funds the public doesn’t really know; were they single-family residential mortgages or commercial facilities mortgages, or some combination? The information is out there somewhere but it’s not at the public’s fingertips.

The financial media still paints a messy picture even a decade later, blaming Bear Stearns management but not its own persistent failure to provide a more comprehensive and accessible picture of the financial industry’s health.

These two funds collapsed because too many mortgages within their CDOs failed; the effect on the bank was like pulling out two critical load-bearing pieces in a game of Jenga. The cascading demand for cash to resolve the failures may have pushed other investment banks’ equally sketchy funds to fail as well, crashing the entire heap nearly a decade ago.

~ ~ ~

It was a surprise blast from the unpleasant past to see Bear Stearns’ name pop up in the middle of recent testimony before the House Permanent Subcommittee on Intelligence. Fusion GPS’ Glenn Simpson cited the investment bank as a source of financing for Donald Trump and some sketchy condominium development.

[SIMPSON]… There’s the Trump vodka business that was earlier. And then ultimately, you know, what we came to realize was that the money was actually coming out of Russia and going into his properties in Florida and New York and Panama and Toronto and these other places.

And what we, you know, gradually begun to understand, which, you know, I suppose I should kick myself for not figuring out earlier, but I don’t know that much about the real estate business, which is I alluded to this earlier, so, you know, by 2003, 2004, Donald Trump was not able to get bank credit for — and if you’re a real estate developer and you can’t get bank loans, you know, you’ve got a problem.

And all these guys, they used leverage like, you know, — so there’s alternative systems of financing, and sometimes it’s — well, there’s a variety of alternative systems of financing. But in any case, you need alternative financing.

One of the things that we now know about how the condo projects were financed is that you have to — you can get credit if you can show that you’ve sold a certain number of units.

So it turns out that, you know, one of the most important things to look at is — this is especially true of the early overseas developments, like Toronto and Panama — you can get credit if you can show that you sold a certain percentage of your units.

And so the real trick is to get people who say they’ve bought those units, and that’s where the Russians are to be found, is in some of those pre-sales, is what they’re called. And that’s how, for instance, in Panama they got the credit of — they got a — Bear Stearns to issue a bond by telling Bear Stearns that they’d sold a bunch of units to a bunch of Russian gangsters.

And, of course, they didn’t put that in the underwriting information, they just said, we’ve sold a bunch of units and here’s who bought them, and that’s how they got the credit. So that’s sort of an example of the alternative financing. … [bold mine, excerpt pages 95-96]

The timing mentioned, 2003-2004, is very close to the time that Bear Stearns launched the two Cayman-based funds which failed first. Is it possible Trump’s financing provided by Bear Stearns ended up in the funds’ CDOs? Probably not — Simpson refers to bonds. But let’s look at a financial statement from one of the subject funds:

It’s difficult to tell what’s in any of the CDOs listed in this summary. Who knows what mortgages are in them or from where they originated without access to more details?

Note the bonds at the bottom — again, what’s in them? What percentage of these bonds consisted of dicey or outright fraudulent financing for construction related to money laundering? Again, we can’t tell without access to more granular details. We don’t know whether bond(s) offered to Trump developments were in Bear Stearns’ first two failed funds or if they helped cause the eventual financial pyroclastic flow toward Bear Stearns’ end.

~ ~ ~

Another thing sticks in my craw — a bit from Michael Lewis’ The Big Short:

The bond market, because it consisted mainly of big institutional investors, experienced no similarly populist political pressure. Even as it came to dwarf the stock market, the bond market eluded serious regulation. Bond salesmen could say and do anything without fear that they’d be reported to some authority. Bond traders could explore inside information without worrying that they would be caught. Bond technicians could dream up ever more complicated securities without worrying too much about government regulation — one reason why so many derivatives had been derived, one way or another, from bonds. … [bold mine]

In other words, nobody would look askance at all at bonds sold to finance a condominium development with rather thin commitment to payment. Nobody looked askance at the ratio of CDOs to bonds, either, though Bear Stearns would try to offset the CDOs’ losses by liquidating bonds. This fund as an example couldn’t manage this offset based on the ratio alone; it would have been catastrophically worse if the collateral beneath the bonds was as fraudulent as many subprime adjustable rate mortgages in CDOs were at the time.

The root cause of the 2008 crash remains the collapse of poorly collateralized as well as fraudulent mortgages. But I have to wonder:

— With so much attention on CDOs and mortgage defaults combined with a lack of bond market adequate monitoring, how much did crappy bonds, based on fraudulent representations of collateral, contribute to the crash?

— If there was so little regulation and oversight of the bond market, how much sketchy or fraudulent project financing was in bonds on the banks’ books — including projects like Trump’s, based on promises to pay made by offshore vehicles or non-U.S. citizens?

