Trash Talk: NCAA Shame, Ephs and Jeffs

Marcy is correct, the article this week in the Atlantic magazine by Taylor Branch is an absolute must read. Entitled The Shame of College Sports, the article opens with a 2001 investigatory hearing in front of the Knight commission, a NCAA oversight board where slimy promoter Sonny Vaccaro matter of factly tells the Commission exactly what is going on in their sport; the Commission is incredulous, in denial and clearly thinks Vaccaro is scum. The reverse is, of course, the truth.

The list of scandals goes on. With each revelation, there is much wringing of hands. Critics scold schools for breaking faith with their educational mission, and for failing to enforce the sanctity of “amateurism.” Sportswriters denounce the NCAA for both tyranny and impotence in its quest to “clean up” college sports. Observers on all sides express jumbled emotions about youth and innocence, venting against professional mores or greedy amateurs.

For all the outrage, the real scandal is not that students are getting illegally paid or recruited, it’s that two of the noble principles on which the NCAA justifies its existence—“amateurism” and the “student-athlete”—are cynical hoaxes, legalistic confections propagated by the universities so they can exploit the skills and fame of young athletes. The tragedy at the heart of college sports is not that some college athletes are getting paid, but that more of them are not.

It is a long article that stretches in time from the beginning of college football in the late 1800s through the Cam Newton sham “investigation and disposition” prior to last season’s BCS Championship game. Coming on the heels of the stunning article on the corruption surrounding the Miami Hurricanes football program, it is a pretty stark reminder of just how filthy big time college athletics really are.

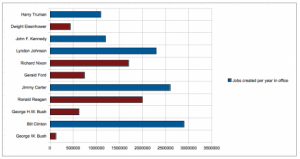

Many people have taken to advocating that college athletes be paid – above and beyond their scholarship terms – for their “services”. College basketball analyst Jay Bilas rants about doing so near daily in his Twitter stream. Personally, I am not sure that is the solution either. Do athletes at USC and Notre Dame get paid more because their brands bring in more? How much do each athlete get paid? Does Andrew Luck get paid a lot more than his left tackle? What about the universities not in say the top 64 programs, whose programs may not even be profitable, what do they do? What about basketball, baseball and track athletes? What about the girls and Title IX? I don’t know what the answer is, but I don’t like this one.

Interestingly enough, two of the most notoriously dirty major programs square off today when the Ohio State Felons take on the Miami Hurriconvicts in Miami. Nearly ten years ago, these two teams played for the National Championship (which Ohio State, true to their criminal form, stole from the Hurricanes on a horrid no-call on interference in the end zone in the last seconds). Now it is just another game. If only they could both lose.

To try to find a ray of clean and hope in this sick muck, let’s talk about teams that still play for the love of the game and the sport. Or so I am told. That’s right, I’m talking Ephs and Jeffs! The Williams Ephs open their 2011 season today at the always tough Bowdoin at Whiitier Field. While bitter arch rival, the Amherst Jeffs, open their season on the road against the fierce Bates Bobcats. Man, the stories we could tell about these games. Hopefully Marcy, Neil and/or Adam Bonin will come along and tell those stories cause, well you know, the ASU Sun Devils didn’t ever play those guys, I got nuthin!

In other games of note, Boise State already just tore up Toledo last night, and don’t be fooled, Toledo is a pretty good team. The BCS needs to get their heads out of their asses and give Boise some love. And Kellen Moore is simply amazing. The one truly huge game this weekend is Oklahoma down in Seminole land to take on Florida State. Oklahoma is, as befitting the number one ranked team, the favorite; but I dunno, I think FSU may be a sleeper here and, if their QB picks up where Christian Ponder left off, will win. I am agains personally interested in seeing Arizona State, who travel to Illinois. Been quite a while since ASU has been able to withstand prosperity, so being ranked at number 22 is a little scary. If Brock Osweiler has another big game, they should be okay, but the running game is not that good right now.

As to the pros, well the Deetroit Lions are the story of the year! The Kitties get KC, who got their asses kicked last week, at home in Ford Stadium. Look for Deetroit to go 2-0! Bears and Saint and Pats versus Bolts are the only other real excitement this week. I am going to let Marcy and Randiego battle that preview out in comments.

SPECIAL UPDATE!! – Uh, it turns out we gots some restless natives in these here parts, and they been demanding extra coverage. In another CRITICAL game, likely rivaled in scope only by the epic Cowboys/49ers tilt, Colt McCoy and the Cleveland Brownies are on the road at the Colts, and the Brownies are road favorites by 3. Wow. I must say, however, the fate of this game lies with Peyton. Peyton Hillis that is;the other one ain’t walking through that door. Oh, and speaking of Deetroit, Rosalind is right, the Tigers clinched their division yesterday. Congratulations, you gotta love Jim Leyland and Justin Verlander, who may yet be the first 25 game winner in MLB in decades (since Bob Welch).

Find more Jo Jo Gunne songs at Myspace Music