Mankiw’s Principles of Economics Part 8: A Country’s Standard of Living Depends on Its Ability to Produce Goods and Services

The introduction to this series is here.

Part 1 is here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

Part 4 is here.

Part 5 is here.

Part 6 is here.

Part 7 is here.

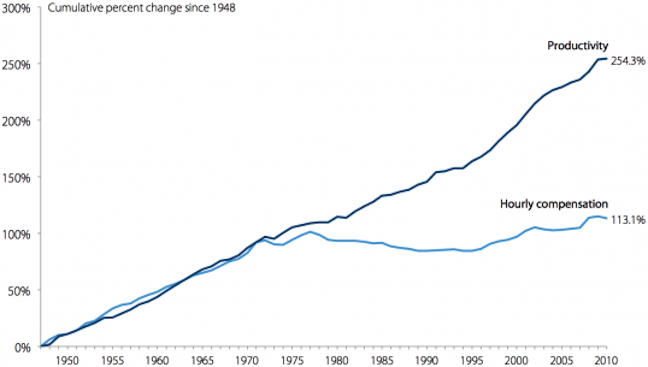

Mankiw’s eighth principle of economics is: a country’s standard of living depends on its ability to produce goods and services. He points out that there are vast differences between the average incomes of different countries. In the US, average income has increased about 2% per year adjusted for increases in the cost of living, he says, and doubles about every 35 years. The explanation for this change is productivity, defined as “the amount of goods and services produced from each unit of labor time.” The growth rate of a nation’s productivity determines the growth rate of its average income, he asserts. He dismisses other explanations, such as the prevalence of labor unions and minimum wage laws. He claims that US productivity dropped in the 1970s which accounts for the slow growth of average wages over that period. He concludes with this claim:

To boost living standards, policymakers need to raise productivity by ensuring that workers are well-educated, have the tools needed to produce goods and services, and have access to the best available technology.

This principle supports Philip Mirowski’s Sixth Commandment of Neoliberalism: Thou Shalt Become the Manager of Thyself. “Human beings [are reduced] to an arbitrary bundle of “investments,” skill sets, temporary alliances (family, sex, race), and fungible body parts.” The goal of the entrepreneur of you is to find some way to make yourself valuable enough to fill a slot in some corporate entity that will pay off on your investments. It also supports the Ninth Commandment, Thou Shalt Know that Inequality is Natural, because it tells the entrepreneur of you that if you fail, it’s your fault for being insufficiently productive. The problem is always the workers; and never the owners of capital for they can do no wrong. That comes from the Tenth Commandment, Thou Shalt Not Blame Corporations and Monopolies, especially for investing their capital in foreign countries so jobs are created there instead of in the US. After all, the free flow of capital is critical in Capitalism, as we learn in Mirowski’s discussion of Commandment 8: Thou Shalt Keep Thy Cronyism Cosmopolitan.

Mankiw’s explanation is intellectually dishonest. He only talks about average incomes, not median incomes, and not the incomes of the working people of the US. That enables him to paint a false picture of the economy, and of the role of productivity in increasing standards of living. The leading work on this issue was done by Larry Mishel at the Economic Policy Institute. His April 2012 paper, The Wedges Between Productivity And Median Compensation Growth is the seminal work on this issue. Here’s an updated chart showing the disparity between wages and productivity. For a discussion of the productivity measurement, see this 2014 Bureau of Labor Statistics paper. It’s important to note that Mishel is using the median wage growth for production/non-supervisory workers, not total labor compensation. With this statistic, we look at the actual experience of approximately 80% of workers.

According to Mishel, the gap in the chart from 2000 to 2011 is the result of three factors (see Table 1):

1. Income inequality increased, with the great gains going to the top few percentiles and the rest stagnant or falling, accounting for 39% of the gap.

2. Income shifted from labor to capital, accounting for 45% of the gap.

3. Output prices diverged from consumer prices, accounting for 16% of the gap.

Dave Dayen discusses Mishel’s paper here, focusing on efforts of conservatives to discredit Mishel’s work. The only consideration that seems even questionable is 3, and Dayen’s discussion seems fair. He concludes with this:

If you believe the Lawrence/Yglesias argument, policies that raise wages are secondary to policies that raise productivity more generally. If you believe the Mishel argument, reconnecting wages to productivity becomes central. Rather than stressing the need to acquire more education and skills, you would support increasing the minimum wage and allowing for more union organizing to put leverage in the hands of labor over capital. You would support proper use of overtime laws to reduce wage theft, and paid family and medical leave to keep wages strong during times of family stress.

But if productivity gains just leak out to the wealthy through financial engineering, all the growth in the world won’t benefit the typical worker.

Mankiw doesn’t acknowledge the problems with his principle, problems which have been evident for a long time as the chart shows. The source of this principle is the neoclassical argument of William Stanley Jevons and John Bates Clark which I discuss in detail here and here. Mankiw is preaching from the Natural Law Bible without mentioning it. This is a perfect example of Keynes’ dismissive statement on these writers: “We have not read these authors; we should consider their arguments preposterous if they were to fall into our hands.“ Certainly this principle is preposterous both factually and theoretically.

![[graphic: WSJ.com's July 8th error message]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/WSJ_504Msg_08JUL2015-300x127.jpg)