— With so little regulation and oversight, would it have been possible for one or more nation-states using offshore finance vehicles to “weaponize” banks’ books? How many of the crappy bonds contributing to the 2008 crash were based on poorly collateralized pre-sales to Russian oligarchs and gangsters?

— What assurances do we have today — especially with Mick Mulvaney defunding the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau and knocking off an opportunity to look more deeply into credit reporting by killing off the Equifax investigation — that investment banks have changed their practices and ensured legitimate projects are financed?

—What assurances do we have that our legislators see the slippery slip when they approve legislation like S. 2155 just this week, weakening Dodd-Frank reforms?

~ ~ ~

Recall the state of the economy between Bear Stearns’ and Lehman Brothers’ crashes. Oil prices rose to over $150/barrel, resulting in $4/gallon gasoline. Other commodity prices rose in tandem with fuel prices. The home buyers who could least afford any change in their household expenses were the same ones targeted for subprime mortgages with shady terms; it came down to paying for gas to get to work and feeding the family, or making the mortgage payment.

The price of oil at the time had been driven up by excess speculation. Legislation passed in June 2008 requiring all commodity futures trading to require a minimum of 30% margin upfront rather than 10%. Oil prices dropped drastically and reduced in volatility almost overnight, but it was already too late. Too many home buyers could no longer afford their payments and mortgage defaults began to snowball.

Which brings me to yet another question: if the bond market could have been “weaponized” at that time, could a volatile commodities market likewise have been used as a trigger?

Are there any other weak points in our market which could be “weaponized,” for that matter?

~ ~ ~

On this tenth anniversary after the crash began with Bear Stearns’ collapse, I feel more secure about my retirement portfolio. There were no frantic phone calls to family members exhorting moves to safety this evening. My exposure to the remaining weaknesses of investment banking have been minimized as much as possible, though I remain vulnerable because I have a mortgage. Real estate isn’t the sure return it once was. Only uber-wealthy investors buying into certain urban markets come out on top. But wealthy real estate investors can still cause self-inflicted damage.

Atlanta, Georgia’s market has turned around since the crash — but it was home to another failed Trump real estate project, a 363-unit Trump Tower which went into foreclosure with pre-sales of only 100 units. (In January 2017, Trump ranted about Atlanta as Rep. John Lewis’ district, calling it “falling apart” and “crime infested.” One wonders what crime he meant…)

Hollywood, Florida had a brush with a failed Trump project:

In 2006, he and billionaire condo king Jorge Perez began selling a 23-story apartment building near Mar-a-Lago, but the project was abandoned a year later because of slow sales. Another Perez-Trump deal, the 200-unit Hollywood oceanfront tower, was foreclosed in 2010 after selling less than 15% of its units. (The building eventually opened, still Trump-branded, but without Perez.)

So did the Miami, Florida area:

Trump Sunny Isles, a three-tower residential complex outside Miami, has also struggled. Trump partnered with Perez again and another developer named Gil Dezer to build the project, which targeted wealthy Latin Americans. . . .

Unfortunately, the last two towers of the development opened in the middle of the financial crisis, and Perez bailed on them. . . .

And Puerto Rico, too, was home to a Trump-branded golf course which failed in 2015.

Though with so many failures followed by continued attempts, it’s worth asking if this is a business model. How does Trump continue to benefit from so much failure? How do the backers he has benefit from staking Trump money or title?

Trump’s business alone wasn’t the cause of the 2008 crash. There were far more players involved — millions, if we want to blame residential homeowners who were misled by banks to believe they could safely contract a mortgage in spite of either inadequate collateral or income and ultimately forced into foreclosure. But at least one of Trump’s business projects was in the mix if Fusion’s Simpson’s testimony is truthful; what would keep Trump or real estate investors like Trump from contributing to (if not causing) another crash today?

We must ask when we see that Trump’s former campaign manager Paul Manafort and his former son-in-law Jeffrey Yohai were engaged in sketchy real estate development projects the community/regional Banc of California may have deterred by forcibly shutting their accounts.

And ask again when we see a community bank like The Federal Savings Bank of Chicago involved in another of Manafort’s bank frauds.

The damage could be even worse, in the case of Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, who is over his head in debt on 666 Fifth Avenue and whose family business is distressed, possibly causing geopolitical turmoil to shakedown new financing.

How many of these flimsy real estate deals and junky mortgages, loans, and bonds are there in the system when we can now see these affiliated with the president and his campaign advisers? How many of them will it take to cause another crash if legislators continue to pick away at safeguards?

Let’s hope I’m not writing another financial postmortem like this one in March 2028.

![[Photo: Annie Spratt via Unsplash]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Books_AnnieSpratt-Unsplash_mod1.jpg)